Defendants declared mentally incompetent face lengthy delays in jails

- Share via

In January 2014, Edward Lamont Mason allegedly attacked and injured a woman with a baseball bat.

He was arrested and has been in jail ever since, even though a judge ruled he was unfit to stand trial.

Mason, it turns out, is developmentally disabled. The victim of the alleged assault was his caretaker. And while the judge ordered him sent to Porterville Developmental Center — the only state hospital set up to house and treat developmentally disabled criminal defendants — there is no room.

So while the case against the Hayward, Calif., resident has been temporarily suspended, he remains an inmate in Alameda County’s Santa Rita jail, not receiving the treatment that would allow his case to move forward.

Mason’s lawyer, assistant public defender Brian Bloom, said if his 37-year-old client had been convicted and sentenced, he probably would have served less time than he has now spent waiting for a hospital bed.

“He’s confined in jail for no other reason than he’s developmentally disabled, which is really quite horrific when you think about it,” Bloom said.

State officials say there is nothing they can do about it. A backlog of mentally ill or developmentally disabled defendants who have been ruled incompetent to stand trial has become a persistent problem that judges, lawyers, doctors and jailers are scrambling to resolve.

There are about 50 inmates like Mason in jails around California, waiting for beds to open up at Porterville, which they rarely do. As of early March, Mason was number 13 on the list.

More than 300 other inmates with diagnoses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are also waiting for beds in the five other state hospitals that treat mentally ill defendants.

Officials and advocates across the board agree that the backlog is costing taxpayers money and delaying treatment for the accused as well as justice for them and their alleged victims.

In some counties, including Los Angeles, lockups are already under scrutiny over their treatment of mentally ill inmates. More state money could build and staff additional hospital beds, but some officials want to first see whether the problem will be eased by Proposition 47 — which has already reduced overcrowding in county jails by slashing penalties for many property and drug crimes.

State analysts also believe the Department of State Hospitals needs to better manage the resources it has now. In some cases, hospital beds remain empty despite the waiting list.

In the meantime, the state wants counties to treat more mentally incompetent inmates in the jails, a potentially cheaper solution that has won some support but also raised the hackles of defense attorneys and advocates who say jail is not the right setting for such patients.

Once a judge finds a felony defendant is incompetent to stand trial, the person is supposed to go to a state hospital for treatment and training until he or she is able to understand the criminal charges and help an attorney prepare a defense. In cases where the illness is too severe for a trial to go forward, a patient can remain hospitalized for as long as three years.

The number of mentally ill and developmentally disabled defendants awaiting transfer to state hospitals at any given time rose to 376 last year from a monthly average of 162 in 2012. State and county officials offer a variety of explanations, including cutbacks in county mental health services during the recession that may have led to more mentally ill people committing crimes, and difficulties attracting enough psychiatrists to work in the hospitals, which would enable them to take in more patients.

“It’s a huge problem, for a number of reasons,” said Judge James Bianco, who rules on cases in the mental health court in Los Angeles. Bianco keeps a running stack of cases in which defendants have been waiting more than a month for transfer to state hospitals, and he calls in state officials weekly to explain the delays. “These are people who are severely mentally ill, who need to be in treatment at a state hospital rather than in jail.”

In Los Angeles County, more than 100 yet-to-be-tried jail inmates are waiting for state hospital beds. On average, sheriff’s officials said, they wait in jail for 21/2 months after being declared incompetent before they are transferred to state hospitals.

The waits are often longer for developmentally disabled inmates.

Gary Donnell Williams, a developmentally disabled L.A. County jail inmate, waited for three years. During much of that time, state and county agencies were wrangling in court over who should be required to take him. Williams was accused of sexually assaulting a woman with Down syndrome who he had met on a bus. A judge found Williams incompetent and ordered him sent to Porterville, but the hospital refused to take Williams — who also had medical issues and was wheelchair bound, according to court documents — saying he would endanger other clients.

Finally, after an appeals court ruled that Williams was being illegally held, he was released to a South Los Angeles group home in October.

A recent report by the state legislative analyst’s office noted that Proposition 47 could reduce the demand for state hospital beds. A separate report by Los Angeles County said some 400 inmates in state hospitals who have been found incompetent to stand trial might be eligible for release if their crimes are reduced to misdemeanors. That has raised concerns among county mental health workers, who say an exodus of patients from state hospitals could strain local resources.

But as of February, the Department of State Hospitals had only been ordered to release 17 mentally ill people whose charges were reduced under Proposition 47, a spokesman said. Fourteen others were removed from the waiting list. No patients have been released from Porterville under the new law.

In the meantime, at the urging of the state, San Bernardino and Riverside counties have launched in-jail treatment programs for a small number of mentally ill felony defendants, although not those who are developmentally disabled. Los Angeles County is considering following suit.

The program would have some financial advantages, as the state would pay to house and treat the inmates in the county jail. Currently, the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department receives no reimbursement for housing inmates awaiting transfer to state hospitals.

Some advocates, attorneys and treatment providers are adamantly opposed to the proposal.

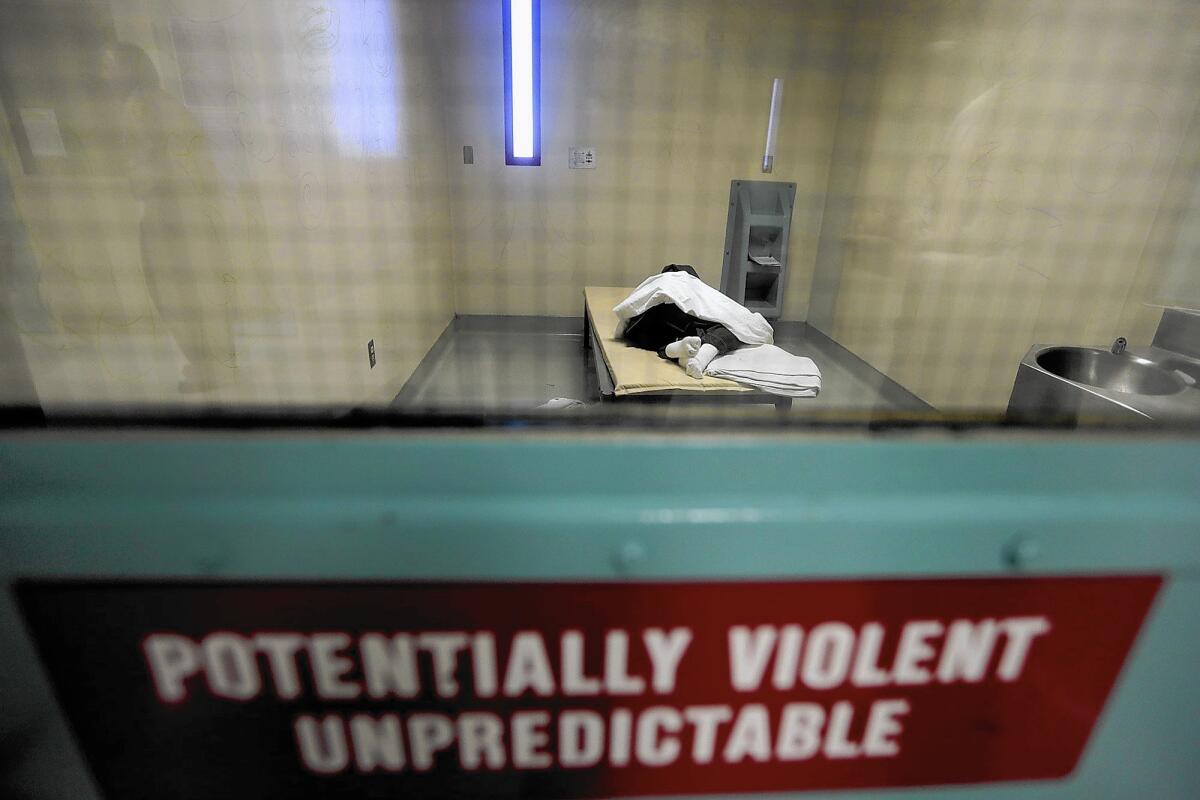

“I think it’s a foolhardy idea,” said Terry Kupers, a psychiatrist who specializes in jails. Mentally ill jail inmates spend most of their time in a cell and, in some cases, in isolation, which can exacerbate their symptoms, he said.

“Of course it’s possible to do quality treatment in the jails,” Kupers said. “I’ve just never seen it happen.”

Assistant Sheriff Terri McDonald, who oversees the jails, argued that the program could, in the short term, help the county, the state and the inmates.

“State hospital beds don’t get built overnight,” McDonald said. “I’m not convinced this is a long-term solution, but as a temporary solution our goal is to get these inmates the treatment they need and get them back into the criminal justice system.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.