A hub for Iraqi refugees, San Diego is making way for new faces — this time from Syria

- Share via

Reporting from El Cajon, Calif. — The scent of black tea and rice wafts through the bare apartment the Zarour family has come to call home after fleeing Syria.

It’s been three months since they arrived in El Cajon, home to the second-largest Iraqi diaspora in the United States. Rasha Zarour wraps each grain of rice into the grape leaf in her palm as she prepares yebra, a traditional Syrian dish, for her children before they return from school.

Starting a new life has been difficult, she says, but it is better than the alternative they escaped four years ago: the crack of strafing fire from government or rebel troops in what was once the city of Homs, and explosions that left only gaping craters or rubble where bustling urban life once hummed.

“Everything is new,” she says.

Zarour, her husband and her five children are among the nearly 800 Syrian refugees who arrived in San Diego County last year and settled in El Cajon. California led the nation in resettlement of Syrian refugees in fiscal 2016, taking in 1,450 immigrants, according to the Pew Research Center.

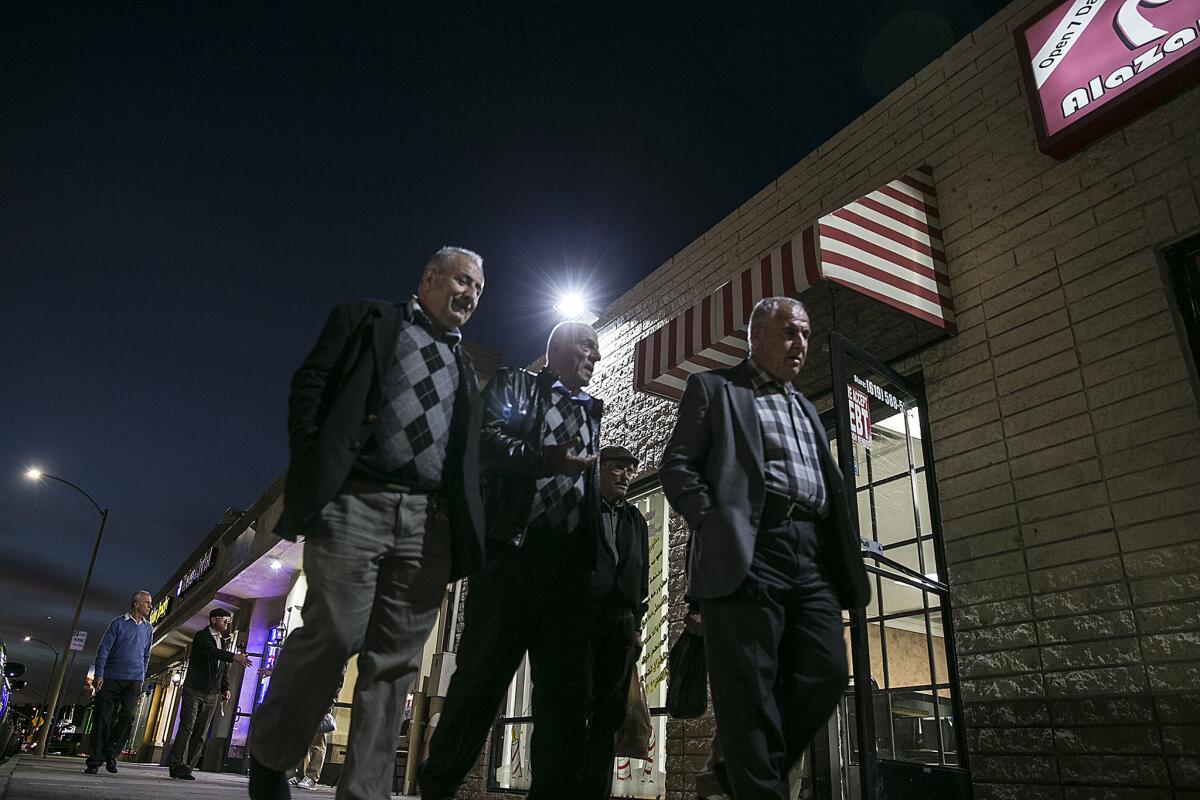

Iraqis have immigrated to San Diego for the last 30 years, many of them fleeing war and religious persecution in their motherland. More than 60,000 Chaldeans, or Iraqi Christians, live in El Cajon. Resettlement agencies see El Cajon, with its existing network of resources and community services in Arabic, as a prime location for refugees who don’t have family in the United States.

“The schools have Arabic-speaking staff to help the clients,” says Etleva Bejko, director of refugee and immigration services at Jewish Family Service, which helps resettle refugees. “The healthcare providers have the language skills to treat patients.”

Here, grocery store signs are in English and Arabic. Posters advertise realty and investment services in both languages, alongside signs for concerts headlined by Arab pop stars.

At the downtown El Cajon farmers market, resettlement agencies set up booths to explain their services and hand out ACLU pamphlets about the right to wear a hijab. Iraqi vendors work one table over, selling cilantro, turnips and herbs from a community garden maintained by immigrants and refugees. A sign hanging from their tent in Arabic asks shoppers not to haggle over vegetable prices.

“The community is there to support newcomers,” Bejko says. “It makes sense that quite a few Syrian refugees are here.”

The stress of starting anew has been amplified in recent weeks by President Trump’s executive order that placed a 120-day ban on all refugee admissions and an indefinite suspension of admission for Syrian refugees.

The travel ban is on pause after a federal judge in Seattle issued a temporary restraining order, but Zarour’s husband, Ahmad, who still has family in Jordan and Syria, wonders whether the order will affect them.

“Why does he view us as terrorists? We are people looking to start a new life,” he says of Trump. “We aren’t like that. We are Muslims, but we are very kind.”

Syrian refugees are flooding resettlement agencies with questions about the order, according to David Murphy, executive director of the International Rescue Committee’s San Diego chapter. The IRC is one of four resettlement agencies working with refugees in San Diego.

“Our phone lines are jammed up. People are asking, ‘What is going to happen to me?’” Murphy says. “Unfortunately, I can’t give them good answers. We are going literally day by day. Refugees traveling today know there can be problems along the way.”

The move from Dara to San Diego wasn’t a smooth transition for Rana Al Kard’s family. They had lived in a village in the southwestern city where the streets were lined with the homes of people they knew. Their entire family lived on the same road.

But Dara, like the city of Aleppo, has long been divided between Syrian government and opposition forces. One of Al Kard’s sons was killed in the conflict and another was injured when a sniper opened fire on her husband’s truck. Her surviving son, Mohamad, lives with a tube in his throat that allows him to breathe.

Community organizations that aid Syrian refugees says many have someone in their family who requires special medical care. Some come with nutritional problems; others arrive paralyzed from the war or are battling post-traumatic stress disorder.

Al Kard says she is grateful to be in California, where doctors can help her son recover. Her seven children, she says, are also happy to be the in U.S. because they look forward to going to school here and pursuing their dreams.

“It is a great gift for us,” Al Kard, 38, says in Arabic.

Unlike her husband, Khaled, and daughter Noor, Al Kard does not have to attend the mandatory workshops and English classes required of adult refugees. The resettlement agency allowed her to stay home because she has to care for Mohamad and her four other children who are still in school.

Our phone lines are jammed up. People are asking, ‘What is going to happen to me?’

— David Murphy, executive director of the IRC in San Diego

The family lives in a three-bedroom apartment about 15 minutes from El Cajon but hopes to move there for the Arabic-speaking community and lower rent. Noor Al Kard rides the bus to take English classes there and has already made new friends since arriving in November.

“I feel safe being around my friends there and being able to speak the language around people like me,” the 22-year-old says.

She appreciates being part of a community that readily accepts and understands her, she says. Without that kind of support, she would “go to workshops and come right back home.”

“Now, I’m encouraged to go there and spend time,” she says. “I can go to the Arabic market and walk around and discover the area.”

But Al Kard’s husband struggles with the move, she says. Noor nodded in agreement as she poured small cups of thick Syrian coffee for the family.

“I’m so happy to be here, but I see my husband and I can’t even tell him I’m happy,” Al Kard says.

In the evenings, when she tries to make snacks for the kids, her husband seems resentful of her joy, she says. He hopes to return to Jordan or Syria, where his siblings still live.

“He feels a different pressure to provide for the family,” she says.

Only two other Syrian families live in the apartment complex. One of them, Nabiha Andani, stopped by for a visit on a weekday afternoon. Her two daughters play with Al Kard’s children and they often drink coffee and eat breakfast together in the mornings. When Al Kard caught a cold a few weeks ago, Andani took her to the clinic and watched over her at home. It’s a friendship that would not have existed in Syria — the pair lived six hours apart.

Andani says she cried for four days when she heard of Trump’s executive order. Syrian President Bashar Assad forced her family to leave, she says, but Trump is no better if he tries to force them back to a place where they face death.

“When I came to the U.S., I thought I came to freedom,” she says as an interpreter translates. “Our freedom is being taken away again.”

Andani worries that her plans to secure a green card and help her family move to America have been destroyed. Under a ban, they wouldn’t be able to visit, either.

“Who will take care of them now?” she asked.

Two years after the Syrian civil war began, Zarour abandoned his small supermarket in Homs and gave up his work molding custom ceilings. The family settled in Damascus before it too became too dangerous. They fled to Zaatari refugee camp, a squalid but sprawling outpost near the Jordanian-Syrian border. They spent 20 days in the camp before they moved to another town.

Zarour could not work legally. He found odd jobs, accepting pay that was barely enough to feed his children.

“If the government knew I was working, they would arrest me,” Zarour says, speaking through an interpreter.

Early in their stay in Jordan, they registered as refugees with the United Nations. Eventually, after two years of interviews, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees referred them for resettlement in the United States.

When they finally arrived in California last November, the family moved into a motel in El Cajon. Finding an apartment was difficult because of a housing shortage, Zarour says. The family lived in the motel for 17 days.

Adjusting to a new life in America has bruised the pride of a man accustomed to providing for his family.

He struggles to learn the skills taught in workshops mandated by resettlement agencies — basics such as learning English, navigating public transportation or how to open a bank account. Attending those classes is tied to the financial aid the family receives.

To fit all seven people in their small two-bedroom apartment, the five children sleep wall-to-wall in the master bedroom. He and his wife sleep in the spare room.

The three couches in his living room were donated.

Before the war in Syria, he had a home of his own, lived near his siblings and held a government job that helped him pay the bills. As he places a glass of tea on the cardboard box he now uses as a coffee table, Zarour wonders if he will ever find a piece of the happiness he once knew.

Follow me on Twitter: @sarahparvini

MORE WORLD NEWS

Pakistan launches military crackdown as death toll in shrine bombing rises to 88

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.