These 2 teens with similar backgrounds took very different paths to college

Guadalupe Acevedo, a senior at Theodore Roosevelt Senior High School in Boyle Heights, was surprised to learn that her grades and credits qualified her only for community college. “I was so lost. I didn’t know how college worked.”

- Share via

Guadalupe Acevedo is about to graduate from Theodore Roosevelt Senior High School, where most of the students come from low-income homes and the idea of applying for college blindsides many of the 368 or so seniors.

Lizbeth Ledesma is wrapping up her high school education at Chadwick School, where the only question for many of the 86 seniors is whether to go to an Ivy League, UC or prestigious liberal arts school.

Guadalupe and Lizbeth come from similar backgrounds.

Roosevelt and Chadwick, just 30 miles apart, are different worlds.

At Roosevelt, a Los Angeles Unified School District campus in Boyle Heights that’s surrounded by beauty shops, discount stores and a 400-foot-long mural depicting a fiercely anti-colonial history of the Americas, one counselor, his assistant and a counselor on loan from an outside group strive to help students find their way to higher education, often by way of community college.

At Chadwick, a private 45-acre hilltop retreat with an amphitheater that looks from Palos Verdes over much of Los Angeles, a team of four counselors preps members of the largely wealthy student body, beginning in ninth grade, in every nuance of how to win acceptance to the college of their choice.

The well-documented “achievement gap” in grades and graduation rates that separates rich and poor students at once affects and is affected by who gets into college. And by and large, those on one side of the gap get richer and those on the other get poorer, because people with college degrees make an average of 1.67 times as much money each week as those who don’t, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In the U.S., about 49% of high school graduates from low-income families enroll in college soon after receiving a diploma, compared with 80% of students from high-income families.

Recognizing the implications of that cycle for individuals and society, President Obama has set a goal for leading the world in college completion by 2020.

Meanwhile, with four years to go on that timeline, students nationwide — including Guadalupe and Lizbeth — still receive hugely disparate levels of support and coaching as they sprint or stumble across an uneven playing field toward their own college goals.

::

Guadalupe, a self-described “wild thinker,” entered high school wanting to be “a dancer, the next Selena, the next Beyonce.”

She lives in a house in City Terrace with her mother, who was raised in Mexico and works as a caregiver for people with disabilities.

Her mother, Guadalupe says, wanted to go to college but ultimately did not. Still, her mother motivated her with constant reminders about the importance of staying in school. Her father is out of the picture.

It wasn’t until earlier this year, when a teacher explained how hard it is to make a living in 21st century America with only a high school diploma, that Guadalupe snapped into reality, the 18-year-old says.

“I was so lost. I didn’t know how college worked.”

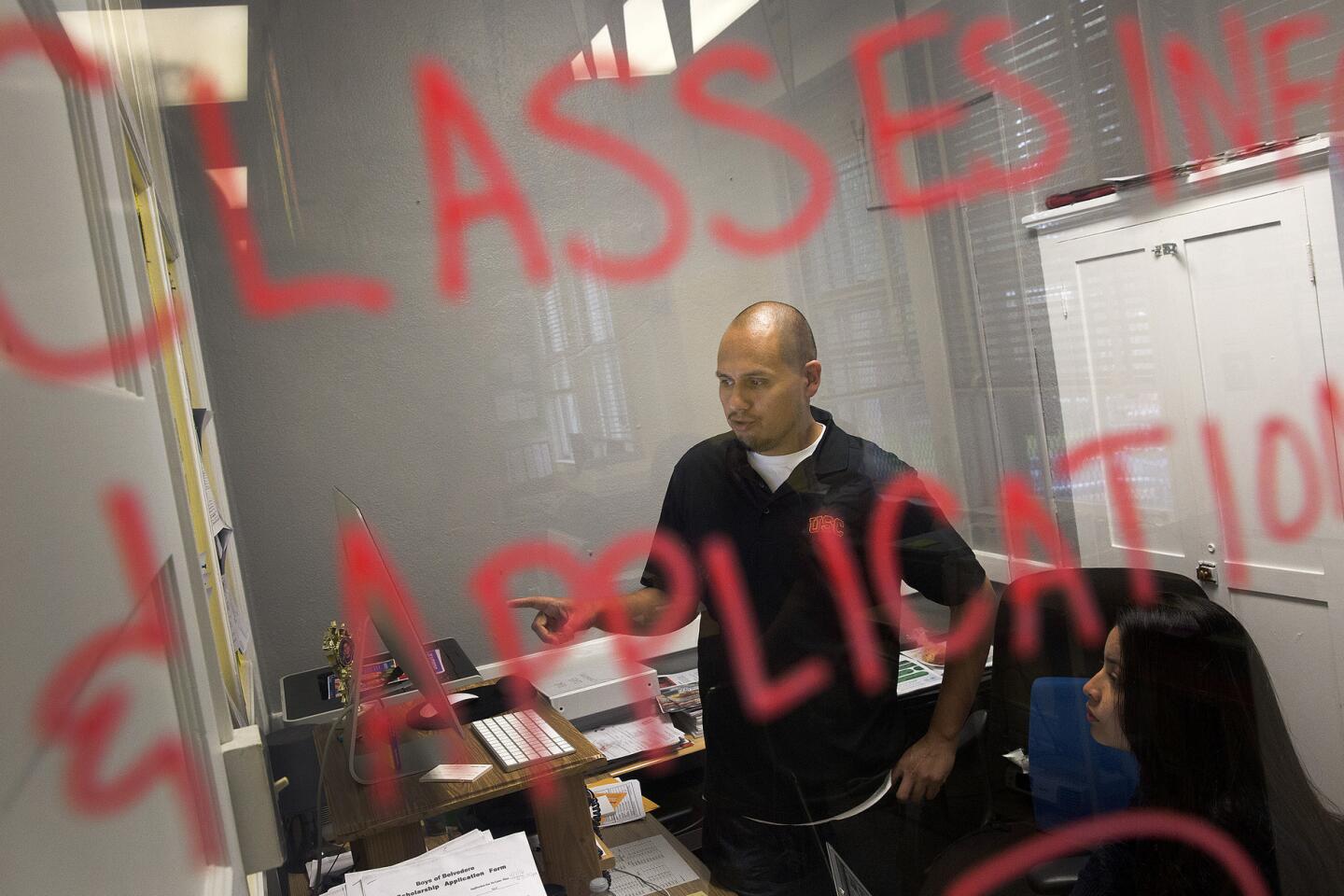

Raul Mata, the only full-time college counselor employed by Roosevelt, knows that “lost” story well.

Mata grew up in Huntington Park. There were plenty of students who didn’t accept the importance of college at Huntington Park High School, he says, but for some reason he wound up befriending the studious kids. His acceptance at USC — a school he chose for its football team — made him the first person in his family to go to college.

Today, too, he says, most students at Roosevelt grow up around adults who may not have finished high school, let alone attended college.

Last year, Mata started a program that tries to edge students who have decent but not stellar grades toward college. He has trained students to be peer counselors. And the next step, he says, will be targeting juniors to make sure they’re already aware of the college application process.

On a recent morning the 38-year-old stood in his small office, nudging a group of seniors to complete at least five scholarship applications.

It can be disheartening, he says. Many of his students are poor and come from homes so crowded or chaotic that studying is tough. Many simply don’t go to school.

“Some students are just resistant to the idea of college,” he says. “It’s hard to get ahold of them. But we try not to wash our hands of it.”

Then there are the school’s Guadalupes, who are ambitious but bewildered, and have the thinly stretched staff to turn to for help.

It does help, says Guadalupe as she stands outside the counselor’s office.

“Mata,” she says. “He has all the answers.”

::

Like Guadalupe, Lizbeth Ledesma, 17, is the daughter of parents who have little formal education.

She lives in an apartment in Inglewood with her five siblings. Because her parents aren’t fluent in English, they weren’t able to help much with homework, she says.

Still, she got straight A’s from kindergarten through eighth grade in the public schools she attended in the largely poor and Latino Lennox area. Grades alone do not ensure that a student is college-bound, but Lizbeth got an early break when, in sixth grade, she was selected for Young Eisner Scholars, a program that helps promising students get into private schools.

Lizbeth started at Chadwick in ninth grade — and struggled.

Almost all of the other students were wealthy, and expectations were high, she recalls. Teachers assumed she would know how to format a lab report — but at her old school there were no science labs, let alone reports.

By the time she hit 10th grade, Lizbeth became more comfortable, settling into a pattern of A’s and Bs. That’s also when she and her family first met with Alicia Valencia Akers, one of four college counselors at Chadwick — about one counselor for every 20 seniors.

Akers’ office opens into a room with two plush leather sofas and a fireplace mantle bedecked with college signs.

Akers’ curriculum vitae, like those of the other counselors at Chadwick, reflects high-level positions in the admissions offices of respected colleges — in her case USC’s Marshall School and Scripps College in Claremont.

Having seen the mercilessly competitive process from the other side of the application, Akers and her fellow counselors make sure freshmen know about the counseling office and start meeting with families by sophomore year.

Those meetings ramp up in junior and senior year, when students and their parents gather to parse the esoterica of admissions criteria and discuss schools that are good fits. They host essay-writing courses during the summers and after-school wine and cheese nights to help parents cope with letting their kids go.

The Chadwick counselors advise students not to apply to more than 10 colleges. But many do. And at least some of the stress during applications and admissions season, Akers says, stems from families flying around the country visiting campuses and having to make the tough decision about which of many college choices to accept.

::

Those who study society’s gaps — in academic achievement, college attendance and eventual income — say that one important factor is strong guidance in high school, if not sooner. Until public schools find a way to institutionalize solid college admissions support systems, students will continue to be lost and the nation’s college enrollment gap will remain a chasm that traps too many students from low-income homes, says UCLA education professor Tyrone Howard.

Not long after she realized that attending college was in her best interests, Guadalupe — with the help of a friend — began exploring her grades and credits. She was surprised to learn that she qualified only for community college.

At first, this caused her shame, she says. Then she realized that if she does well she can eventually transfer to a four-year college. She plans to start at East Los Angeles College in the fall, and hopes to transfer to USC, where she wants to take dance and Chicano studies and be a cheerleader.

Standing in the college center with the buzz of acceptance season swirling around her, she says the importance of the choices she made in recent months is only now sinking in.

Other students trooping through Mata’s office have been accepted at UC Irvine, UC Riverside, UCLA, Berkeley, Cal State L.A., Boston College, USC, Berkeley, UCLA, Georgetown and Cornell.

But that’s not the norm. Fewer than half of Roosevelt’s students were eligible to attend a Cal State or UC college this year.

If dramatically improving acceptance rates sometimes seems like an insurmountable challenge, Mata takes solace in knowing that his prodding can nudge generational change.

“It’s important to get these kids taking a step,” he says.

And he takes that lesson home, making sure his young son not only understands the importance of college but gets the message: “You must go.”

Lizbeth, who will graduate from Chadwick this spring, has a similar message for her sisters.

The 5-year-old, she says confidently, “will come to Chadwick — I’m really hoping she starts earlier than me.”

And she is determined to give the 12-year-old as much of a head start as possible. “The one thing I know for sure is I’m going to help her,” she says.

As for Lizbeth’s own plans, she, like most of her classmates, had several college choices, though, unlike her wealthier classmates, her decision depended largely on what colleges offer in financial aid.

There were moments when Lizbeth thought community college was all she could afford. Her weekly meetings with Akers, however, revealed other opportunities.

Babson College, on the outskirts of Boston, was one of several private colleges that topped Lizbeth’s wish list. Tuition, room and board, and supplies there come to over $60,000 a year — almost 30% more than Inglewood’s median family income.

Akers called Babson before Lizbeth was accepted. She talked about Lizbeth and explained how important a scholarship would be, and Babson has offered Lizbeth free tuition, along with living and travel expenses.

Akers does not need to be told that few Roosevelt students get that level of support. She was one of about 800 seniors there in the ‘90s, and she can’t remember even meeting a college counselor.

She says she’ll never forget, however, the junior high counselor who noticed her and made sure she got into advanced classes.

“She plucked me out,” Akers says.

And when it was time for her to move on to high school, the counselor connected her with teachers she knew and asked them to keep Akers college-bound.

“I think about that often,” Akers says. “It would have been so easy for me to get lost in the shuffle.”

ALSO

Woody Allen says he’s done hiding behind comedy

Hyperloop One succeeds at first of many much-hyped tests

From coast to coast, middle-class communities are shrinking

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.