What is a concentration camp? It’s an old debate that mostly started in California

- Share via

What’s a concentration camp — and, more importantly, who owns the term?

U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) ignited a national debate last month when she compared the government-run facilities packed with migrant detainees near the U.S.-Mexico border to “concentration camps.”

Many Republicans have pushed back in recent weeks, including Stephen Miller, a senior advisor to President Trump, who said that the comments outraged him “as a Jew.”

“It is a historical smear,” he told Fox News on Sunday, referring to Nazis. “It is a sinful comment. It minimizes the death of 6 million of my Jewish brothers and sisters.”

But this debate started long before Ocasio-Cortez tweeted about it. Japanese Americans and Jews have been arguing for decades over how and when to use the term “concentration camp” — and, in many ways, it all started in California.

The first major controversy broke out in 1972, when state officials agreed to install a plaque establishing Manzanar, the first of 10 “concentration camps” that held 10,000 people of Japanese ancestry during World War II, as a historical landmark. The decision angered many in the surrounding Owens Valley, and someone destroyed the “c” in the word “concentration” on the plaque.

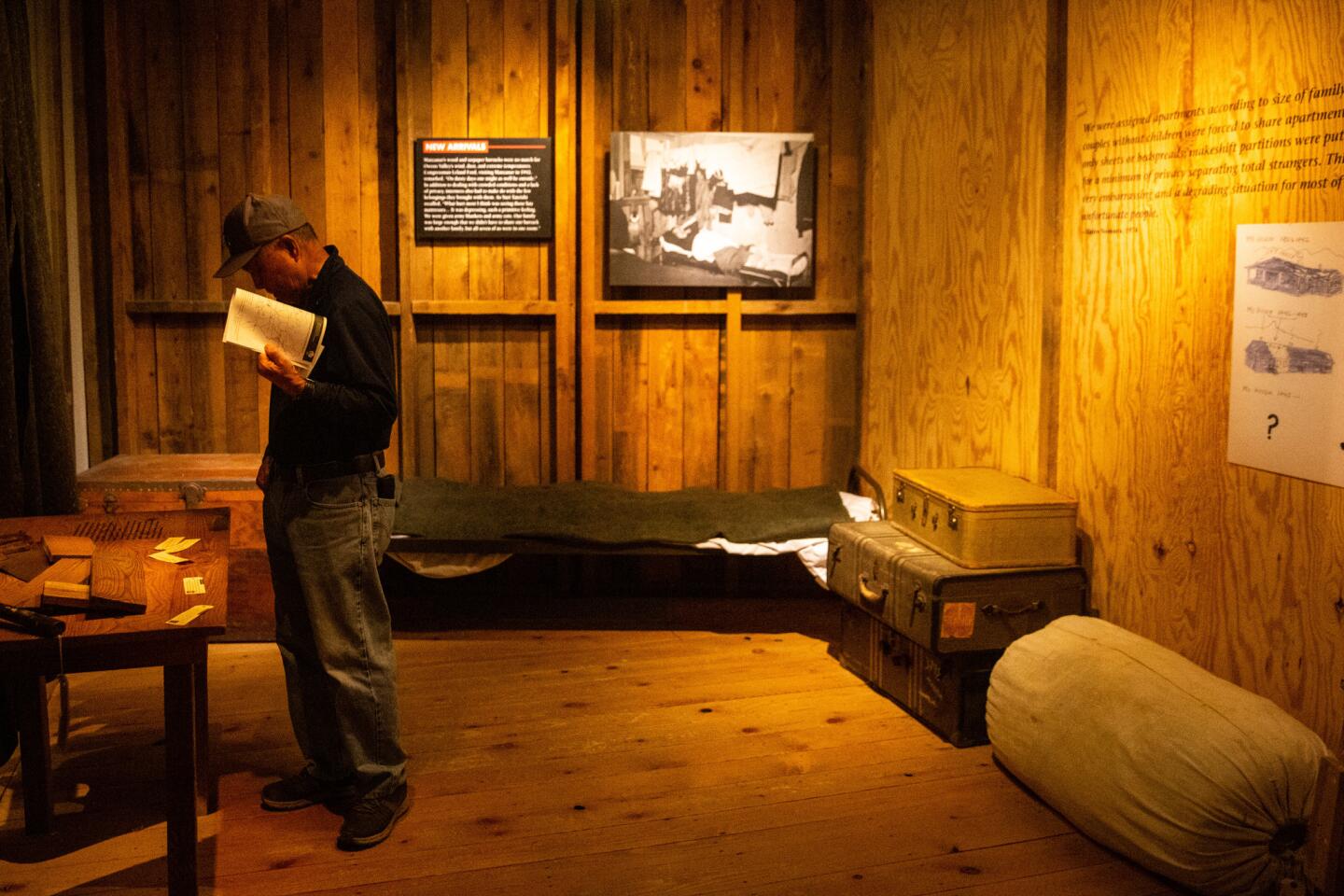

Then in 1994, the Japanese American National Museum in Little Tokyo opened the exhibit “America’s Concentration Camps,” which further explored the history of mass incarceration of ethnic Japanese during the war.

But when the museum was invited to share the exhibit at the Ellis Island Immigration Museum four years later, there was one condition: The exhibit had to be renamed, the foundation that runs the site said, because using the term “concentration camp” would offend the Jewish community in New York City.

After several meetings — and an intervention by Sen. Daniel K. Inouye of Hawaii, who made a direct appeal to U.S. Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt — Ellis Island officials dropped their demands. The exhibit opened in April 1998 with a placard that noted differences between the camps for Japanese Americans and Jews.

Karen Ishizuka, the Japanese American museum’s chief curator, recounted that history at a recent forum in Los Angeles. She said her institution never intended to imply a moral equivalency. But several community members, she said, bristled at others trying to dictate what words Japanese Americans, especially those who were incarcerated, could use to describe their own experiences.

Museum officials believed the more commonly used term, “internment camps,” was euphemistic and inaccurate, she said.

Technically speaking, World War II “internment camps” held Japanese, German and Italian nationals who were arrested on suspicion of being potentially dangerous enemy aliens and given hearings under the Geneva Conventions. That due process was not extended to the 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry — two-thirds of them U.S. citizens — who were rounded up en masse and incarcerated at other camps, including Manzanar in Inyo County.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt and other U.S. officials referred to mass detention facilities, in general, as “concentration camps,” Ishizuka said. But the War Relocation Authority, the federal agency created to manage the incarceration process, did a “political spin” and created euphemistic terms, she said.

For example, the forced removal of ethnic Japanese from the West Coast was an “evacuation.” Those removed were to be “interned,” not incarcerated. And the facilities were “relocation centers” not concentration camps.

Actor George Takei, who tweeted support for Ocasio-Cortez’s comments, told the audience at the forum that one dictionary defines them as places where “people of common heritage, race, faith or culture are imprisoned together for political purposes.”

Then he shared his family’s harrowing experience. In 1942, a few months after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor prompted Roosevelt to issue an executive order that led to the mass incarceration, U.S. solders armed with rifles pounded on the door of his family’s Los Angeles home.

Takei, then 5 years old, said the soldiers ordered his family outside to be transported to a temporary center at the Santa Anita racetrack. The family was later sent to a camp hastily built atop swampland in Rohwer, Ark.

“We were in concentration camps,” Takei said.

But Takei added that he calls the facilities “internment camps” in public talks to avoid the focus shifting to the Holocaust, as has occurred in the past.

Several American Jewish organizations have, in fact, argued that the Japanese American camps and migrant detention centers aren’t concentration camps. In a recent statement, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum said it “unequivocally rejects efforts to create analogies between the Holocaust and other events, whether historical or contemporary.”

Rabbi Abraham Cooper of the Simon Wiesenthal Center said he didn’t necessarily believe that the term should be exclusively reserved for the Nazi sites. Concentration camps feature systematic brutality and dehumanization, he said, adding that the definition might apply to China’s extrajudicial camps for millions of Muslim Uighurs who are being stripped of their language, traditions and culture.

Cooper said he sympathizes with the suffering of Japanese Americans during World War II but finds it inappropriate to call the sites that detained them concentration camps.

“To me, it offends memory,” he said. “You’re demeaning history.”

Others, however, disagree. Michael Rothberg, a UCLA professor of English and comparative literature who holds the 1939 Society Samuel Goetz Chair in Holocaust Studies, said he agrees with Andrea Pitzer, a journalist and expert on concentration camps, who defines them as places of “mass detention of civilians without trial.”

Under that definition, Rothberg said, using the term for the Japanese American camps and migrant detention facilities now along the U.S.-Mexico border is “within the realm of reason.”

Rothberg noted that the Nazis did not invent concentration camps. The Spanish used them in the late 19th century to quell Cuban opposition to their colonial rule, as the British did later to incarcerate South Africans during the Boer War.

He also said that Nazi concentration camps did not target only Jews. The Nazis began building the camps in 1933 and initially rounded up political opponents, socialists, communists and those considered “asocial,” such as gay people, Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Romani people, Rothberg said.

Only after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 did the systematic killing of Jews begin, he said. Among thousands of camps, six were explicitly outfitted with gas chambers and other means to kill Jews.

“If we reserve the name concentration camp for the Holocaust, we misunderstand the history of the Holocaust and the history of concentration camps,” Rothberg said.

As new controversy swirls over the term, Ishizuka and Rothberg stress the same thing: The name of the sites matters far less than the treatment of those they confine.

“My bottom line is that whatever you call them, the atrocities and travesties of democracy have to stop,” Ishizuka said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.