‘Go destroy them,’ artist says of his paintings

Nader Haj Kadour painted hundreds of portraits of Syria’s Assad family. Now rebels are tearing down and ripping apart the works he spent his career creating.

- Share via

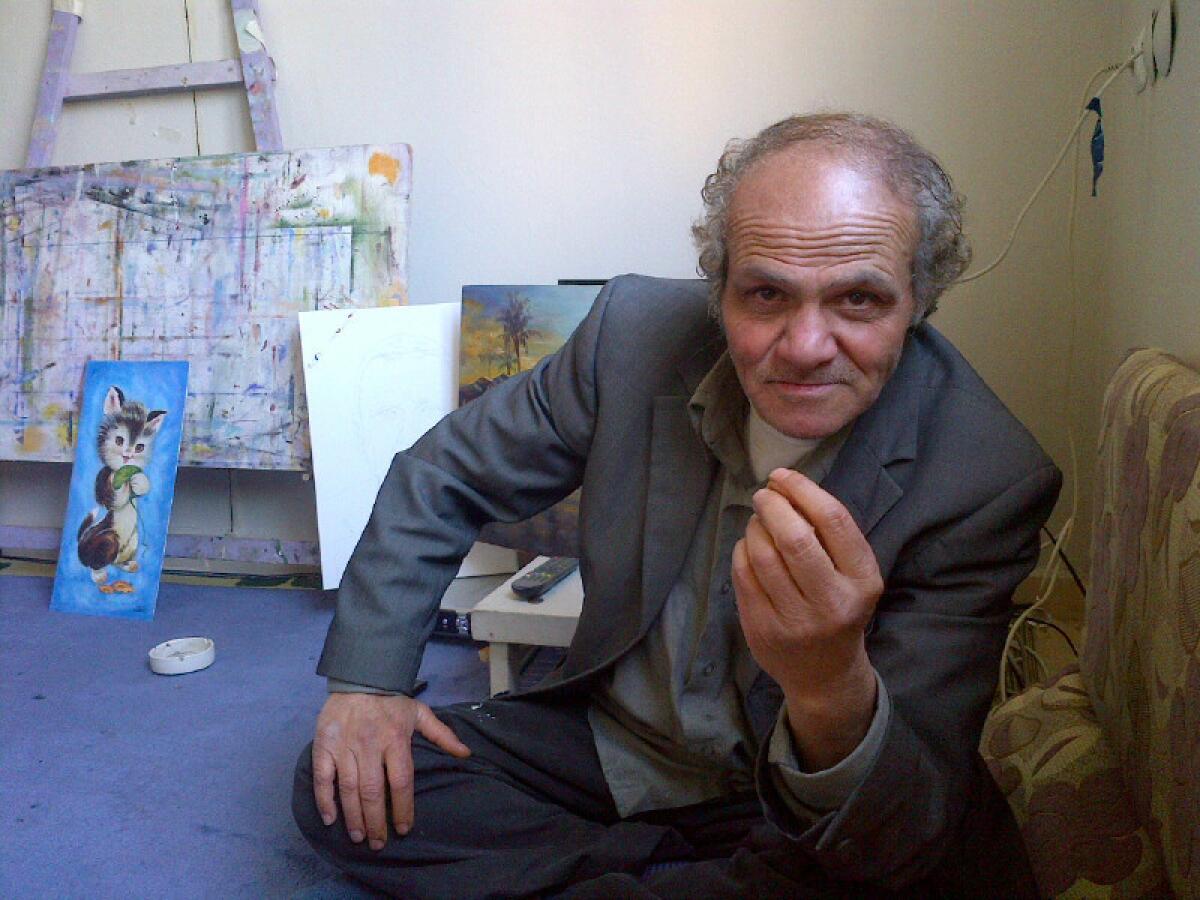

The classically trained Haj Kadour is happy to discuss the finer points of painting cartoon characters but prefers not to dwell on the many portraits he was asked to produce for Syria's ruling Assad family. (Raja Abdulrahim / Los Angeles Times) More photos

On the second floor of a nursery school in a Turkish border town, artist Nader Haj Kadour preferred talking about painting butterflies than painting Syrian President Bashar Assad.

The classically trained Syrian artist pointed to a recently completed yellow and purple cartoon, part of the growing acrylic garden along the walls of the school in this town crowded with refugees. Then he delved into the finer points of painting for a young audience.

"See this butterfly? If you paint it in a classical style, you haven't done anything for the child," he said.

Haj Kadour was less eager to speak about his main subject for the last four decades: the late President Hafez Assad and, later, his son Bashar.

Their faces have dominated walls, storefronts and car windows all over Syria, a visual declaration of loyalty to the dictators. Their images — sometimes partially hidden behind sunglasses, other times in military uniform but always stern and slightly foreboding — were the ubiquitous reminders that Big Brother was watching.

Haj Kadour painted hundreds of the portraits.

"We don't need to dwell on that," he said.

When the uprising began more than two years ago and government control of his town in northern Syria began to slip, he was at last free to explore the nonpolitical subjects he favored.

"I wanted to paint landscapes or paint animals, but the requests for the president's portrait were constant," said Haj Kadour, whose thinning brown and white hair sticks out in tufts like stuffing popping out of a pillow.

Now, as the revolt against Assad continues, the 66-year-old artist has seen the portraits he spent his career producing torn down and ripped apart.

Once, local opposition figures came to his house in Syria and apologized for defacing his paintings.

"I told them, 'You don't have to get my permission; go destroy them.' "

Haj Kadour began his two years of compulsory military service in his early 20s on the outskirts of the capital, Damascus. All draftees were asked whether they possessed any special skills, and he volunteered that he could paint and do calligraphy.

The army general who oversaw the base assigned him to the officers' garden and would regularly bring Haj Kadour canvases and supplies. The general would request landscapes to adorn the offices and once asked for a replica of the "Mona Lisa."

Haj Kadour has only recently begun drawing inspiration from the Syrian uprising. His most recent painting, shown here in an undated photograph provided by his family, is of a woman sporting both the Syrian opposition and Turkish flags. (Handout) More photos

In 1970, while Haj Kadour was still serving, Syrian President Nureddin Atassi was overthrown in a coup by the commander of the air force, Hafez Assad.

Those in the military were eager to show their support for the new president. The general brought Haj Kadour a photo of Assad and told him to paint a portrait for display during a speech by the new president at the Justice Palace.

"When they saw that I was painting the president and making him look better than he looks and painting with emotion, they began coming to my army studio and requesting my work," he said.

After Haj Kadour was discharged, the requests continued — from government and ruling Baath Party institutions, police stations and various organizations or businesses that wanted to prominently show their fealty to the president. The head of the country's notorious secret police once commissioned a portrait from him.

The paintings also served as their own bribery currency.

Everyone was part of the facade of allegiance to the Assads — or paid the price.

A person hoping to curry favor with or cut corners at a government agency would bring along not food or gifts, but a presidential portrait, Haj Kadour said.

"They made them gods," he said.

When Bashar Assad inherited the presidency after his father died in 2000, Haj Kadour, like many Syrians, was optimistic about the London-educated ophthalmologist.

There were early promising signs, such as an unofficial ban on displaying the younger Assad's image publicly and ubiquitously. Soon though, the old practice reemerged and the portrait requests began anew. Until the uprising began in March 2011, Haj Kadour was fielding an average of two requests a week for Bashar Assad's portrait.

"When I was making money painting the president, I wasn't happy about it," he said. "I had to. If I said no, the security officers would say, 'Why don't you want to paint the president? That means you are against him.' "

Members of the opposition don't blame Haj Kadour for his portraits. Everyone was part of the facade of allegiance to the Assads — or paid the price.

He has no appreciation for art."— Nader Haj Kadour about Syrian President Bashar Assad.

"No one held any grudges against him for painting Bashar and Hafez," said Adham abu Husam, a prominent opposition activist in Haj Kadour's hometown, Benish.

Although he loves his homeland, Haj Kadour said it felt like a grave under the Assads. He said he used to feel as if he could breathe freer whenever he went abroad to study or do a commissioned piece.

About five years ago, after he painted a 10-foot-tall portrait of Assad that hung in the city of Idlib, he was summoned to the presidential palace in Damascus. He was asked to paint 20 more portraits to be hung in the rooms of Republican Guard officers.

Each day, Haj Kadour was told he would meet the president, but he never did.

He leveled what, at least for him, was a serious charge against the Syrian leader: "He has no appreciation for art."

Seven months ago, Haj Kadour and his family fled Benish. He, his elderly mother and his brother's family have settled in two adjacent apartments in Reyhanli, 15 minutes from the Syrian border.

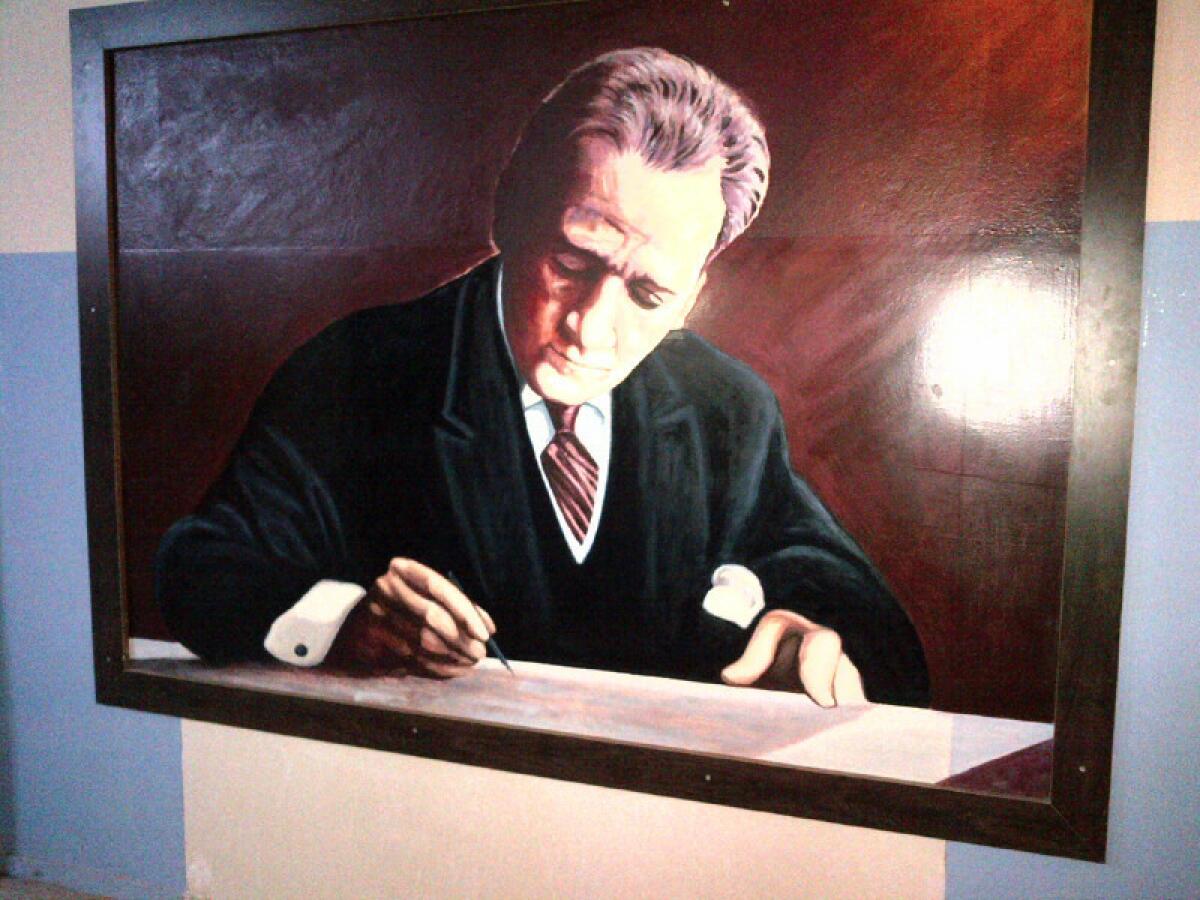

Haj Kadour's painting of Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey, adorns a wall at a vocational high school in Reyhanli, Turkey. There is a waiting list of Reyhanli schools that want to hire the artist, said Necmetin Yumusak, the school's principal, who called him a "maestro." (Raja Abdulrahim / Los Angeles Times) More photos

In his small bedroom, sketches of horses, rabbits and landscapes line one wall and the rest of the space is taken up by a few thin mattresses and art supplies scattered on the floor. The ceiling is covered in mildew in an almost abstract pattern, as if Jackson Pollock had flung fungi rather than paint on a canvas.

Haj Kadour, a thin man whose oversized and sometimes paint-specked clothes flutter around him, moved around his room for more than an hour looking for the right paint.

His deep-set eyes wandered more often than they focused. The stubble on his face indicated an inattentive shaver, in keeping with his conversation: One thought quickly merged into another and then another, and at times he paused midsentence and stared ahead for several seconds as his mind went elsewhere.

"Art was an addiction and I submitted," he said. "I raised the white flag."

When antigovernment protests broke out in his hometown, Haj Kadour began drawing the president in a different way.

He helped activists draw caricatures of both Assads, images that could have landed him in jail or worse: Bashar with enormous ears and no chin, Hafez with a sharp nose and chin and also comically large ears.

Before he began painting the walls of the nursery school here, the only art on display was rudimentary paper mushrooms expressing a range of emotions and austere, sometimes bloody prints depicting important events and figures in Turkish history.

At a nearby vocational high school, Haj Kadour completed three murals in less than a month, including one of modern Turkey's founder, the late President Kemal Ataturk. There is a waiting list of Reyhanli schools that want to hire Haj Kadour, said Necmetin Yumusak, principal of the vocational school, who called him a "maestro."

Syrian artist Nader Haj Kadour completed three murals in less than a month at a vocational high school in the Turkish border town of Reyhanli, including this landscape. The artist poses here with his work. (Raja Abdulrahim / Los Angeles Times) More photos

"He likes to paint and he's not after the money — he wants the creation," Yumusak said.

"Even after the war ends, we're not going to let you go back to Syria," he told Haj Kadour. "We'll find you a Turkish wife and you'll stay here."

On a rainy Sunday night, Haj Kadour was at the school taking advantage of the empty halls to work. He examined a recently completed mural of a mountain landscape.

He stepped back from the wall.

"The fluorescent light above the landscape — the principal put it up — the way he put it up was wrong, it shows all the blemishes in the wall and hides the details of the painting," he said. He added, as if in a museum and not a chilly high school in a rural village, "I told him the lighting needs an engineer."

When Syrian rebels seize government buildings or military bases, one of their first acts — often videotaped and posted online — is to tear down the presidential photos and paintings.

Assad family portraits torn down

In a video from 2011, a mob of men and young boys swarm a toppled sign with portraits of President Bashar Assad, his late brother Basil and their father, Hafez.

In one video from Benish on April 20, 2011, a mob of men and young boys swarm a toppled sign that welcomed people at the eastern entrance of the town. They take turns climbing atop one of the three portraits — of Bashar, his late brother Basil and their father — delivering punches and kicks, before jumping off and letting someone else have a go.

Sometimes Haj Kadour would watch the videos of his paintings being destroyed. He said the destruction of what amounts to his life's work didn't sadden him.

Even the photos he had of those paintings are gone. When the army stormed Benish and raided homes, soldiers stole his computer.

Haj Kadour thought his years of venerating the presidents with his paintbrush would protect him and showed the troops certificates he had received from the government.

"They said, 'We don't care.' "

More great reads

Battle rap pits Stalin against Rasputin (and more)

After fleeing polygamist sect, boys face a new world

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.