Sheriff Lee Baca was consumed by crises

- Share via

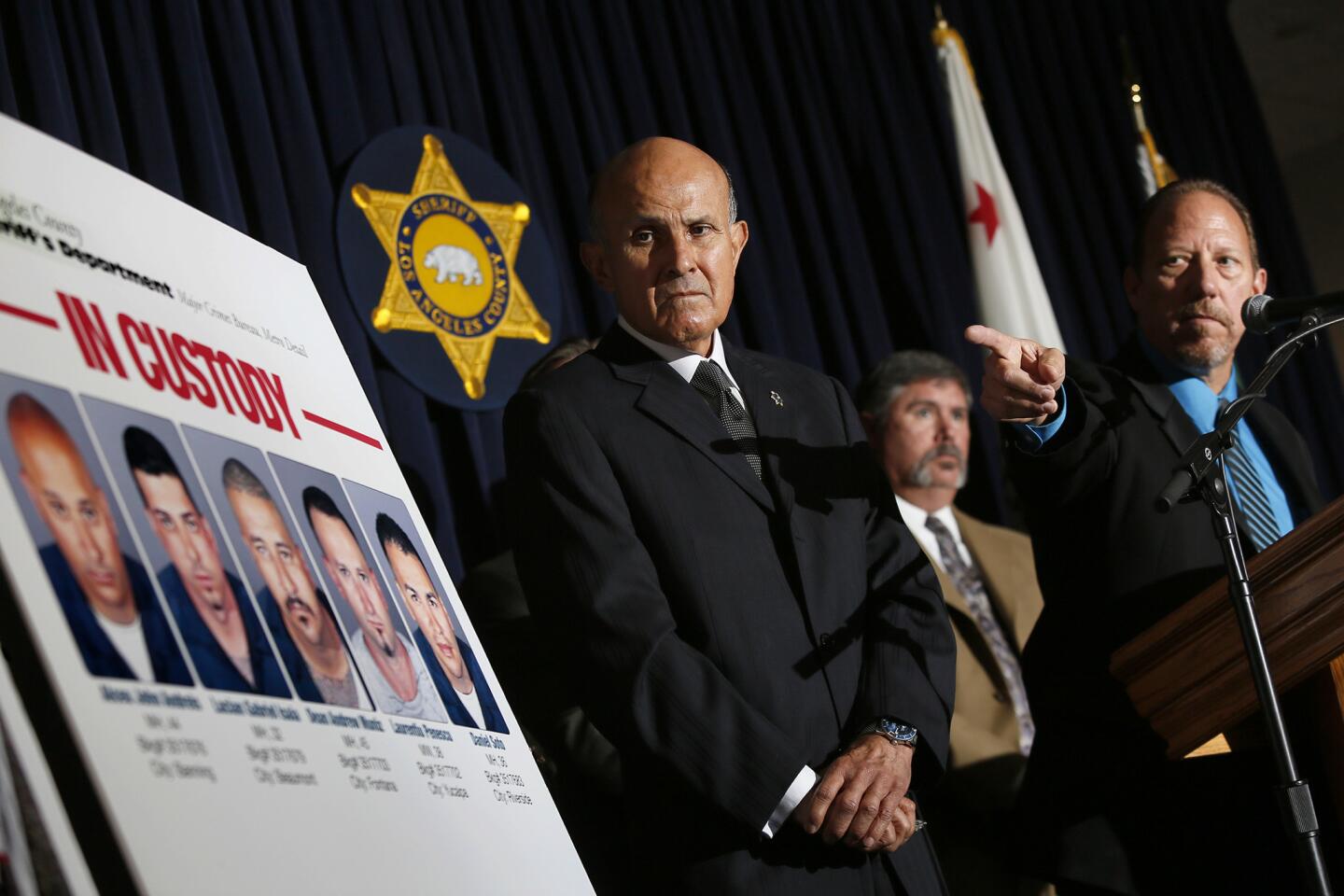

For Sheriff Lee Baca, it was a legacy moment. He was on Capitol Hill, testifying before a congressional hearing on the radicalization of American Muslims. Conservative lawmakers were grilling him, pressing him to acknowledge that the Muslim groups he embraced after 9/11 may have had criminal elements.

Baca wasn’t having it.

“We don’t play around with criminals in my world,” he shot back.

With dozens of cameras trained on him, the sheriff made the case that American Muslims were being unfairly persecuted and should be treated as partners, not suspects, in the fight against terror.

The tense exchange in 2011 made national news, burnishing Baca’s image as a lawman who bucked law enforcement stereotypes and embraced a softer side of policing.

Back in Southern California, a different narrative was playing out in his department.

Just two weeks earlier, Baca’s deputies allegedly beat a man visiting his brother in the Los Angeles County jail in an incident that would later result in federal indictments. Baca’s subordinates had recently hired dozens of officers with histories of serious misconduct. And in the Antelope Valley, Baca’s deputies were involved in searches and detentions that federal authorities would later say violated the constitutional rights of black and Latino residents.

Baca’s defense of Muslim Americans on the national stage would turn out to be a high point in his 15-year tenure. Since then, the Sheriff’s Department has been rocked by one scandal after another. And a different take on Baca emerged: a disengaged manager who lacked the managerial skill and sway to get his 18,000-person department to follow his vision.

As a federal investigation into jail brutality grew, Baca admitted he was out of touch.

“People can say, ‘What the hell kind of leader is that?’ The truth is I should’ve known,” Baca said a few months after his triumphant Washington trip. “So now I do know.”

As Baca makes way for his successor, even his supporters see the contradiction in his legacy. Baca, whose resignation takes effect Thursday, arrived as a different kind of sheriff, one who talked about tolerance, educating jail inmates and policing that wasn’t based on force and intimidation. He leaves a department accused by federal authorities of brutality against jail inmates and racially biased treatment of minority residents.

“I know he’s got to be destroyed inside to be going out this way,” said Brian Moriguchi, head of the union for sheriff’s supervisors.

::

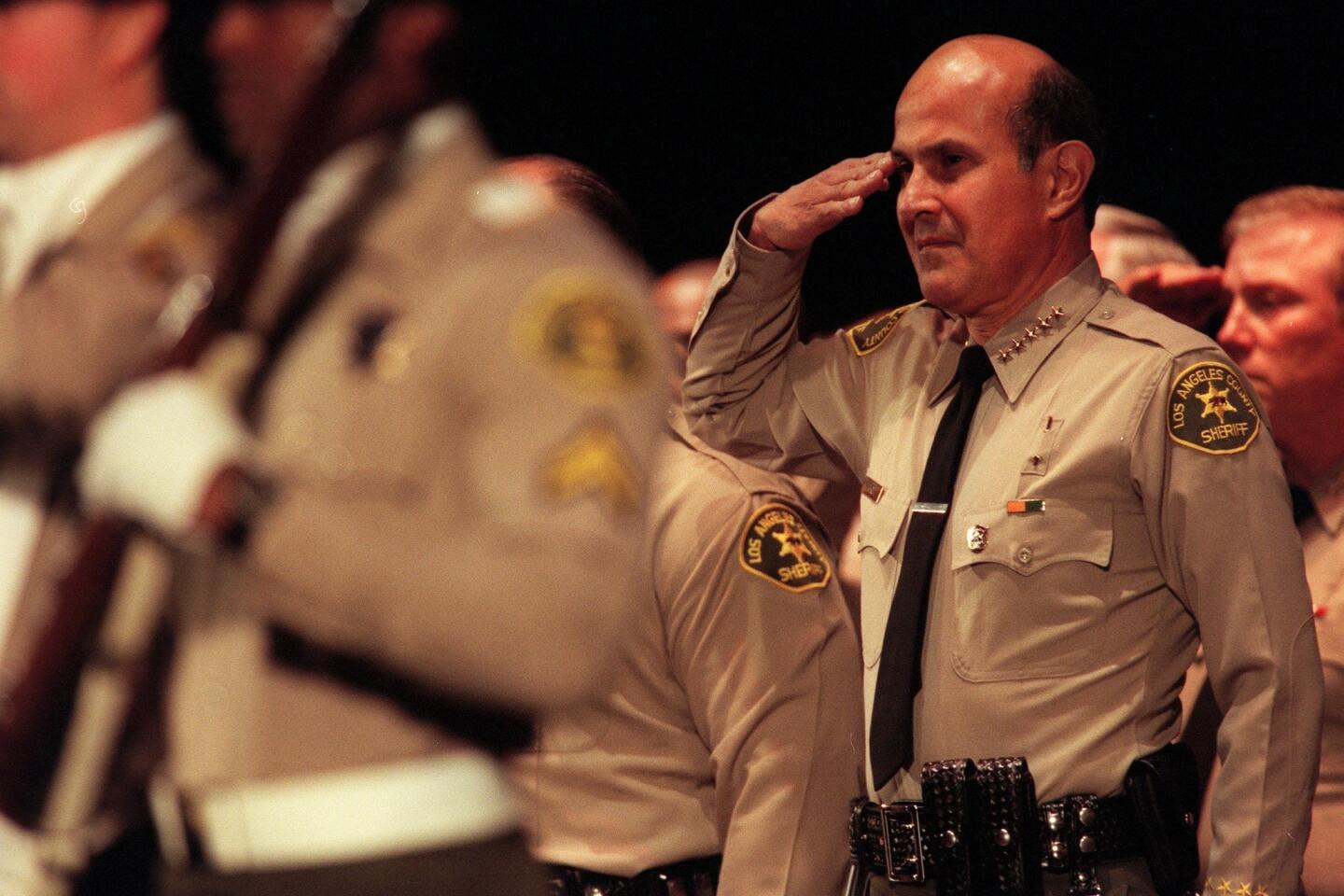

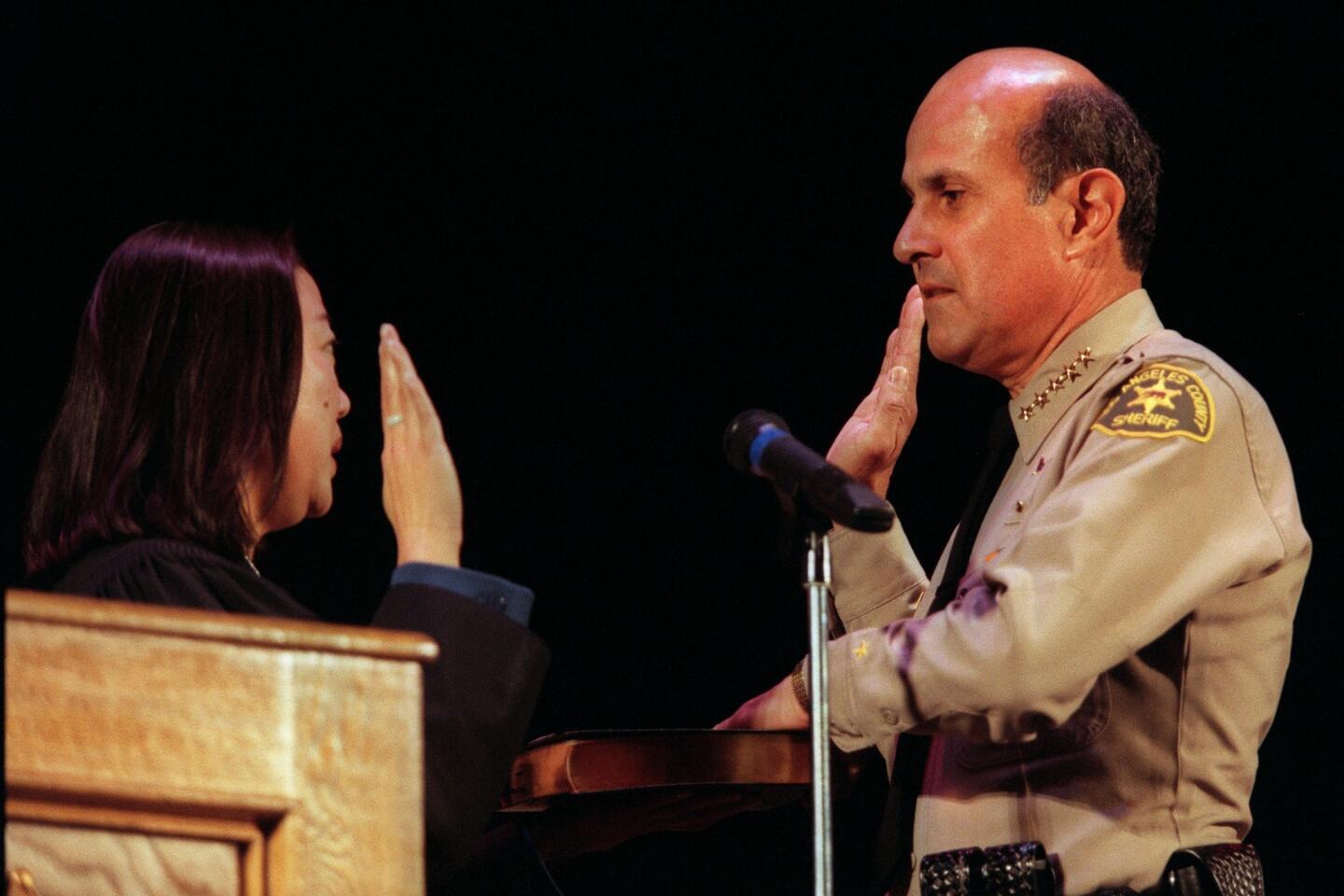

In many ways, Leroy David Baca represented a stark difference from the traditional L.A. law enforcement leader. Raised by his grandparents in working-class East Los Angeles, Baca dropped out of community college. He was hired as a beat cop with the Sheriff’s Department and worked his way up the ranks, earning a doctorate from USC. Along the way, he developed a philosophy about policing that went beyond simply arresting criminals and included rehabilitation and education.

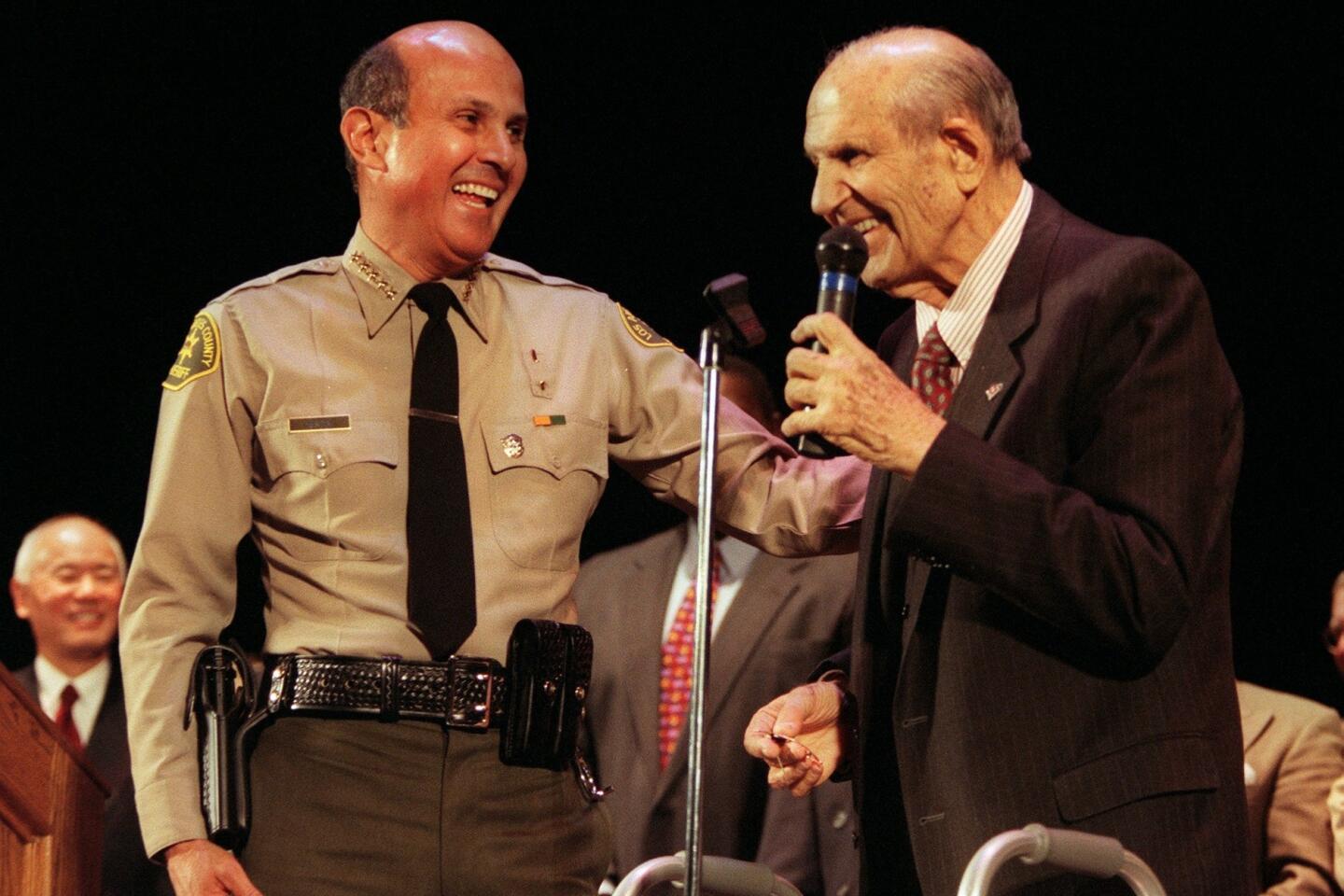

In 1998, as a top commander within the department, he launched a campaign to unseat his longtime mentor, incumbent Sheriff Sherman Block. One top aide recalled Baca’s approach then as being the opposite of Daryl Gates, the controversial former LAPD chief criticized for a militaristic take on law enforcement that alienated minority communities. Baca drew his support from ethnic communities within the county.

“I felt that he was going to be a real change for the department and a breath of fresh air,” said veteran civil rights attorney R. Samuel Paz, who later became a fierce critic of Baca’s leadership.

The runoff between Baca and Block, 74, was expected to be close, but days before the election, the incumbent died from injuries he suffered after slipping in the shower.

In his first years in office, Baca impressed some reformers.

He required his deputies to memorize a pledge to fight against racism, sexism and homophobia. He created dozens of ethnic advisory committees, formalizing a pipeline between his office and the county’s many minority groups. He opened a drug and alcohol treatment center for jail inmates as part of rehabilitation efforts.

Baca successfully pushed for a watchdog agency that would monitor how the department handled allegations of misconduct by deputies. The move was all the more notable because it came at a time when the LAPD was mired in the Rampart corruption scandal.

Baca’s subordinates felt the culture inside the agency shifting, even in subtle ways.

Moriguchi, the union boss, recalled first meeting the sheriff when they shared a flight to a hate crime conference. Moriguchi, a sergeant at the time, had become widely known after he sued the department, alleging he was retaliated against for complaining about an Asian caricature sketched onto a station whiteboard.

“Many department executives held that against me, told me my career was over,” Moriguchi said.

He said he had no intention of bringing the lawsuit up during their flight, but Baca turned to him and brought it up himself, apologizing to the young subordinate for what he had been put through.

“He is an extremely caring and compassionate person,” Moriguchi said. “He’s the kind of guy I’d love to have to my house for a barbecue and talk. But as a sheriff and as a leader that kindness ... is a flaw.”

A few years into his tenure, Baca was faced with a series of problems. Racially motivated violence erupted between black and Latino inmates. Sheriff’s officials were blamed for failing to prevent a string of inmate killings by other inmates.

By the mid-2000s, Baca was under fire for releasing thousands of inmates early from his cash-strapped jails, with many of the freed going on to commit new crimes.

His department was accused of giving actor Mel Gibson preferential treatment following his 2006 drunk driving arrest in Malibu. A year later, Baca’s decision to free Paris Hilton weeks before she finished her jail term for a probation violation made international news.

The sheriff weathered the storms, comfortably winning reelection. The LA Weekly began calling him the “Teflon Sheriff.”

::

In 2011, while walking in New York City after another speaking engagement about the Muslim community, Baca described his approach this way:

“I know I’m a little naive. I know I am overly trusting. That’s who I choose to be. If you’re uncomfortable with others, you’re not in a position to lead. I’ve created somewhat of a palace in my mind because, if you don’t, this world is your prison,” Baca said. “I can take the attacks. Attack me! Am I going to change who I am? No. Because it works.”

But his determination to trust people, particularly his subordinates, set up his downfall, according to more than a dozen county and sheriff’s officials who worked with him.

When Baca’s department came under fire for hiring scores of problem cops, Baca said he had entrusted his former undersheriff to maintain the agency’s recruitment standards. When an inmate abuse scandal broke out, Baca complained of being left in the dark by his top aides. And when it was discovered that sheriff’s officials were fast-tracking friends and relatives for jobs, Baca asserted that the program was started without his knowledge.

County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said Baca made the mistake of trusting subordinates who didn’t fully accept his philosophy.

“You had this disconnect between what he professed and what happened,” he said.

The damage that caused was amplified, those around Baca said, because the sheriff was not particularly interested in the nuts-and-bolts of managing a bureaucracy. Baca’s aides recalled the four-term sheriff devoting his attention instead to pet projects: creating education programs for inmates, reaching out to Muslims both at home and abroad after 9/11, battling homelessness.

That approach at times yielded historic results. Former Dist. Atty. Steve Cooley, for example, credited Baca with spearheading the creation of a state-of-the-art countywide crime lab to help law enforcement solve crimes.

But the approach, according to some aides, also distracted the sheriff and left subordinates grumbling and confused.

In 2010, as the department wrapped up construction of the new South Los Angeles station, Baca inserted himself into minor design elements.

Records and interviews show he wanted the accent tiles in the bathrooms to be green, not red — and the partitions between toilet stalls to be stainless steel, not painted. At an expense of more than $22,000, new products were ripped out and replaced.

A blue-ribbon commission investigating the jails’ problems issued a searing critique of Baca’s management, saying a chief executive in private business who “remained in the dark or ignored problems plaguing one of the company’s primary services for years,” as Baca did, would probably have been replaced.

Despite Baca’s frequent vows to combat racism, the U.S. Justice Department last year accused sheriff’s deputies of engaging in widespread unlawful searches of homes, improper detentions and unreasonable force in what the government said was a systematic effort to discriminate against African Americans who received low-income subsidized housing in the Antelope Valley.

::

Earlier this month, when Baca abruptly announced he was stepping down, he reminded reporters of the good he had done: historically low crime, wide-ranging reforms to his troubled jails, his embrace of the county’s ethnic communities.

“Unfortunately,” said county Supervisor Gloria Molina, “we’re all about the last thing we did.... At the end of the day, he just may be remembered for his resignation, which would be a disservice to him.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.