Great Read: Not bound by history, L.A.’s Caravan Book Store continues to turn pages

- Share via

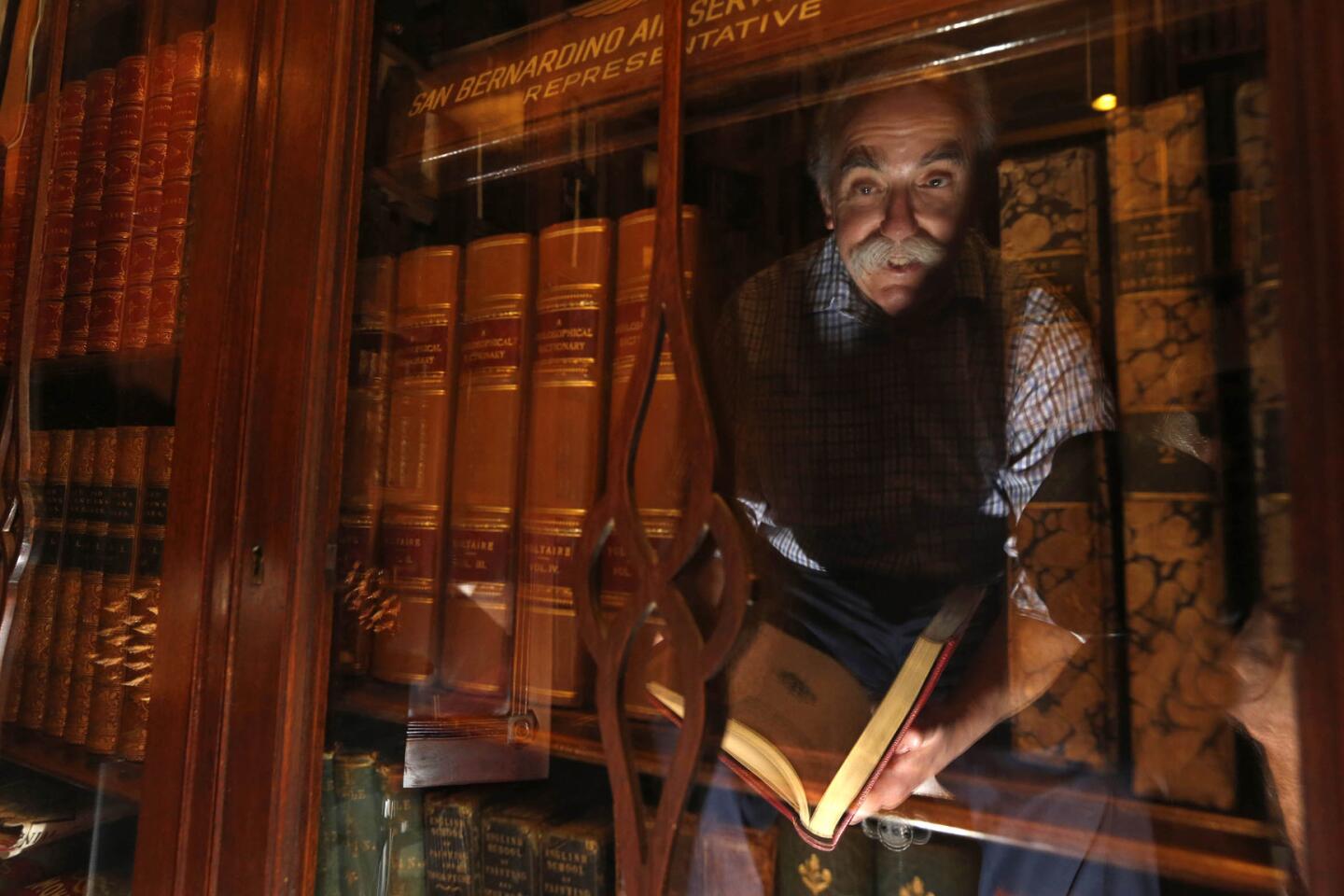

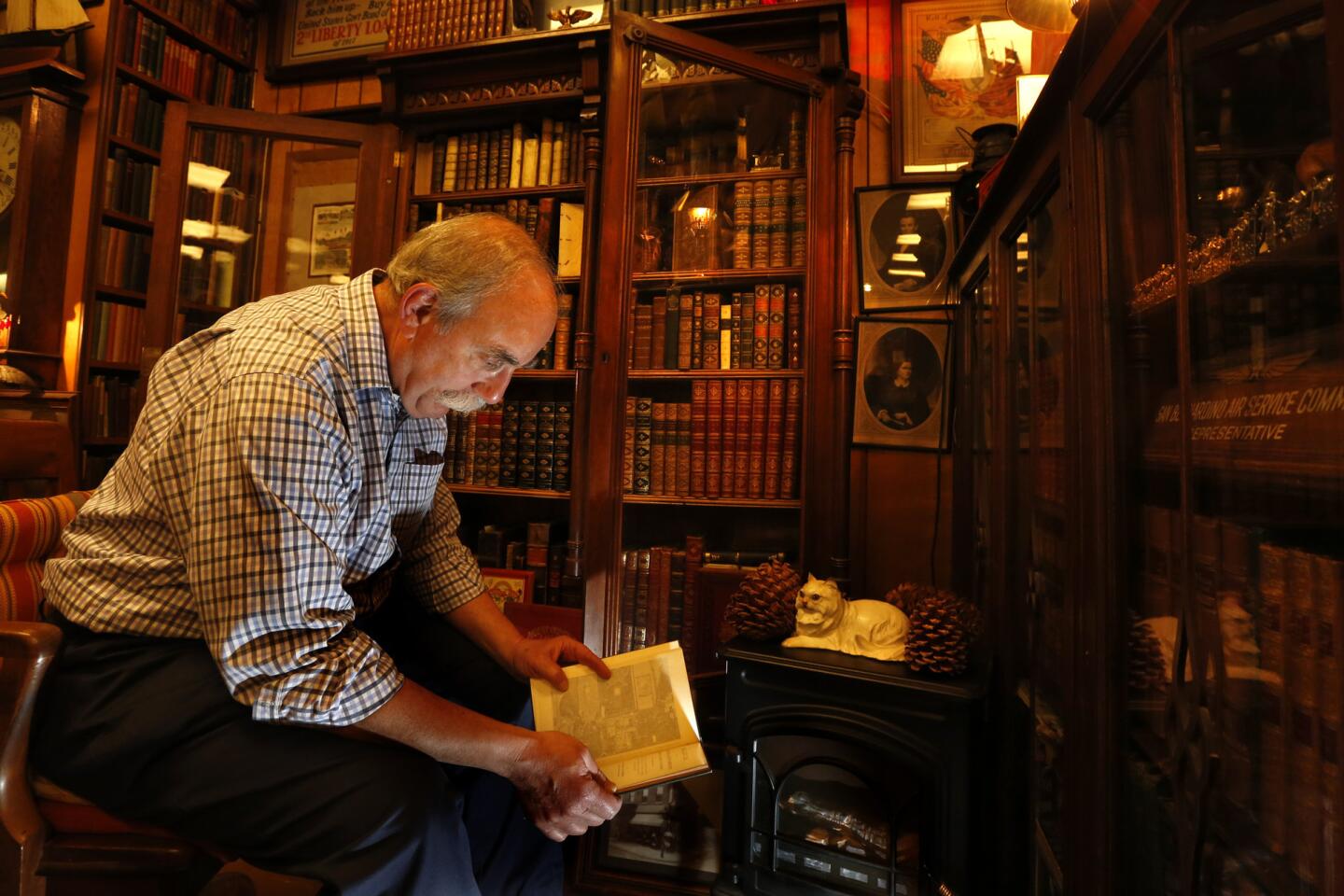

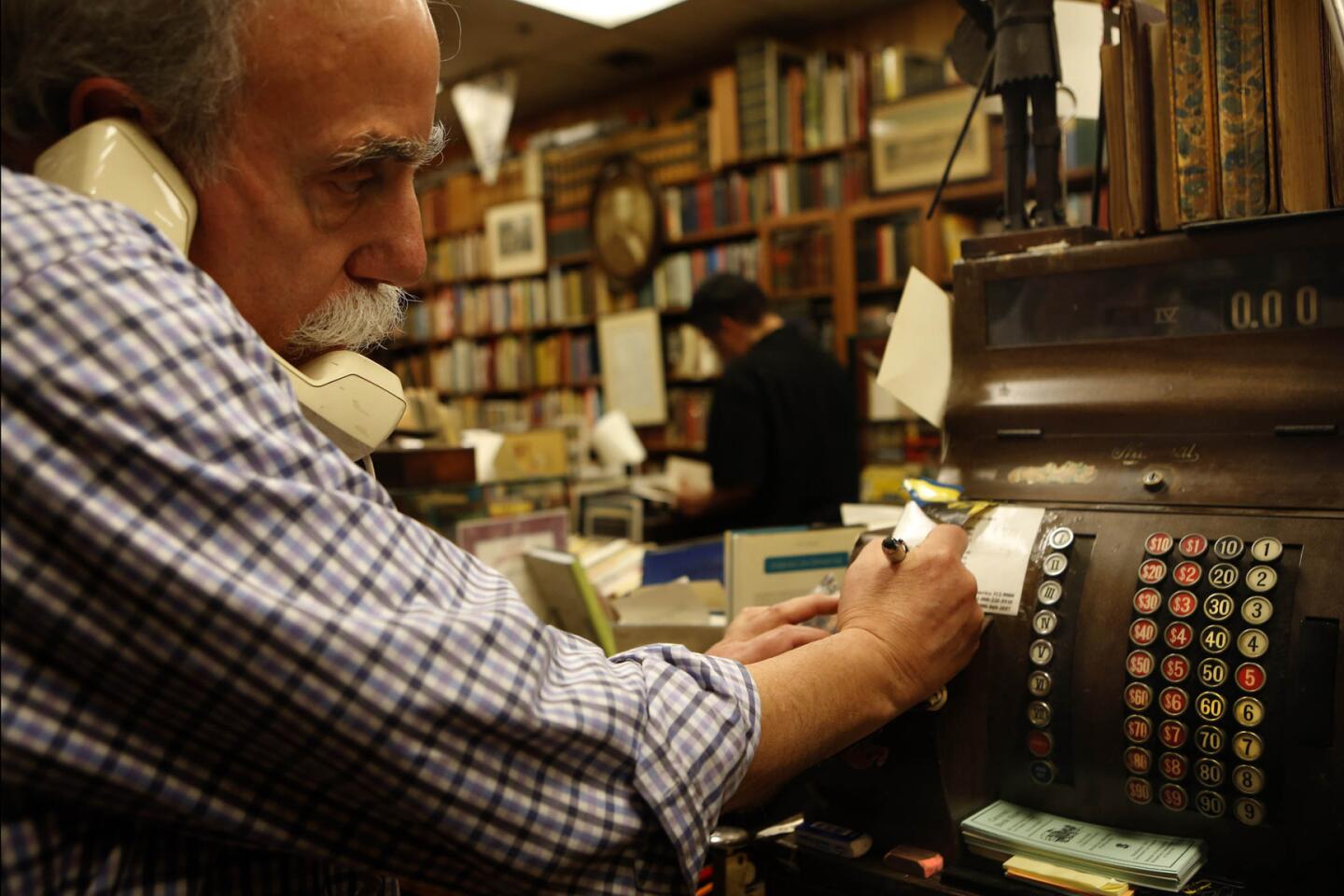

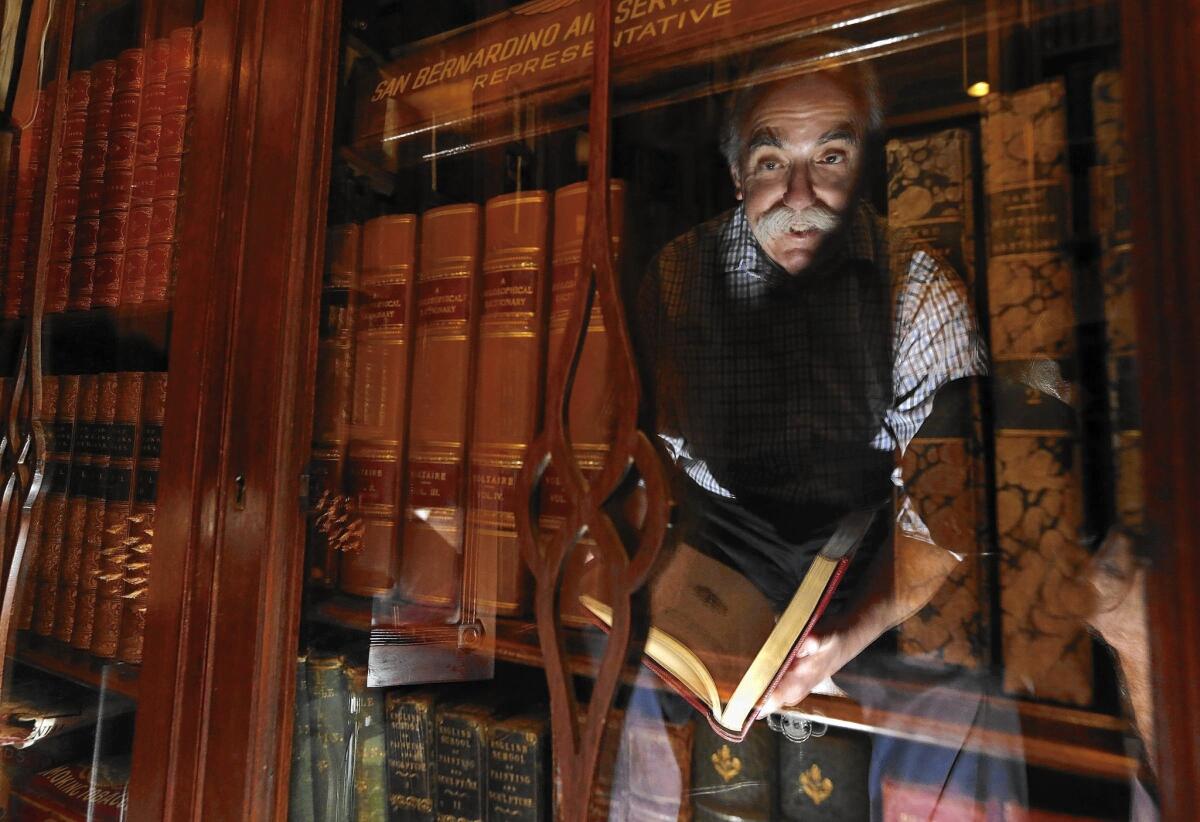

A shuffling step carries Leonard Bernstein onto Grand Avenue. The pilasters and garlands of the PacMutual Building rise above him. Nearly 70, a balding man with a gray cattle-catcher mustache, he finds his keys and stoops to the lock in the threshold.

Two bells tied to a red ribbon jingle as the door swings open. He punches the alarm code, hits the lights and raises the amber screen that shields the window display.

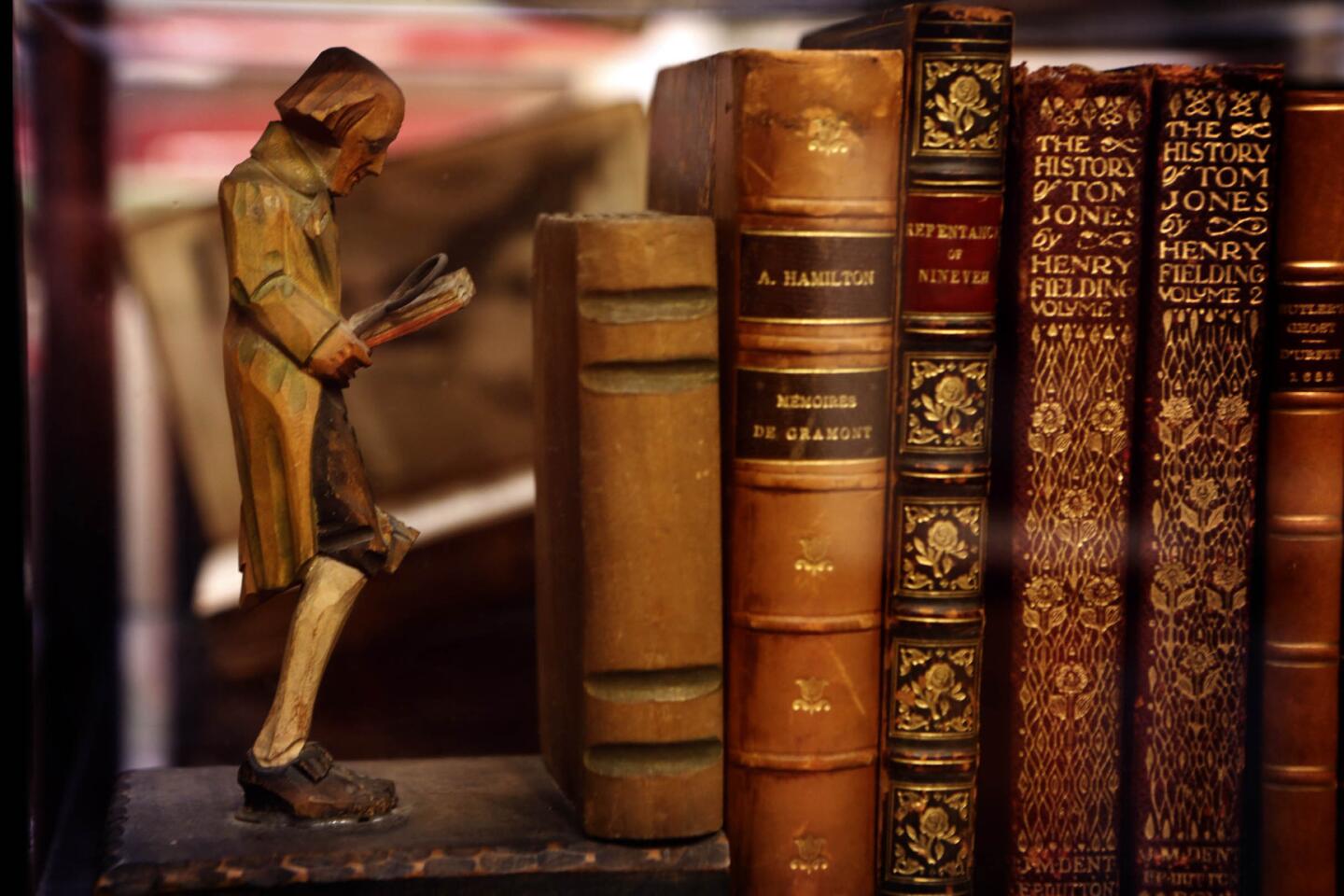

Late morning light brightens the casual clutter of books and sailing ships, trains and street signs, Civil War curios and Wonderland chess pieces.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

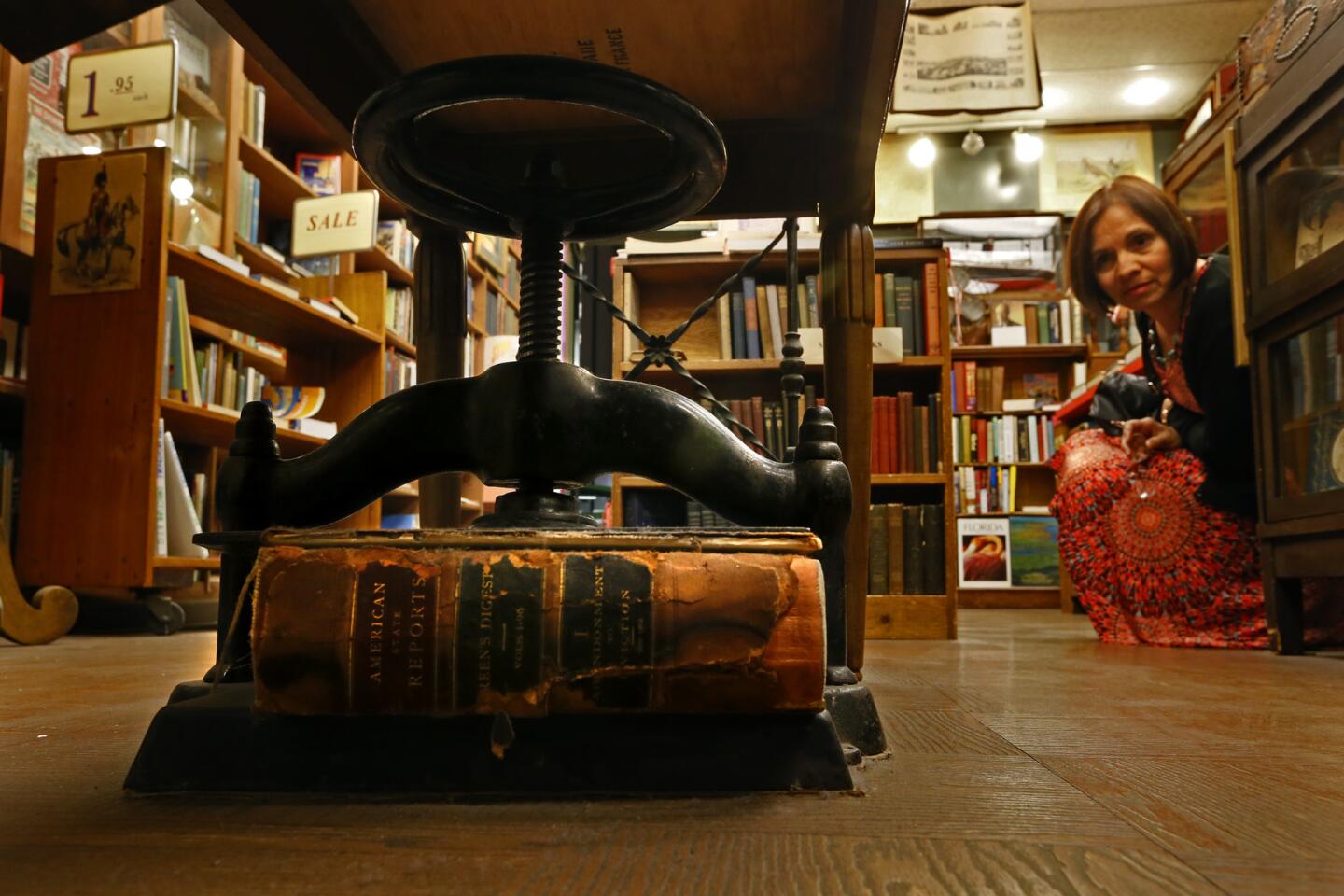

Caravan Book Store is open. A raft in a downtown awash in rising rents and fast entertainment, it is a refuge where pages matter more than page views, Gutenberg more than Google.

Old and new, curious and rare, reads the sign above the street.

There is a musty tang in the air. Bernstein follows a narrow aisle between display tables and glass-fronted cabinets to his desk in the back of the shop.

His chair gives a familiar creak.

Caravan won’t be found on the Internet. It has no website, and the store’s Instagram presence, a fleeting nod to the digital world, is a mere echo of its analog insistencies.

To linger here is to walk with Cortes toward Teotihuacan, drift with British surveyors down the Congo River, stroll through the palaces of Los Angeles’ Gilded Age or revel in Carl Sandburg’s muscular lyricism.

Hog Butcher for the World, he wrote, Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat …

::

Between these bindings of cloth and calf, dust jackets and gold leaf lie the ideas, memories, fantasies and dreams that have occupied Bernstein since he was a child.

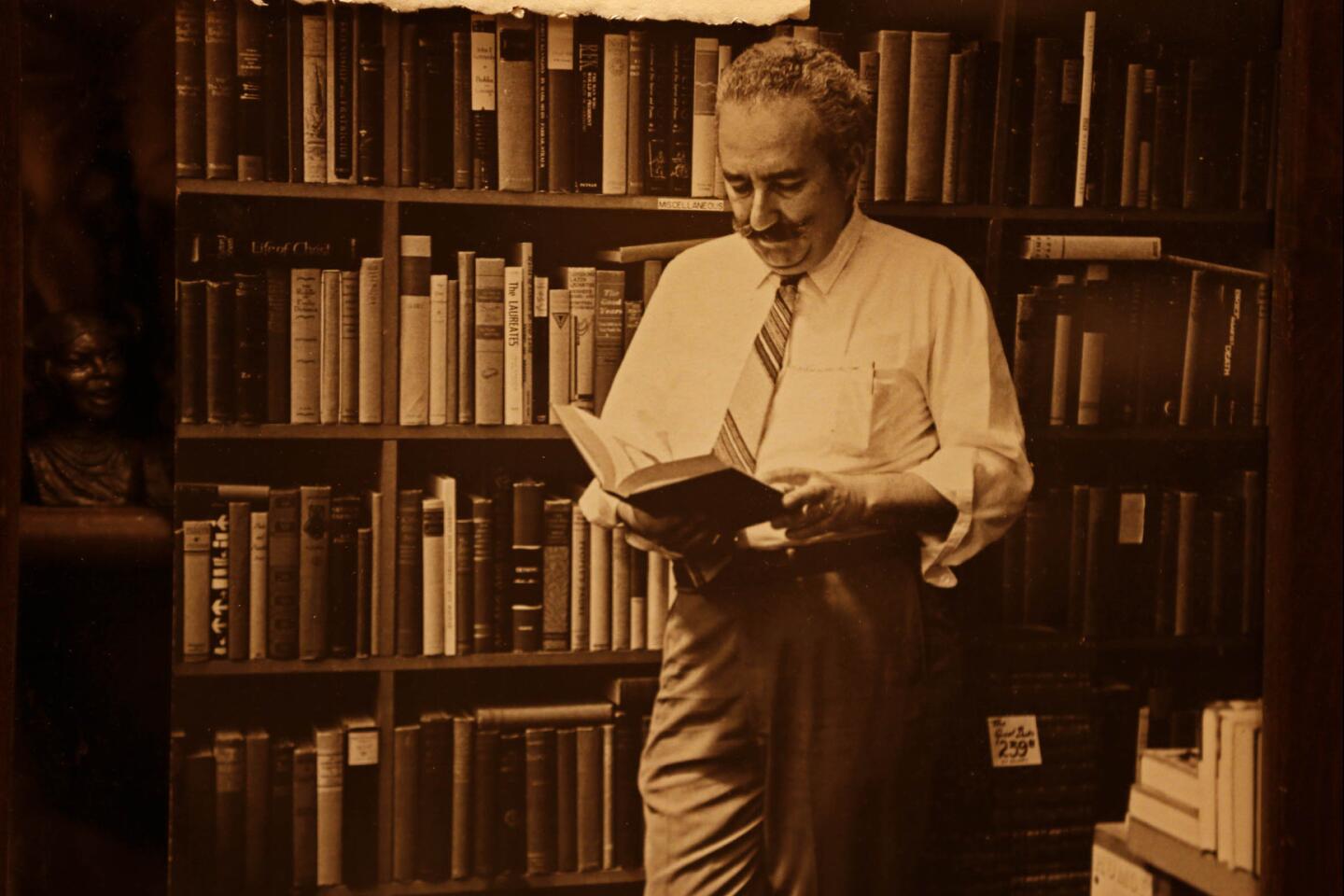

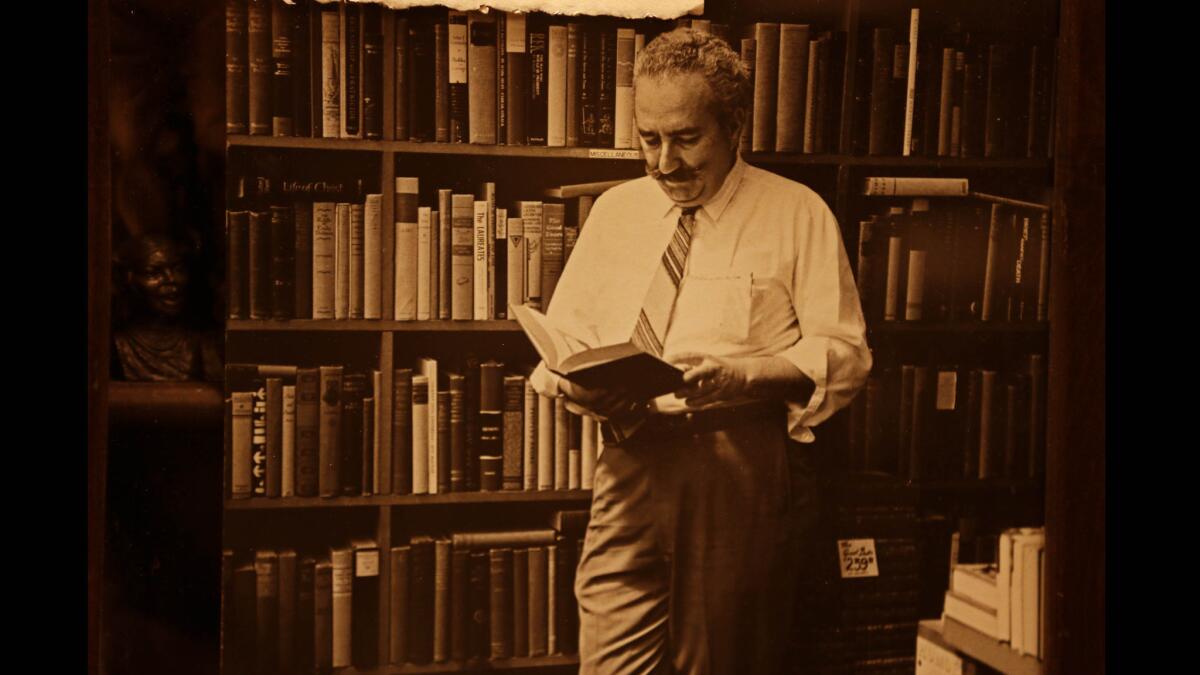

His parents opened Caravan on May 15, 1954. Some thought Morris Bernstein crazy. But he and his wife, Lillian, didn’t like being apart during the day.

His mother-in-law suggested they carry a line of ties, just in case.

They tried to have a plan, stocking at first a selection of Bibles — Biola University, with its famous “Jesus Saves” red neon, was just up the street — but Bibles didn’t sell.

An undated photograph of Morris Bernstein, who founded Caravan Book Store in 1954. Some thought him crazy. But he and his wife, Lillian, didn’t like being apart during the day.

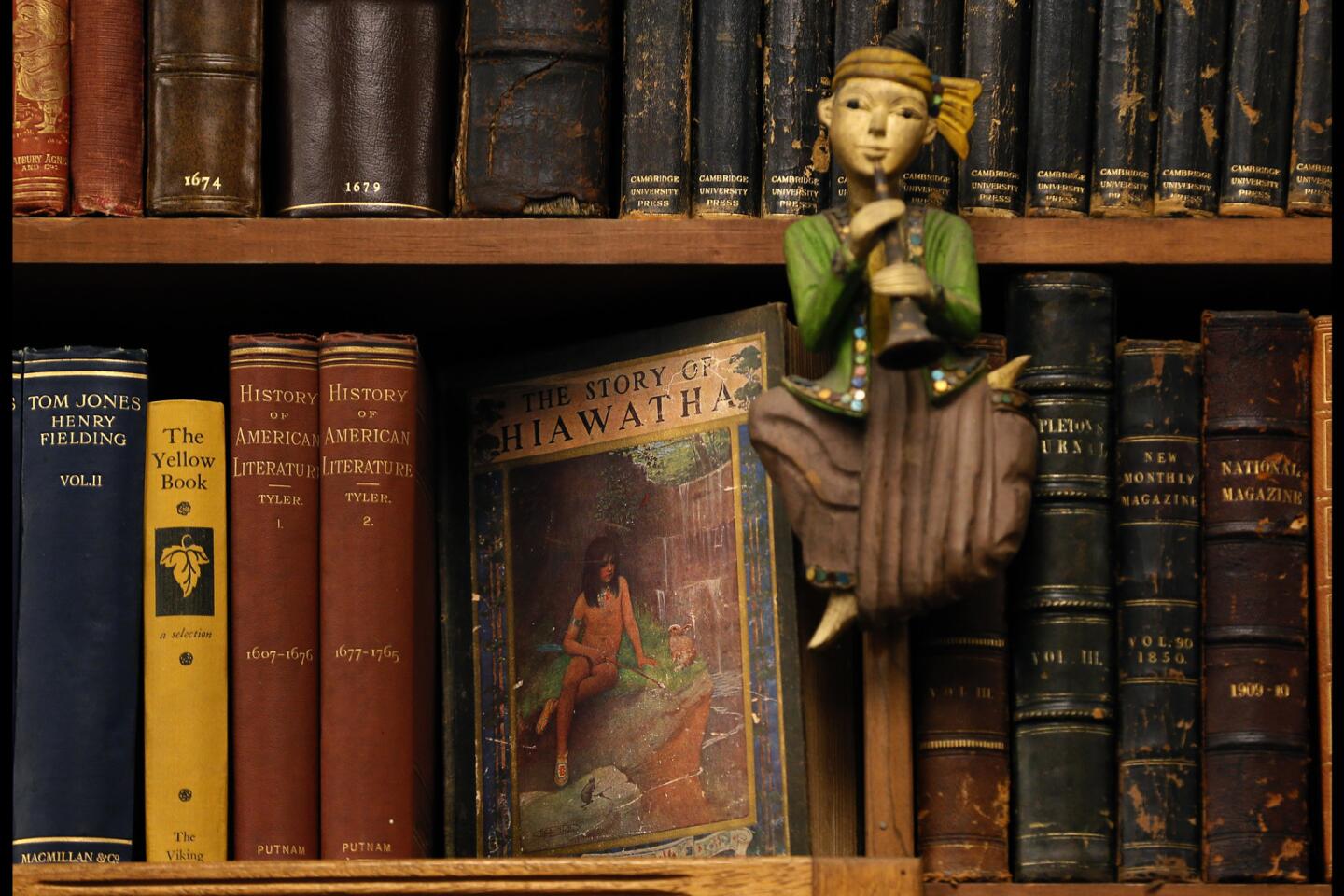

So they focused on the unusual and unique, the far-reaching and exotic, the titles that suited the store’s name, with a special niche for books on Los Angeles, a niche that has grown as the city has changed.

Gone are the destinations of his childhood, the pet store on Hill, the soda fountain on Grand, the hardware store on Main.

Today, a half-block away, a driveway leads to a subterranean parking lot. This was where Caravan originally stood, he says, along with an airline agency, a shoe store, a florist and a card shop. Then it became a German bank. It failed. Now it’s lofts.

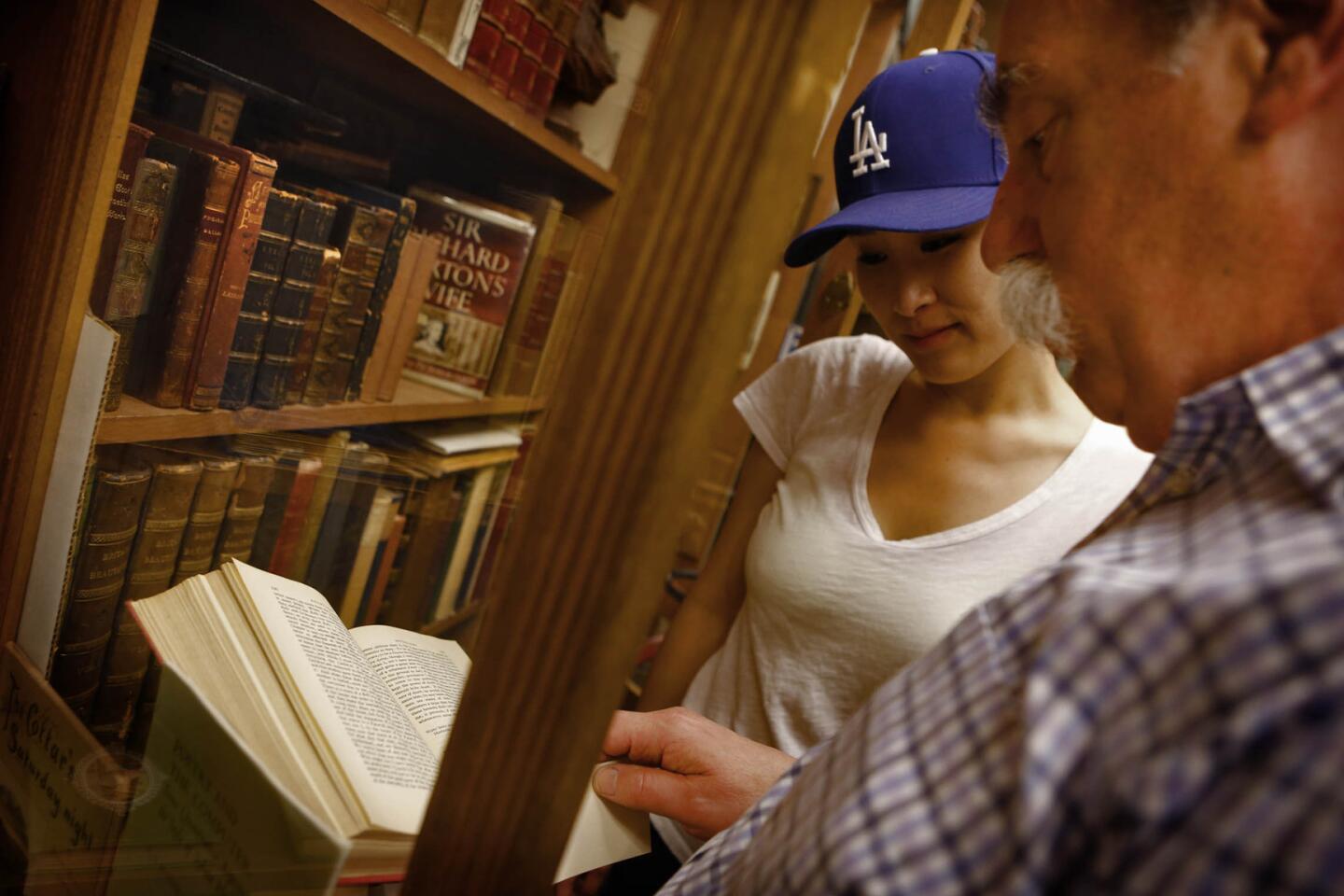

A bell chimes. A woman wanders in. Bernstein nods and leaves her be, a well-practiced manner respecting the privacy of the browser. He knows he is a mystery, this old man in this old store.

But Caravan, he insists, is no museum dedicated to books, no antiquity stuck in amber. Its vitality comes from everyday customers and their passions, both commonplace and esoteric.

He is not as concerned about the incursions of the Internet and books going out of fashion as he is about readers becoming less curious, less imaginative, less democratic in their tastes.

Outside traffic streams by, the wail of a siren, the pinch of rusty brakes, words of an idle conversation. Smoke from a cigarette wafts in from a nearby valet station.

Ask how he makes ends meet, and he tells the riddle of the centipede. How does it walk? Only without thinking about it. The recent recession wasn’t easy, he admits, but neither were the downturns in the 1980s and ‘90s. The riots too were hard, earthquakes are hard, and crime is never good.

::

Once downtown had its own Booksellers’ Row, a dozen stores along 6th Street: Jake Zeitlin’s, Dawson’s, the Abbey, the Argonaut, Holmes’. Now they are gone.

He can’t explain his longevity.

He tried selling new books, but the business of new books isn’t as fun. Shipments arrive with prices fixed. Better to hold on to this more ancient commerce, this legacy-keeping that has brought the world to him.

Alfred James Munnings’ equestrian prints.

John James Audubon’s “The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America.”

An 1896 illustrated guide for tourists to the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway.

A first edition of Boswell’s “Life of Samuel Johnson,” errata uncorrected.

Some brag about the worth of their books, but Bernstein values the experience of his: how he acquired some of M.F.K. Fisher’s cookbooks, and visited her Sonoma estate and saw the red claw-foot bathtub he had read about.

Sometimes he wonders how he got here, a life devoted to this store.

Pushing a broom, washing windows as a child, he helped his parents, and years later when his father got sick and died and his mother had a stroke and lingered, Bernstein couldn’t turn his back on their dream.

He had studied anthropology at UCLA, but he gave it up for the armchair. Easier than sleeping on the ground, and the stories were just as rich.

A customer asks if he has anything on Darwin. He will joke that he needs bar codes and GPS to find the titles he’s looking for amid his cluttered inventory, but this request is easy.

At his desk, he pulls out a slipcase edition of “On the Origin of Species.” He opens it, turning to the stark woodcuts that illustrate the text. They were made by Paul Landacre, he says, the story close at hand.

Landacre came to Los Angeles in the 1920s. Once an athlete, he had contracted polio, and with his wife helping him run the press earned a national reputation for his art. Not long after her death in 1963, he died from an explosion in his home from an accumulation of gas, a botched suicide.

“Can you set it aside for me?” the man asks.

Bernstein scribbles the man’s name and phone number on an index card and slides it into his shirt pocket, his filing system.

More than just the stories on their pages, these books capture a writer’s devotion and a community of readers through time.

Sixty-one-year-old Caravan Book Store has one of the most distinguished collections of antiquarian books in the city. Owner Leonard Bernstein is not as concerned about the incursions of the Internet and books going out of fashion as he is about readers becoming less curious, less imaginative.

A young man, composer of music for video games, steps to the counter wanting to buy the score to “Mefistofele” by Arrigo Boito, whose 19th century melodies he hopes to mold to his own.

The passion of collectors is only slightly more obsessive than Bernstein’s. They can run from the Civil War to early aviation history, from cookbooks to the rare and wonderful Zamorano Eighty, the 80 defining books — “Ramona,” “McTeague,” “The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta” — on California’s early history.

But when families talk about breaking up these collections, he advises against it if the books have nostalgic value. Otherwise he will assess their worth with a cool precision.

Sentiment can be hard to let go of. He would never part with his father’s gift to him of Sandburg’s Lincoln, with its custom bookplate, Ex Ex Libris, from one library to another. Or Jack London’s story of San Francisco’s shrimp catchers and oyster pirates in “Tales of the Fish Patrol,” one of his first first-editions.

And he regrets losing his copy of “Treasure Island,” which he read as a boy in the branches of the family rubber tree, high above his frontyard.

::

Night falls, and the glow of the store is cast onto the sidewalk. He feels the seasons change here, rainy days when the streets are splashed with reflections, a spring breeze drawn in from the ocean, December holidays when customers seem more generous, less encumbered.

A young woman steps to the cash register with postcards of Mount Vernon and Monticello. He helps her find the right change. She is a flight attendant on a layover from China, unfamiliar with the currency.

Sometimes he wonders how it will end when he is too old for these old books. He thinks about his grandmother who came to New York from Eastern Europe. She signed her name with an X and saw the world change from airplanes to moon landings.

“We owe it to the future to let the future reflect on what came before it,” he says, wary of sounding philosophical. Groucho Marx is more his style.

He looks at the clock, half past 7, and decides to close. Hitting the lights, setting the alarm, he puts his morning routine in reverse, and the store grows dark again.

Twitter: @tcurwen

MORE GREAT READS:

In Myanmar, a young Rohingya dreams of leaving despite foiled boat journey

Artist Lydia Emily faces down death to spread her light

A night of violence that shattered a South African’s view of her white privilege

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.