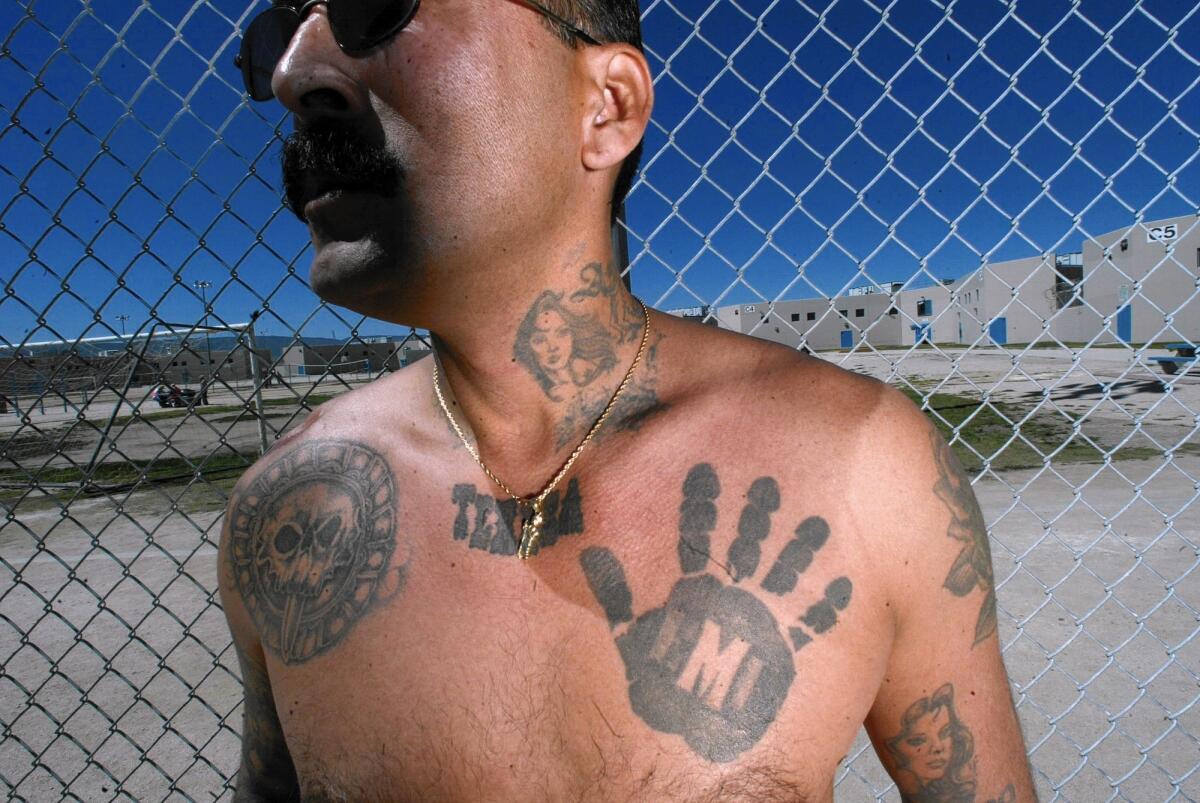

Children of victim upset that Mexican Mafia killer may be paroled

- Share via

The girl was 8 years old and her little brother 6 when their mother was fatally shot and left in a vacant lot. Although Cynthia Gavaldon’s body was identified on Christmas Eve, the children’s father waited until after the holiday to tell them their mother was in heaven.

For years, they had unanswered questions. It was only two decades later, when the daughter was reading a book about former Mexican Mafia shot-caller Rene “Boxer” Enriquez that she found out more: He had ordered her mother killed.

In an interview this week, Gavaldon’s now-adult children said they were horrified to learn that a state parole board had decided Enriquez should be released from prison. The siblings said they were upset that they were never informed that the prison system was reviewing whether to release Enriquez, who pleaded guilty to murdering Gavaldon and a man in 1989 and was sentenced to life in prison.

The pair, who asked that their names not be used because of fears for their safety, said they learned about Enriquez’s parole — and that Gov. Jerry Brown has until Feb. 22 to decide whether to block it — only when a Times reporter contacted them this week.

“He stole a piece of our lives from us,” Gavaldon’s daughter said of Enriquez. “And it’s not fair.”

A Los Angeles County district attorney’s spokeswoman said a prosecutor who attended Enriquez’s parole hearing had no contact information for the victims’ family.

A state prison spokeswoman said that under state law, victims’ relatives are sent notifications at least 90 days before a parole hearing — if they submit a request. The Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation received no such requests from Enriquez’s victims or their relatives, the spokeswoman said.

But several legal experts said that Gavaldon’s relatives should have been made aware of the parole hearing in September under California’s 2008 victims’ bill of rights, Marsy’s Law, whether or not a request was made. Some noted that the law does not explicitly say which agency is responsible for giving the notification but agreed that the children should have been told.

“Should they have been informed? Absolutely,” said Mike Fell, a former Orange County prosecutor who handles victims’ rights cases as a private attorney.

Gavaldon’s son said he was angry that he never had the chance to address the parole board. Had he known about the hearing, he said, he would have submitted a letter objecting to Enriquez’s release and would have encouraged his relatives to do the same. He said he might have reached out to the family of the other person Enriquez was convicted of killing to see if they would help.

During his parole hearing, Enriquez explained that he had dropped out of the Mexican Mafia prison gang in 2002 and started working with authorities, providing expert testimony and other assistance in scores of cases. He presented letters from officials at 11 law enforcement agencies praising his work.

He expressed remorse for his crimes.

In 1989, while on parole, Enriquez came to suspect that Gavaldon, 28, was stealing drugs from him that she was supposed to sell, according to court records. Enriquez “wanted to set an example” and ordered her execution, according to a probation report in the case. She was shot once in the head and once in the upper body.

About a week later, Enriquez targeted a member of the Mexican Mafia who had fallen out of favor with the gang for running away from a fight, according to parole records. Enriquez said he gave the victim an overdose of heroin and then shot him five times in the head, leaving him in an alley.

While awaiting trial, Enriquez and another inmate jumped a man in a jailhouse waiting room, stabbing him 26 times with metal shanks. In another incident, Enriquez stabbed a second man while in custody. Both men survived the attacks.

He pleaded guilty to two counts of second-degree murder and was sentenced to life in prison.

During his parole hearing, Enriquez described Gavaldon’s death as “one of those things that I wish I could take back.” His lawyer advised him to invoke his 5th Amendment right against self-incrimination when he was asked if he was involved in any other killings.

Gavaldon’s children said they were devastated by their mother’s death. Her son remembers sitting in a second-grade classroom surrounded by other children, wondering why it was his mother and not someone else’s who was killed.

His sister still prays for their mother. They grapple with what to tell their own children about the grandmother they will never know.

Gavaldon’s children recalled their mother as a woman who adored them, kept a clean house and made homemade tortillas when her father-in-law came to visit. She taught her son and daughter the alphabet and numbers at a young age. In a photo Gavaldon’s son keeps on his iPhone, the redheaded woman cradles her baby son in her lap with her daughter at her side. The young mother is beaming.

“Everybody noticed her smile,” Gavaldon’s daughter said. “She could basically walk into a room and take it over.”

But in the last year or so of Gavaldon’s life, her children said, she hit a rough patch. They went to live with their father — their parents had divorced years earlier — and although their mother still showed her love for them, they noticed something different. There were always a lot of people at her house. She got involved in drugs. Her daughter began to pray every night: “Please, don’t let anything bad happen to my mom.”

Growing up, Gavaldon’s children said, they heard rumors about their mother’s death but never knew exactly what happened. Her daughter learned from relatives that their mother was murdered “execution-style.”

In 2008, Gavaldon’s daughter was shopping at Barnes & Noble with her husband. She saw a recently published book about a man who spent decades with the Mexican Mafia. She thought it looked interesting and bought the book.

She was reading Chapter 14 — she still remembers — when she saw her mother’s name. The book, “The Black Hand: The Story of Rene “Boxer” Enriquez and His Life in the Mexican Mafia,” described Gavaldon as a party girl. It detailed the conversation in which Enriquez ordered her death, with the former gangster calling the hit “a ride to hell.”

Her daughter called her husband sobbing.

“I couldn’t breathe,” she recalled, breaking down in tears. “Oh my God. I just, I couldn’t.”

The siblings said their great-grandmother — who helped raise their mother — became afraid after the book was published that the gang would find their family. Gavaldon’s children said the same thought has crossed their minds, especially now that they have their own families to consider. Those same concerns surfaced, her son said, now that he knows Enriquez could be paroled.

“I would do whatever I could do to stop it,” Gavaldon’s son said. “Because it’s not right. Something has to be done.”

Twitter: @katemather

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.