The San Quentin Six: How a wig and a handgun sent a prison into chaos 44 years ago

The San Quentin State Prison, which houses the 729 men on California death row. There are 21 women on death row at the Central California Women’s Facility near Chowchilla.

- Share via

Forty-four years ago, a seemingly innocuous jailhouse rendezvous between a California inmate and his lawyer turned one of the nation's most storied prisons into a killing field.

George Jackson, the founder of the Black Guerilla Family prison gang who was awaiting trial for the murder of a guard at Soledad State Prison, sat across a table from his attorney, Stephen Bingham, inside San Quentin State Prison on Aug. 21, 1971.

At some point during the conversation, Bingham allegedly passed a handgun and several clips of ammunition to Jackson, who slipped the weapon under a wig. When the visit was over, Jackson used the gun to take a guard prisoner, and forced him to unlock the cells of more than two dozen prisoners.

The riot that followed would last just 33 minutes. But it left six people dead, including Jackson, and plunged California prosecutors into a years-long criminal trial, one dogged by allegations of racism and rampant conspiracy theories that the government planned Jackson's escape so they could assassinate him.

Hugo Pinell, one of the six inmates charged in the bloody escape attempt, was killed Wednesday night at a maximum-security facility outside Folsom. In a bizarre twist, he was stabbed to death, which triggered a riot. Nearly four decades earlier, he was charged with slashing a corrections officer's throat during the San Quentin riot he allegedly helped start.

Pinell was the last of the six to be imprisoned after alleged involvement in what many consider to be one of the bloodiest prison riots in U.S. history.

------------

FOR THE RECORD, Aug. 14:

In an earlier version of this story, Willie Tate was identified as the final member of the "San Quentin Six" who remained in the California Prison System. A corrections department spokesman said Friday that the Willie Tate who is incarcerated in a prison in Soledad is not the same person who was acquitted in the 1971 riot at San Quentin. That man was released from prison in 1976.

------------

The escape attempt

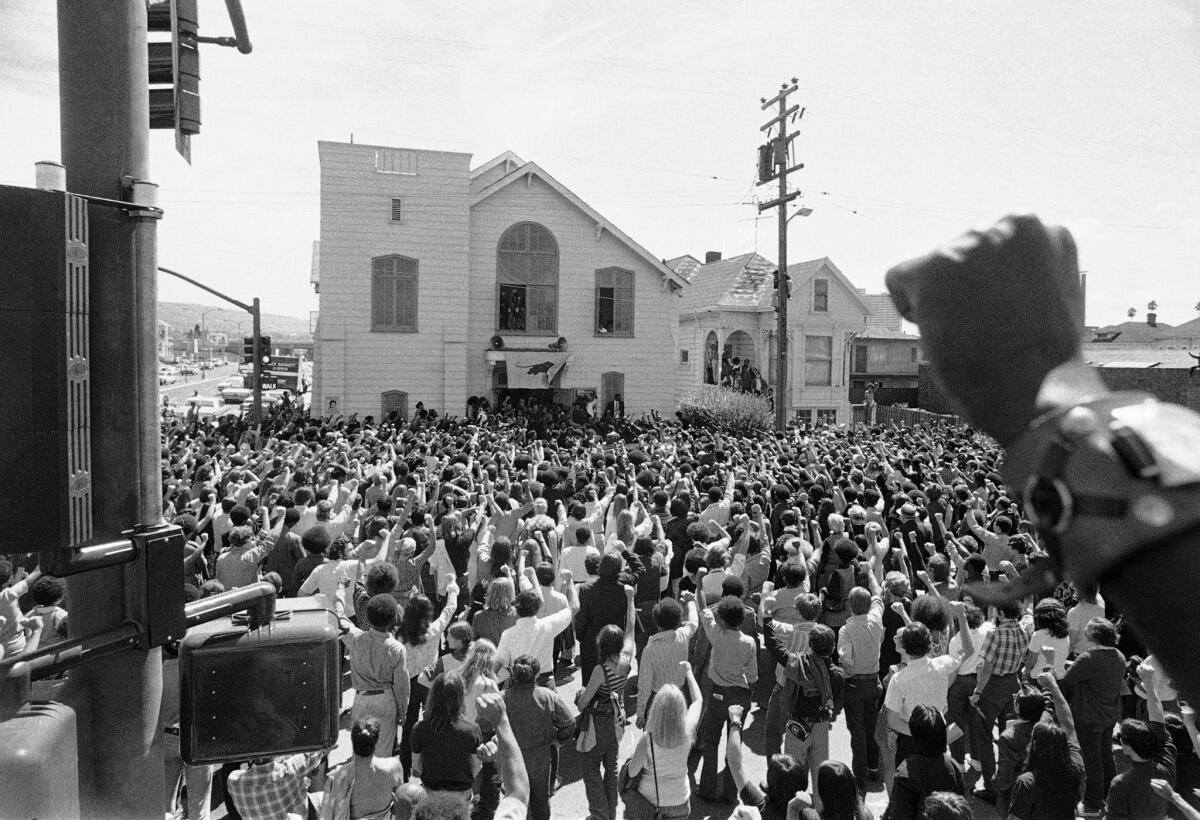

About 1,500 mourners give the Black Panther salute as the body of slain Soledad Brother George Jackson was carried from St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church in Oakland, Calif. on Saturday, Aug. 28, 1971. They shouted “Power to the people!” Jackson was shot to death by guards last Saturday apparently when he attempted to escape from San Quentin Prison.

About 1,500 mourners give the Black Panther salute as the body of slain Soledad Brother George Jackson was carried from St. Augustine's Episcopal Church in Oakland, Calif. Jackson's funeral was held a week after he was killed during the escape attempt. (Associated Press)

After finishing his meeting with Bingham, Jackson used a 9-millimeter handgun to take corrections officer Urbano Rubiaco hostage. He forced the guard to open several prison cells, and the prison quickly erupted into chaos.

Jackson was soon joined by a group of inmates who would become known as the "San Quentin Six:" Pinell, John Larry Spain, Luis Talamantez, Willie Tate, David Johnson and Fleeta Drumgo. Drumgo had been charged alongside Jackson in the murder of the corrections officer at Soledad. All six were later charged with murder and conspiracy in connection with the escape attempt.

Once the cells were opened, the inmates tied up Officers Frank DeLeon, Paul Krasenes and Kenneth McCray. Officer Charles Breckenridge was then taken prisoner at gunpoint and put in a cell with Rubiaco.

The first guard would be killed a short time later, when Jackson took Officer Jere Graham hostage and shot him to death. Pinell then stabbed Breckenridge in the neck, according to an indictment handed down in Marin County.

DeLeon, Krasenes and two white inmates, John Lynn and Ronald Kane, were all shot and stabbed to death. Their bodies were piled up in a single cell, and formed a pool of blood that one prison official later described as "literally one inch thick."

As police from surrounding cities were scrambling to get to the prison, Jackson was shot to death while he tried to flee the prison. He was the final man killed during the riot that was supposed to mask his escape.

The wild scene at San Quentin that day was actually the second time Jackson's imprisonment had inspired bloodshed. His younger brother, Jonathan, was one of four people killed during a shootout with police outside the Marin County Courthouse in 1970. Jonathan Jackson had taken a Superior Court judge hostage in an attempt to win his older brother's freedom.

A years-long trial provided few answers

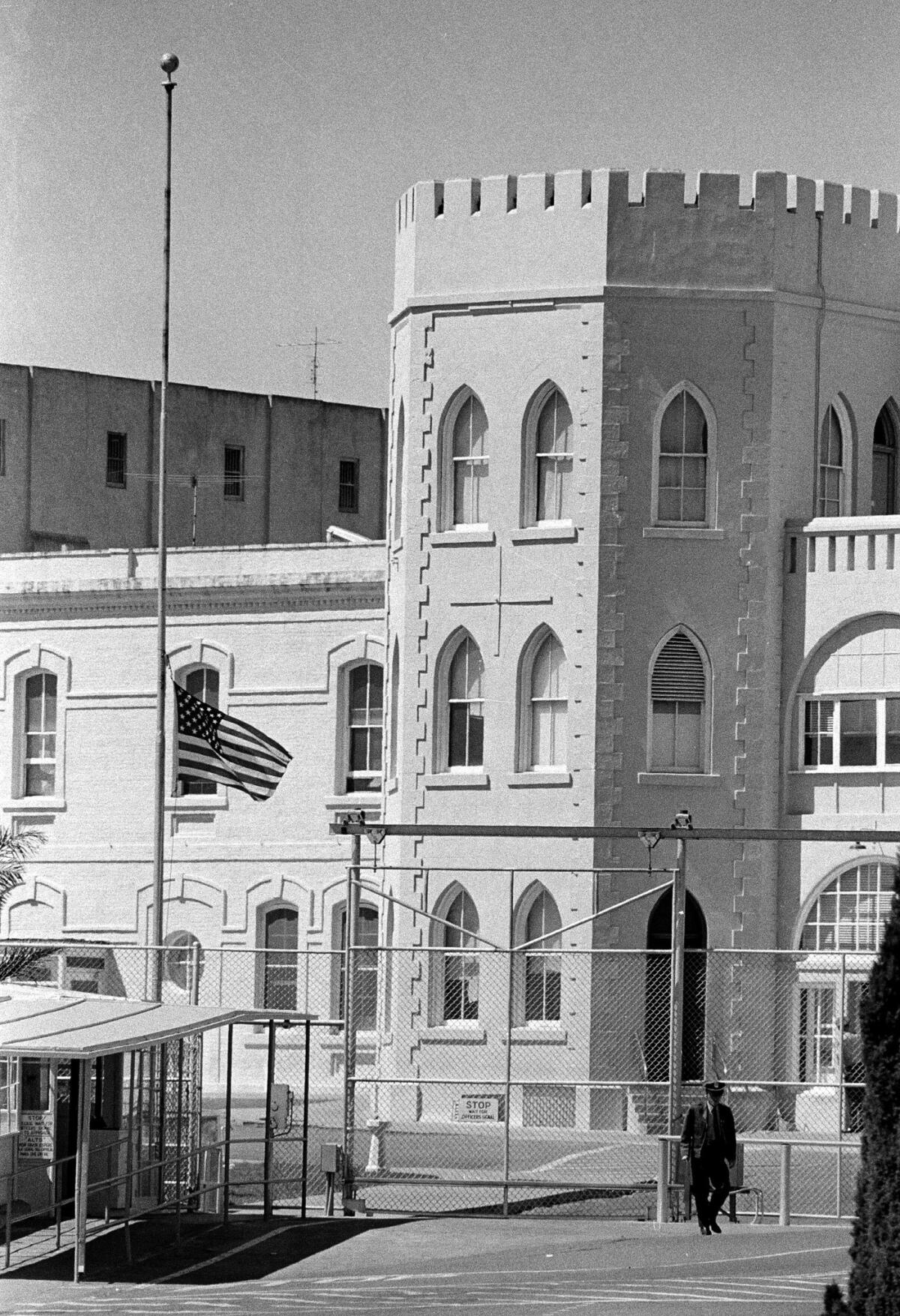

The flag outside the prison walls at San Quentin flies at half mast, Aug. 22, 1971, in honor of three slain guards killed as violence broke out Saturday afternoon. Three guards and three inmates were slain.

The flag outside the prison walls at San Quentin flies at half-staff on Aug. 22, 1971, in honor of the three slain corrections officers. (Associated Press)

All six inmates, and Bingham, were indicted on murder and assault charges two months after the riots. But their trial wasn't over until 1976. Bingham fled the country, and did not stand trial until 1986.

Controversy began swirling around the case immediately after the indictment was handed down, when several grand jurors walked out of the courthouse and claimed the proceedings had been manipulated to discriminate against non-whites. Five of the six defendants were black, and Pinell was Nicaraguan.

An appeals court overturned the indictment, agreeing with claims that the Marin County grand jury proceedings had discriminated against the minority defendants. But the state court of appeals reversed that decision in 1974, finally setting the stage for a trial.

At the trial, the defense repeatedly argued that Jackson's escape was actually orchestrated by law enforcement figures who wanted to use the melee as an opportunity to kill him. The Black Panther Party actually paid attorney's fees for five of the six defendants, though Pinell chose to represent himself.

Pinell testified that prison guards arranged for the escape to happen, and that the riot actually began when a guard pointed a gun at Jackson, not the other way around. In one tense moment at trial, while Officer Rubiaco was on the stand, Pinell asked "who cut your throat?"

"You did," Rubiaco replied.

Despite the torrent of blood inside San Quentin that day, only Spain was convicted of murder after a 16-month trial. Although Spain did not shoot or stab any of the guards, he was convicted of conspiring with Jackson in the escape that caused the guard's deaths.

Pinell and Johnson were convicted for assaulting correctional officers. Drumgo, Talamantez and Tate were all acquitted and released on parole for their prior crimes.

Bingham, the attorney, fled the country and did not return to the U.S. to face trial in 1986. He was eventually acquitted of all charges.

What happened to the San Quentin Six?

Pinell, 71, died Wednesday after he was stabbed by at least two inmates at California State-Prison in Sacramento, triggering a prison yard riot that involved roughly 70 inmates, corrections officials said. No officers were injured, but 11 prisoners were treated for stab wounds, broken bones and head trauma at area hospitals.

He had been serving six life sentences for a slew of convictions, including two connected to his attacks on Breckenridge and Rubiaco during the riots. Pinell was also convicted of rape in San Francisco in 1965 and in the killing of a guard at a prison in Soledad in 1971.

Pinell spent nearly all of his sentence in solitary confinement. The 43 years he spent in isolation were the most in state history, according to corrections officials. He was returned to the general population early last year as part of a response to a statewide hunger strike by inmates protesting the solitary confinement of inmates associated with prison gangs.

Drumgo was paroled shortly after his acquittal in 1976, but he was shot and killed three years later in Oakland. Talamantez was paroled on a prior robbery conviction less than two months after he was acquitted at trial.

Spain, who was the only member of the six convicted of murder at trial, was freed on parole in 1991. He later had his conviction overturned on the grounds that he was forced to wear shackles at trial in 1976, which could have prejudiced the jury. After he was released, Spain began lecturing troubled youths in the Bay Area.

Johnson, who was convicted of assault at trial, was released from prison in 1993.

Follow @JamesQueallyLAT for breaking newsUPDATES:

4:30 p.m.: This article was updated with additional information about Pinell's death.

This article first published at 2:53 p.m.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.