Even under adjusted funding formula, California’s poorest schools still lose out, report says

- Share via

A funding formula signed into law four years ago has mostly leveled the playing field among the state’s school districts, a report released Thursday found — but the money is not necessarily going to the neediest students.

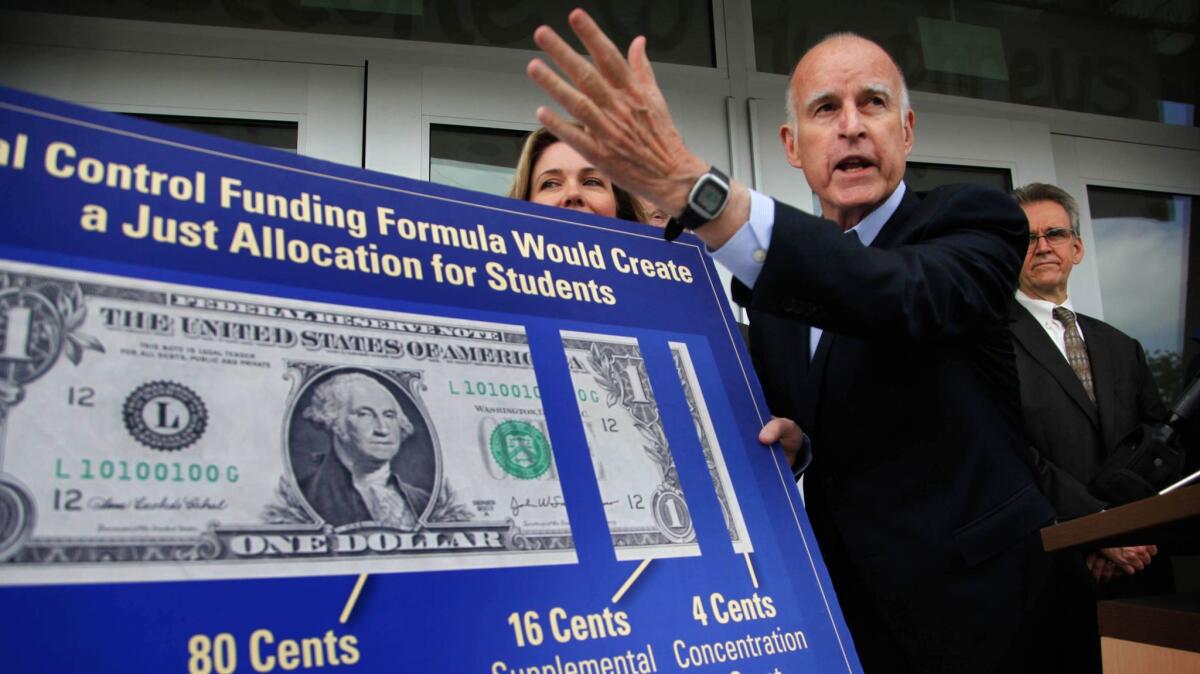

The Local Control Funding Formula, championed by California Gov. Jerry Brown, was intended to remedy educational inequities by giving districts extra money based on how many of their students were in high-needs categories: low-income children, foster youth and English learners.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. April 7, 2017An earlier version of this story stated that a law firm named Public Counsel had filed complaints against school districts regarding their use of specific funding stream. The complaints were filed by the nonprofit law firm Public Advocates.

“It is controversial, but it is right and it’s fair,” Brown said at the time.

Advocates and parents hailed the formula as progressive and called it a potential model for states across the U.S.

What the report released by Education Trust-West — an Oakland-based nonprofit that advocates for educational equity — found was that districts with the highest concentrations of poor students indeed were now receiving more funding on average than wealthier districts.

However, the neediest schools within those poor districts are not always the ones getting extra resources. “In some cases, these gaps have widened,” the report found.

In the 2004-2005 school year, the districts with the highest poverty rates received $653 less per student than those with the lowest poverty rates; by 2015-2016, the poorer districts were getting $334 more than their counterparts.

“In L.A., thousands of parents fought” for the local control formula, said Ryan Smith, executive director for Education Trust-West. “I’d hate for parents to think they fought for nothing.”

Statewide, schools now have smaller class sizes, more counselors and offer more rigorous courses than before the funding formula went into effect.

But in the 2014-2015 school year, 60% of the poorest high schools had counselors, compared with 75% of more affluent campuses. Richer high schools had three times as many librarians as poorer ones. And 70% of the poorest high schools offered physics, compared with 90% of the wealthiest ones.

In doing its analysis, Education Trust-West compared state and local revenues for the quarter of California districts with the highest concentrations of poor students and the quarter of districts with the lowest rates of such students. The researchers also examined staff assignment ratios in individual schools.

But Mike Kirst, president of the California state Board of Education, countered that schools have made progress since 2014-2015, the last year for which staffing information is available.

“We hope that EdTrust-West will follow up with a similar report in the future that draws conclusions based on the full LCFF picture,” he said in a statement.

California is continuing to work on issues of equity in education, Kirst said, pointing out that the new California School Dashboard — the color-coded online schools report card — “allows districts to enhance accountability by including student outcomes in relation to funding.”

Thursday’s report comes amid allegations that several school districts have misused extra dollars received under the new law.

The watchdog group Public Advocates has filed claims on behalf of parents in seven districts, including L.A. Unified and Long Beach Unified. The group filed the Long Beach complaint this week, alleging the district had misspent as much as $40 million in funding earmarked for targeted populations on district-wide programming this year alone.

Districts are using the extra money to plug budget holes as healthcare and pension costs increase, the Education Trust-West report found.

“Resources alone aren’t enough for us to close the achievement and opportunity gaps,” Smith said. “If you want to be an equity-based school district, you have to go beyond expenditures. It’s hard for us to determine if all districts have actually moved there.”

Because of outdated and hard-to-read accounting systems, Smith said, it’s nearly impossible to know exactly how school districts are spending their extra money.

To read the article in Spanish, click here

ALSO

State commission makes no recommendation on L.A. charter schools’ future

Most college head chaplains are Christian. At USC, a Hindu leads the way

Obama administration Education secretary endorses Gonez, Melvoin for L.A. school board

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.