Homicide rates drop as Richmond chief builds bond with community

- Share via

Reporting from RICHMOND, Calif. — Residents packed the City Council chambers here in 2005, hoisting signs emblazoned with photos of slain loved ones. Eight men had been shot dead in gang-related violence in a two-week span.

Many residents had long had contempt for the Richmond Police Department, with its decades-old reputation of racism and ruthlessness. The community rarely cooperated with officers, making even minor crimes hard to solve.

New to town, City Manager Bill Lindsay believed that change would come only with an overhaul of police practices. He turned to an unlikely reformer: Chris Magnus, the white, gay police chief of Fargo, N.D.

A decade later, this minority-majority city has recorded its lowest homicide rate in 33 years. Officer-involved shootings are now rare: There have been two since Magnus came on board, whereas outside police agencies killed five men inside city limits during the same period.

Community mistrust has gradually given way to collaboration, thanks to deepening bonds between officers and the neighborhoods they serve.

Now, as angry residents riot over use of force in Baltimore — and Ferguson, Mo., before that — state and federal leaders are tapping Magnus, 54, to share his approach.

Magnus acknowledges that the gains have involved some luck. But he and outside experts attribute them largely to a hard-won culture change.

Residents have also stepped up.

“We changed some of the ideas the police had about us, and we changed some of the ideas we had about them,” said Bennie Lois-Clark Singleton, 80, who participates in weekly street walks to coax at-risk youths to reject violence.

::

The video went viral. Two officers working the annual Juneteenth festival were showing off their moves to the line-dance hit “the Wobble.” Onlookers hooted encouragement.

The resident who captured the scene at the celebration of African American history later called it “awesome” to see how the officers “were interacting with the community.” But it wasn’t always so.

A shipbuilding hub during World War II, Richmond struggled when jobs vanished. The urban core is still depressed in this city of 107,500 — more than 80% of whom are nonwhite — and a dozen gangs remain active.

In 1982, minorities’ relations with police boiled over when tactics of officers known as “the Cowboys” came into wider light. Separate fatal police shootings of two black men in their beds led to a $3-million judgment, then the largest civil penalty in the country for police abuse.

A judge noted “significant” evidence of an informal policy that “encouraged and authorized violence and brutality by Richmond police officers against black residents.”

As demographics shifted, problems persisted. In 2002, officers clearing a street on Cinco de Mayo roughed up and pepper-sprayed Andres Soto and his sons. In a holding cell, Soto found more than a dozen other Latino men swept up by police. The community protested. The group won a settlement.

“That was the crack in the mirror,” said Soto, 59, an environmental activist.

Two interim chiefs followed. Then, in December 2005, Lindsay hired Magnus, who had climbed the ranks in Lansing, Mich., before heading the force in Fargo.

“He just completely opened up the department,” Soto said.

::

When Magnus arrived, he quickly realized he had to craft a command team committed to the vision of “more human relationships,” he said.

There were challenges. Soon after he took the post, seven high-ranking African American officers sued, accusing Magnus of making racist comments and bypassing them for promotion. The case dragged on for years. After a three-month civil trial in 2012, the officers lost on all 72 counts.

All the while, the chief was pressing reforms.

He disbanded roving street teams that had focused on arrests, replacing them with neighborhood-based policing. Officers attend neighborhood meetings and give out their cellphone numbers. The department installed monitored street cameras and a gunfire detection system and employed sophisticated software to better predict and prevent crime.

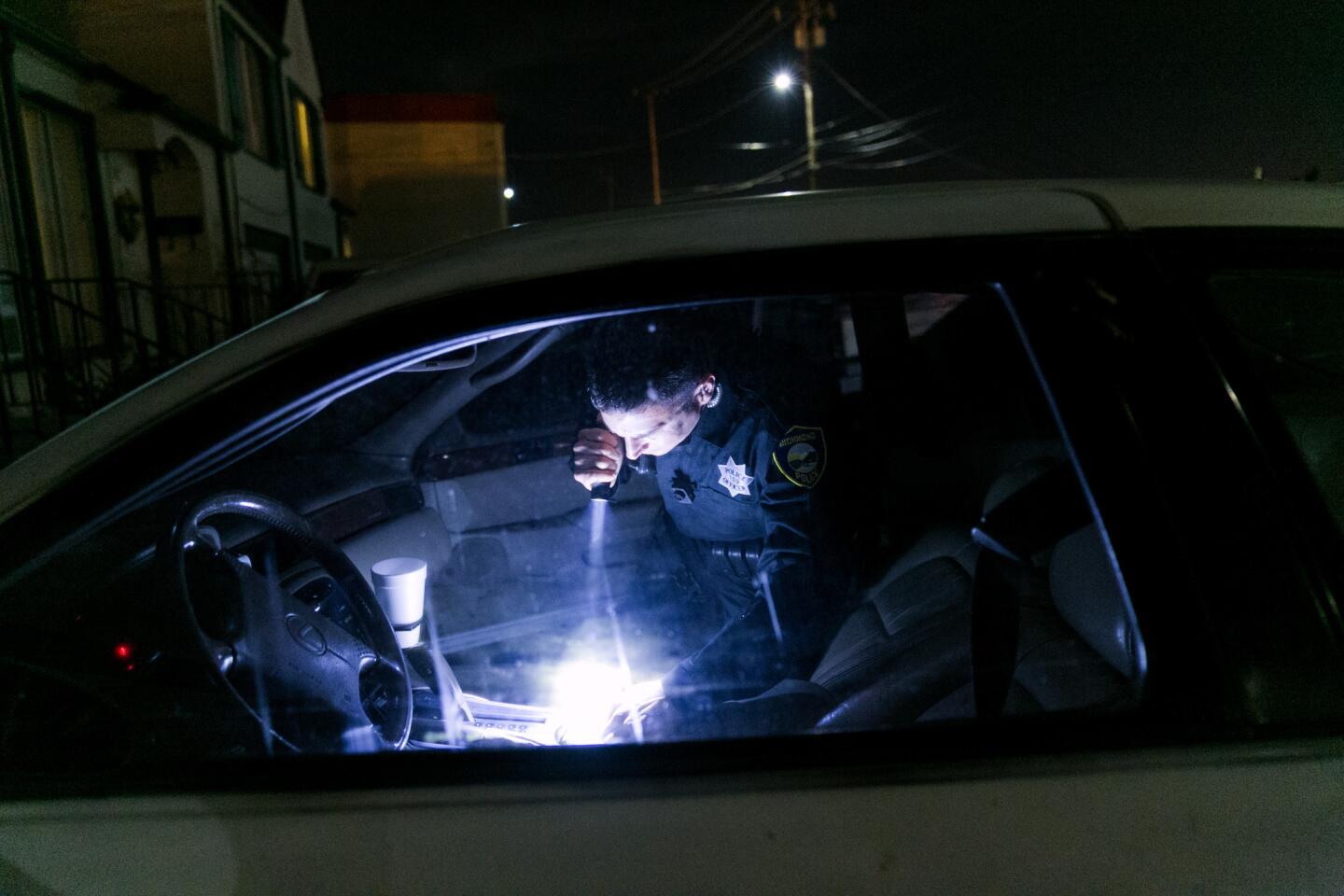

On a recent shift, Officer Chris Llamas edged his patrol car over the railroad tracks. Members of a Norteño gang had entered Sureño territory to leave their tag, which Sureños had crossed out and replaced with their own. It could easily escalate into shooting, the 13-year veteran concluded.

Code enforcement workers now fall under Magnus’ command, leading to quicker action on graffiti, drug houses and other blight. The tags would “be gone by tomorrow,” Llamas said after making a call. Soon, he and his partner were rousting public drinkers in a parking lot. A new merchants association had asked for help with the loitering, and received it.

Enlisting community members as partners has also yielded benefits.

Richard Boyd, an organizer with Contra Costa Interfaith Supporting Community Organization, recalled that when he moved to Richmond, shortly before Magnus did, young men loitered in his neighborhood, flashing guns and shooting dice.

“There was no genuine policing, there was no genuine street cleaning, road repair services,” Boyd recalled. “They wouldn’t respond to any quality-of-life issues.”

That soon changed. Though still troubled by violence, the Iron Triangle neighborhood has calmed noticeably, and families with children play in a radically revamped Nevin Park.

“We were able … to call [the beat officers] directly and say, ‘There are eight guys out front gambling,’” Boyd recalled. “And those officers would respond because they could feel our pain.”

Through Boyd’s interfaith group, clergy lead the weekly street walks and participate in an anti-violence program known as Ceasefire, attending “call-ins” where police are also present to persuade active members to give up gang life.

“I wouldn’t call it trust, but they just know each other,” said Tamisha Walker, 32, a one-time offender who runs a reentry program for former inmates. “The officers know the guys on the street, they know their families, they know that they have kids, if they’ve been to school.”

But work remains. “It is individual officers and not the department as a whole that is respected,” said Walker, who encourages offenders through Ceasefire to give up violence. “We still have officers who we need to be careful about.”

Toody Maher concurs. In collaboration with police, her Pogo Park nonprofit transformed a blighted lot into a vibrant park that employs residents as monitors and won a national award.

“Sometimes the events on the ground don’t correspond with the vision,” she said, “but thank God we have the vision.”

::

The police supervisors gathered for a routine meeting — to pick apart every incident of force over a two-month period. Each tackle of a fleeing suspect, arm-twist and kick was up for scrutiny, though none had prompted complaints.

A woman outside an apartment where a kidnapping involving a gun was unfolding had refused three orders to move. When an officer sought to arrest her, a physical struggle ensued. The incident, the group concurred, had stoked emotions and proved a poor use of resources.

“It’s a good big-picture training point,” offered Officer Steve Andretich, the use-of-force trainer. “Maybe [the officer] could have said to the other witness, ‘Hey, this is why we want you to move. Can you ask her?’”

Weapons training has also expanded. Shooting-range sessions are held monthly to enhance precision. Quarterly, officers run through role-playing scenarios to help with split-second decisions on when to shoot and when to instead use Tasers, pepper spray or verbal persuasion, said Lt. Louie Tirona, the firearms instructor.

They are also taught to stop when a suspect complies, and Tirona said he has found that rounds fired have “decreased noticeably,” contributing to a higher survival rate of suspects. In four of the seven nonfatal police shootings under Magnus’ watch, officers fired only one round.

Laurie Robinson, a professor of criminology at George Mason University who co-chaired the Presidential Task Force on 21st Century Policing — convened in the wake of the Ferguson unrest — called Richmond’s monthly use-of-force reviews “highly unusual.” She said role-playing training, although more common in larger departments, puts Richmond on the “leading edge of good practice.”

Magnus was one of “the most impressive” of the more than 120 people invited to testify before the task force, Robinson said, because he has forged collaborations with “not just the residents but churches and schools and social services and businesses.”

But, she said, it is the combination of reforms — better training, community policing and new technologies — that truly set Richmond apart and could prove a model for other departments large and small.

A national expert on recognizing implicit racial and gender bias conducted department-wide training in February. Weeks earlier, officers filled a conference room for a meditation training geared to help them remain relaxed, alert and focused.

Sgt. Robert Gray, a 25-year veteran who proposed the training, said it would have been laughed at a decade ago.

The idea of old-school cops, he said, “was to get the bad guys, get them to comply, and if that takes physical coercion, so be it. That’s not the way to be, especially when you serve the community. And that’s what we are — servants.”

Last September, after the city had gone seven years without a fatality, a Richmond officer shot and killed Pedie Perez, 24, contending that Perez grabbed for his gun. Perez’s family disputes that version and has sued. An investigation is ongoing. Body cameras have since arrived.

Magnus knew community relations were at risk. He informed the public that it could attend the coroner’s inquest; posted updates on social media; and was present at Perez’s funeral at the family’s invitation.

Last winter, the chief joined community members demonstrating in the wake of the Ferguson unrest and held a “Black Lives Matter” sign.

The Richmond Police Officers Assn. bristled, accusing him of illegally participating in political activities while in uniform. Magnus countered that he was merely acknowledging that “all lives matter” and showing respect “for the very real concerns of our minority communities.”

Boyd did a double-take when Magnus reached for the sign but said he was not surprised. He had first met Magnus at a march to the scene of a slaying that, it turned out, had occurred in Magnus’ neighborhood.

There was this “blond-haired white guy going on about how he had heard the shots from his house,” Boyd said. “Sometimes I think he doesn’t know he’s the chief. He thinks he’s one of us.”

Twitter: @leeromney

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.