Mother’s killing drives daughter’s quest for answers

The strangling of Alison Galvani’s mother was never solved. She hopes to persuade prosecutors to file charges — against her father.

- Share via

When Alison Galvani graduated from kindergarten in the summer of 1982, her mother took her to the musical "Annie" to celebrate. Then they went to Golden Gate Park for a picnic, spreading out a sleeping bag with white and yellow egrets on a green background. Alison played with her "Annie" doll.

Her mother, Nancy, had just filed for divorce, and she and Alison had moved into a residential hotel in San Francisco's seedy Tenderloin. Alison's father, Patrick, remained in the family's Victorian in Pacific Heights, one of the city's priciest neighborhoods.

Days after the picnic, fishermen found Nancy's body floating in San Francisco Bay. She had been strangled and was wearing only underpants. Her killer had bound her ankles and stuffed her into a sleeping bag, tying it with rope and weighting it with a cinder block.

Alison was 5. She remembers being with her father after her mother disappeared and waiting for her return. She ran to the window every time she heard a car. She remembers the arrival of police officers. They swarmed the house.

She said she was shown a photograph of the sleeping bag that shrouded her mother's body. It was the one she and her mother had used for the picnic, sprinkled with yellow and white egrets. It looked wet.

Alison said she remembers peering through a window and seeing her father handcuffed in the street and put into a police car.

Then her father returned home and took her to Pier 39 to ride the carousel. She said she felt relieved, and told him how much she loved him.

Alison, now 37, said she had fleeting suspicions about her father as she grew older.

At her wedding, something made her ask him to walk in front of her up the aisle. She didn't want to have to touch him, but she didn't understand her revulsion.

In 2008, her father came to visit in Connecticut, where she teaches epidemiology at Yale University. She was a new mother, and parenthood made her yearn for her own mother and identify with her.

When her father held her infant daughter, she felt nauseated. She started an argument with him, ostensibly about waking the baby.

Then, she said, she blurted out: "You killed my mother."

Nancy, a social worker, and Patrick, a computer programmer, had met in New York, married and eventually settled in San Francisco. Both came from well-educated, upper-middle-class families, and Alison was their only child.

Two months before her murder, Nancy, 36, applied for a restraining order against her husband, accusing him of punching her and holding a pillow over her face. She told others he had tried to kill her, and feared he would succeed if she got custody of Alison, according to a private investigator's report prepared for Alison and an interview with one of the witnesses.

Alison Galvani has a collection of photographs taken of her with her mother Nancy. More photos

Patrick Galvani, who was three years older than his wife, opposed the divorce. He said in court records that Nancy was paranoid. She had been diagnosed with manic depression, but lithium stabilized her.

"I believe her current fears of me are related to her mental illness," Patrick said in a court declaration.

He admitted in the declaration that he had held a pillow over Nancy's face during a fight, but said he did it to quiet her screams and "deaden the noise for the neighbor."

On Sunday, Aug. 8, 1982, Nancy was at the residential hotel preparing a communal dinner with her fellow tenants. Alison had gone to her father's for the weekend.

Nancy told her friends that she was supposed to pick up Alison on Monday morning, but her husband had called and moved up the time, witnesses told the police. He wanted her to get Alison on Sunday night.

Nancy was annoyed. In the last entry of her journal, which The Times examined, she mentioned Patrick's call and said he had refused to drop off Alison.

My father used me as bait to lure my mother to her death."— Alison Galvani

Michael Hurysz, who lived in the hotel at the time, was in the lobby when Nancy left. "She said, 'I will be right back. I am going to pick up Alison from her father,'" Hurysz said in a Times interview.

Nancy never returned. Her body was discovered the next day. Police found her yellow Buick in the garage of the Victorian where Patrick still lived.

He was arrested and formally charged with the murder. But prosecutors decided to drop the charges. San Mateo County Dist. Atty. Keith Sorenson, who has since died, told a newspaper that prosecutors concluded they had less than a 50% chance of winning a conviction. "I am not saying for a minute that he is innocent or didn't do it," Sorenson was quoted as saying to the San Francisco Examiner in 1982.

No witness had seen Patrick with his wife the night of the murder, and the case was "terribly circumstantial," said retired San Mateo County Deputy Dist. Atty. Al Giannini, who reviewed the evidence years later. A retired detective who worked on the case told The Times that some of the physical evidence had also been accidentally destroyed.

Patrick, now 70, did not respond to several attempts to reach him. John Keker, his lawyer, told the Examiner at the time that Patrick had passed a lie-detector test and wanted to help police find the true murderer.

Alison opened a door to her office building in New Haven and ushered a reporter upstairs to her office. She is small and slender, with dark hair worn in a braid and frameless oval glasses. Her voice is girlish and her manner intense.

Alison Galvani keeps a doll her mother gave her when she was a child. In her daughter's bedroom, a quilt her mother made hangs on the wall. More photos

At Yale, she has published more than 100 scientific articles and won a Guggenheim Fellowship. She has also evaluated vaccination strategies and antiviral therapies for the Centers for Disease Control and the World Health Organization, receiving international recognition and obtaining tenure at 33.

She said she's tormented by her suspicion that she might have played a role in her mother's murder. "My father used me as bait to lure my mother to her death," she said, a line she repeated often during the course of several interviews.

She and her husband and their three young children live in a rambling, toy-and-book-filled house not far from Yale. A quilt her mother made hangs in her daughter's bedroom. She has her mother's old green bathrobe and in the winter wears her mother's black wool coat.

There are no photographs of her father.

After her mother's death, Alison became her father's companion. She loved that he treated her as an adult, talking to her about politics and real estate during their nightly dinners at restaurants. She called him "Pat" instead of Daddy. They traveled to Europe and the Far East, and she attended San Francisco's toniest private schools. He said he wanted her to go to Harvard University.

"He told me I was his whole world," she said.

They rarely had adult visitors, and she saw her extended family only occasionally. Her mother had been an only child, and her maternal grandmother lived in Texas.

Alison said her messiness or whining could send her father into a rage. She said he once broke down her bedroom door and, on another occasion, gave her a black eye. "He would hit me all over, break things and throw things at me," she said in an interview. Afterward, she said, he would apologize and describe the incidents as "spanking."

Alison was 11 when her father decided to send her to a boarding school in England. He said the school would help her get into the University of Oxford, which he had decided was preferable to Harvard; she later would get her doctorate there. She begged him not to send her away, and he promised to follow her to England a year later.

He didn't follow her, but he arranged for her to come back to San Francisco for holidays and summers. During one of those visits, Amy Harrington, her closest friend in San Francisco, broached the subject of the murder. Amy confided that her own mother suspected that Alison's father had committed the crime.

It was the first time anyone had suggested that to Alison. She insisted it was not true.

"I almost fell out with Amy over her saying that," Alison said.

Harrington, now a lawyer, said, "Alison really loved her dad."

"My mother's vindication is that she has a daughter who loved her enough to try as hard as I did to get justice," Alison Galvani says. "My father lost that love, and that is his punishment." More photos

The turning point for Alison came after she accused her father of murdering her mother. His denial struck her as odd, she said. "He said, 'It wasn't my fault.'"

She called the Foster City Police Department, a small, San Mateo County agency that took charge of the murder probe because the body had been found in its jurisdiction. A detective called Alison back and asked if she would be willing to cooperate in an investigation into her father. She hesitated.

"My first reaction was protectiveness for my father," she said. "I felt very guilty that I might have opened up a can of worms. I didn't want him to go to jail. I even thought about warning him to leave the country."

Instead, she obtained old newspaper articles about the murder, spoke to relatives about what they knew, met with detectives and eventually hired her own private investigator, who was allowed to review the police file.

Each new email attachment and brown manila envelope from California made her more convinced of her father's guilt, she said.

When she read how the killer had tied up the corpse with ropes, she shuddered. She said her father was clever with ropes and used them often, creating handholds for boxes and once devising a rope pulley to hang a picture high on the wall.

During a 2010 visit to Foster City, Alison sat in a small, windowless interview room with two detectives and telephoned her father. The detectives listened in and coached her, she said.

Patrick said he didn't kill her mother, but called her death the best thing that could have happened to Alison, she said. He said he would have killed her mother for Alison's sake but someone beat him to it, according to Alison. It was their last conversation.

Because the investigation remains open, Foster City police refused to discuss the case. Police also declined to give a copy of the recording to Alison's lawyer or to her private detective.

I didn't want him to go to jail. I even thought about warning him to leave the country."— Alison Galvani

In November 2010, her father sued her over property she had loaned him money to buy. He wanted to remove her as co-owner. Alison filed a wrongful death lawsuit against him the next month. She said her private investigator's report had ended her doubts and she wanted him held accountable.

Her father rehired Keker, the lawyer who had represented him decades earlier. Keker attributed Alison's lawsuit to "a sad family feud." He said she had discovered nothing to prove her father killed her mother.

Though the criminal case remains open, "we have exhausted every lead," said Foster City Police Captain Frank Derris, who met with Alison. "There is nothing to move on at this point."

A federal appeals court ruled in November that Alison had filed her wrongful death lawsuit too late. Under California law, she should have sued within two years of first becoming suspicious. The court decided the two-year statute of limitations began when she accused her father of murder in early 2008.

The court said the police file on her father, "which contained a factual basis for her claim," was made available to her private investigator in June 2009, within the two-year period when she could have sued. Alison had argued she did not have enough evidence to sue until she received her private investigator's report in 2010.

She said she hopes new information uncovered by the investigator will persuade San Francisco prosecutors to bring charges.

Though the lawsuit's dismissal was a setback, Alison said her search for evidence has been cathartic. She is writing a memoir. It begins with the picnic with her mother.

"My mother's vindication is that she has a daughter who loved her enough to try as hard as I did to get justice," Alison said. "My father lost that love, and that is his punishment."

Follow Maura Dolan (@mauradolan) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

A private club more about young blood than blue

You're seen much more as having value than being some young whippersnapper."

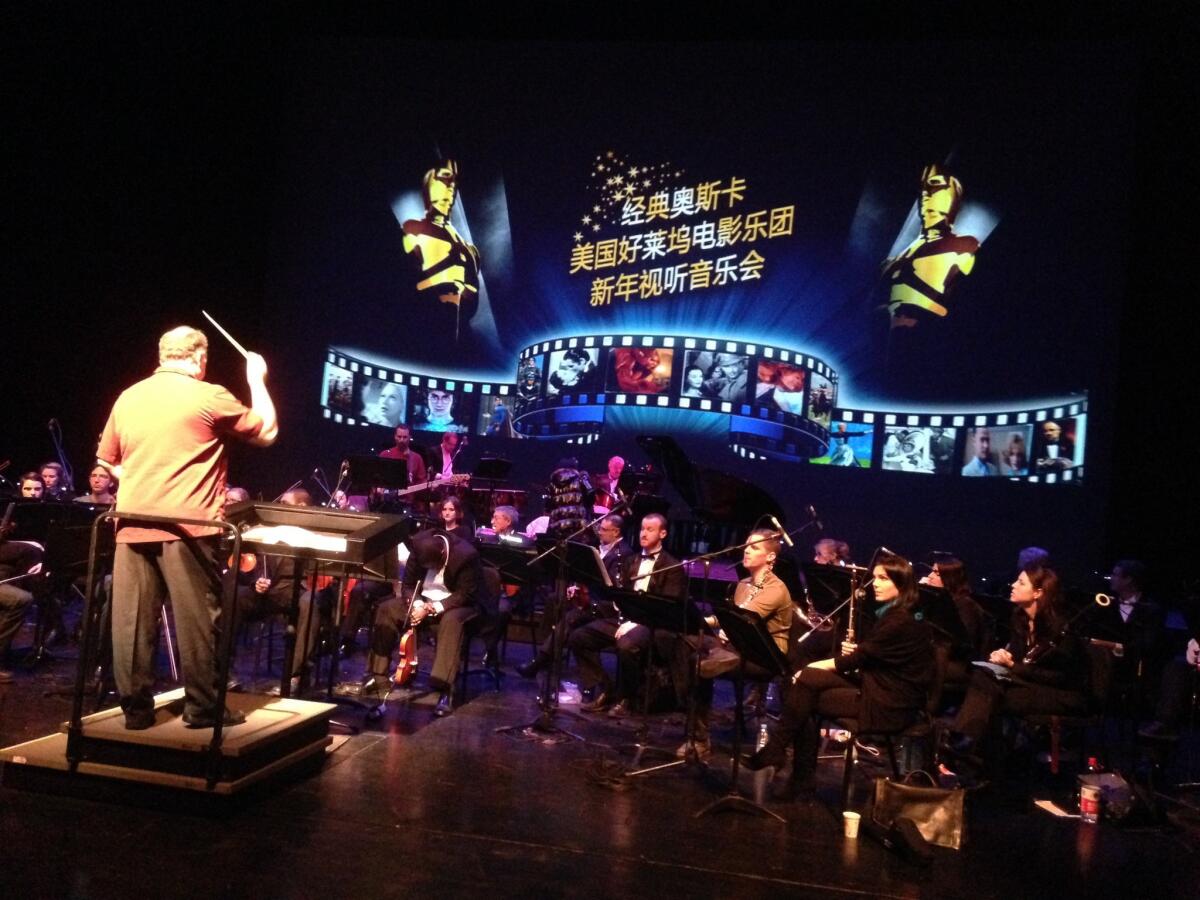

An atypical orchestra offers music for China's masses

When we got there to rehearse the day before, they were still building the bathrooms."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.