The problem with slut shaming in schools

Angel Fabre and James Salazar are students at L.A.’s Ramon C. Cortines School of Visual and Performing Arts. After a dress code incident, they started a petition and organized a rally to protest sexist dress codes in their high school.

- Share via

Mary “James” Salazar and her mother have always watched “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit” together. That’s where they first encountered slut shaming. Victims on the TV show were blamed for their own sexual assault, or judged because of the clothes they’re wearing.

Slut shaming wasn’t a phenomenon that either expected James to encounter at school. But James, then 16, says she was kept out of class for most of a day in October because she wore a red spaghetti-strap dress, during a Los Angeles heat wave. A counselor told her she wouldn’t be able to go back to class unless she put on a sweater. James said staff pointed out that her bra was showing, and told her that her clothes were too revealing and distracting.

James, now 17, says she told them that was sexist. She refused to change her clothes.

“I was there to learn,” Salazar said at the anti-slut-shaming rally she and a friend organized at the school a few weeks later. “We should be able to express ourselves how we want to.”

What is slut shaming, anyway?

Slut shaming is the practice of punishing or making character judgments about people, usually girls and women, based on their sexual activity or on assumptions about their sexual activity. Those assumptions can be based on what they wear, what they look like or rumors about them.

Slut shaming starts early. A nationally representative 2011 survey from the American Assn. of University Women found that slut shaming is one of the most common forms of sexual harassment that students in middle and high school face. A third of all students experienced “having someone make unwelcome sexual comments, jokes, or gestures to or about you” in person; 46% of girls experienced it and 22% of boys.

More than a fourth of all girls and 13% of boys experienced “being sent unwelcome sexual comments, jokes, or pictures or having someone post them about or of you” online.

Experts say slut shaming can happen if dress codes and their enforcement are skewed toward making sure girls’ clothing isn’t “distracting” to boys, or in the rumors that students spread about each other. Beyond clothing, activists say, slut shaming influences the way people think about girls’ responsibility to prevent their own sexual assault.

The term “slut shaming” is actually redundant because “slut” has almost always had a negative connotation.

“It’s designed to insult women who have sexual agency or experience or want sexual pleasure,” said Shira Tarrant, a Cal State Long Beach professor who researches gender and sexual politics. “We don’t even have a word to describe a happy, joyous, sexually active female.”

Do boys get slut shamed?

Not really. “Boys do not encounter, for the most part, slut shaming the way that girls do,” said Catherine Hill, vice president for research at the American Assn. of University Women.

Boys face sexual harassment and bullying in schools, but most often for things that undermine traditional notions of masculinity — boys who are overweight or not athletic are targeted more, and they are often called gay as an insult, according to Hill’s research.

For girls, slut shaming includes being the subject of rumors, getting their pictures posted and “pointing out basically that girls are sexual beings,” Hill said. That has a negative connotation, while boys are less likely to see sexual rumors about themselves as harmful to their reputation.

How do these incidents affect students?

James says the dress code incident kept her out of classes for the day, disrupting her education. She has since left the Ramon C. Cortines School of Visual and Performing Arts, and is finishing high school through an online homeschooling program. She was considering leaving the downtown campus before the incident, but the dress code violation is what convinced her mother that it was necessary, said Luisa Salazar, James’ mother.

In other schools around the state, students have faced similar consequences because of dress codes. In Central California, a teen just won the right to wear a shirt that says “Nobody knows I’m a lesbian” to school. According to the lawsuit, an assistant principal said the shirt was “promoting sex” and an “open invitation to sex.”

Is slut shaming a kind of bullying?

Yes. “It’s gendered bullying,” Tarrant said. “It’s sexualized bullying.”

Tarrant hopes that if people recognize slut shaming as a form of bullying, they might be more likely to avoid it.

For students facing slut shaming, the long list of effects can include “depression, suicide, alienation, self-hatred, sexual fear, sexual recklessness,” she said. All of those affect a student’s ability to concentrate and ability to succeed in a classroom setting.

A 2010 UCLA study found that students who were bullied in middle school earn lower grades than their peers.

Not only is it bullying, slut shaming is a form of sexual harassment, Hill said.

Middle and high school students who had been sexually harassed didn’t want to go to school, felt sick, had a hard time studying and sleeping, got in trouble at school, stopped playing a sport or activity and even stayed home from school, according to the AAUW report.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

But don’t we need dress codes?

There is mixed research about how dress codes affect student performance, Hill said.

Dress codes help students focus on the classroom and learning rather than on each other and their clothing, said Earl Perkins, the assistant superintendent overseeing school operations in L.A. Unified.

“If young men come to school with their pants hanging down … and wife beaters on, all my females are paying attention to them,” Perkins said. “If all my girls come to school with midriffs showing … all my boys are focusing on them.”

Perkins does not think either the dress codes nor their enforcement are sexist, he said.

A problem with that logic is that girls are sold clothes that cover less of the body than typical boys’ clothes, so they might be more likely to be targeted, said Terri Conley, a women’s studies professor at the University of Michigan.

That’s a function of fashion, media and the ingrained societal expectation that women’s bodies are more sexualized than men’s, Conley said. So girls buy short shorts and lower-cut shirts because that is what is available to them, and then are punished for being provocative.

“And so it really feels like the situation is rigged,” Conley said.

It is true that in middle school and high school, adolescents are exploring their sexuality and how to express it, which includes clothes, Hill said. But that doesn’t mean every item of clothing is meant to be sexual or attract male attention, she added, and it doesn’t mean that girls should be held responsible for being distracting to boys.

How is slut shaming related to rape?

The idea that girls should avoid wearing certain clothing because boys might be affected is not only flawed but dangerous, Tarrant said.

The idea that women are responsible for the reaction of men, or that men are unable to control themselves, leads to blaming victims after they’ve been sexually assaulted.

“The message being that boys can’t help themselves … that’s a really dangerous one to send,” Tarrant said. “We just know that’s not true.”

After a woman is sexually assaulted, people often ask what she was wearing or about her sexual history, a suggestion that she attracted the assault by wearing clothes that were revealing, or that she made herself available by having sex with other people.

L.A. Unified School District tried to use a girl’s sexual history to blame her for her own sexual assault in a civil case, for example. An appellate court ruled that the school district could not use that argument, and a new state law in California prohibits such arguments.

What are people doing about it?

Upon hearing about James’ situation, her classmate and friend, Angel Fabre, decided to start a movement at the school. She started an online petition for the “separation of dress and education,” and held a rally to bring attention to slut shaming in dress code enforcement.

“This dress code is promoting the idea … that I’m inappropriate and I should be ashamed of myself,” Angel, 17, said at the rally.

L.A. Unified’s central area superintendent, Roberto Martinez, said he would ask principals at about 160 schools he oversees to reexamine their dress code policies after the Los Angeles Times asked about the incident with James and the rally.

Schools could also do a better job teaching students about respect and consent through gender studies classes and lessons on violence against women, Martinez said.

The movement to address slut shaming and dress codes goes far beyond L.A. Students in Canada held a crop top day last year after they were told that they couldn’t reveal their midriffs, and students in Illinois held a similar event to assert their right to wear leggings in 2014.

After a police officer in Toronto told women they shouldn’t dress like “sluts” if they didn’t want to be assaulted, women in Canada and the U.S. began organizing “SlutWalks” to protest victim blaming, including in Los Angeles.

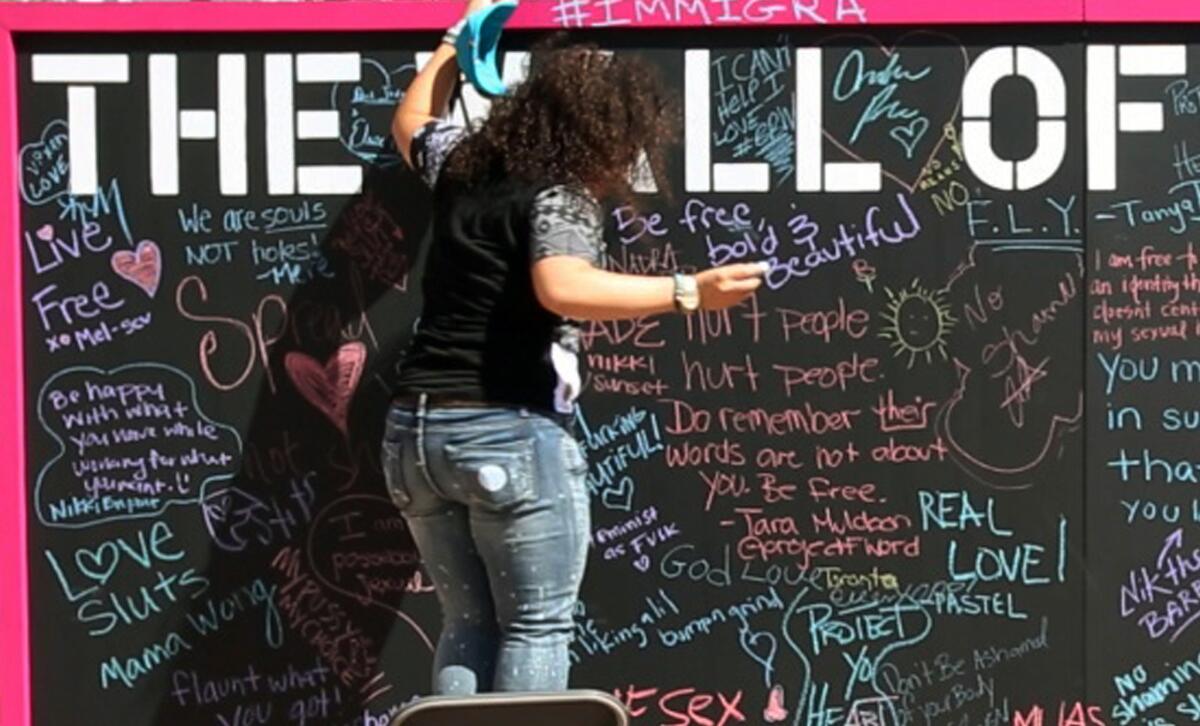

People write on The Wall of No Shame as hundreds gathered at Pershing Square for SlutWalk, an anti-slut-shaming event put on by model Amber Rose in Los Angeles on Oct. 4, 2015.

Schools and parents also need to have conversations with student about sexual consent and respect early, Tarrant said, before the slut shaming has a chance to start.

L.A. Times staffer Lisa Biagiotti contributed to this report.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

MORE EDUCATION COVERAGE

Girl can wear ‘Nobody knows I’m a lesbian’ T-shirt at school

Court’s move to give two nonprofits access to students’ personal data ignites privacy debate

Why only 19% of Cal State freshmen graduate on time -- and what lawmakers aim to do about it

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.