La Habra quake a reminder about dangerous Puente Hills fault

- Share via

The magnitude 5.1 earthquake that rattled Southern California on Friday was a 10-second reminder of a fault that seismologists believe can produce a catastrophic disaster.

The Puente Hills thrust fault is so dangerous because of its location, running from the suburbs of northern Orange County, through the San Gabriel Valley and under the skyscrapers of downtown Los Angeles before ending in Hollywood.

Experts say a major, magnitude 7.5 earthquake on the fault could do more damage to the heart of Los Angeles than the dreaded Big One on the San Andreas fault, which is on the outskirts of metropolitan Southern California.

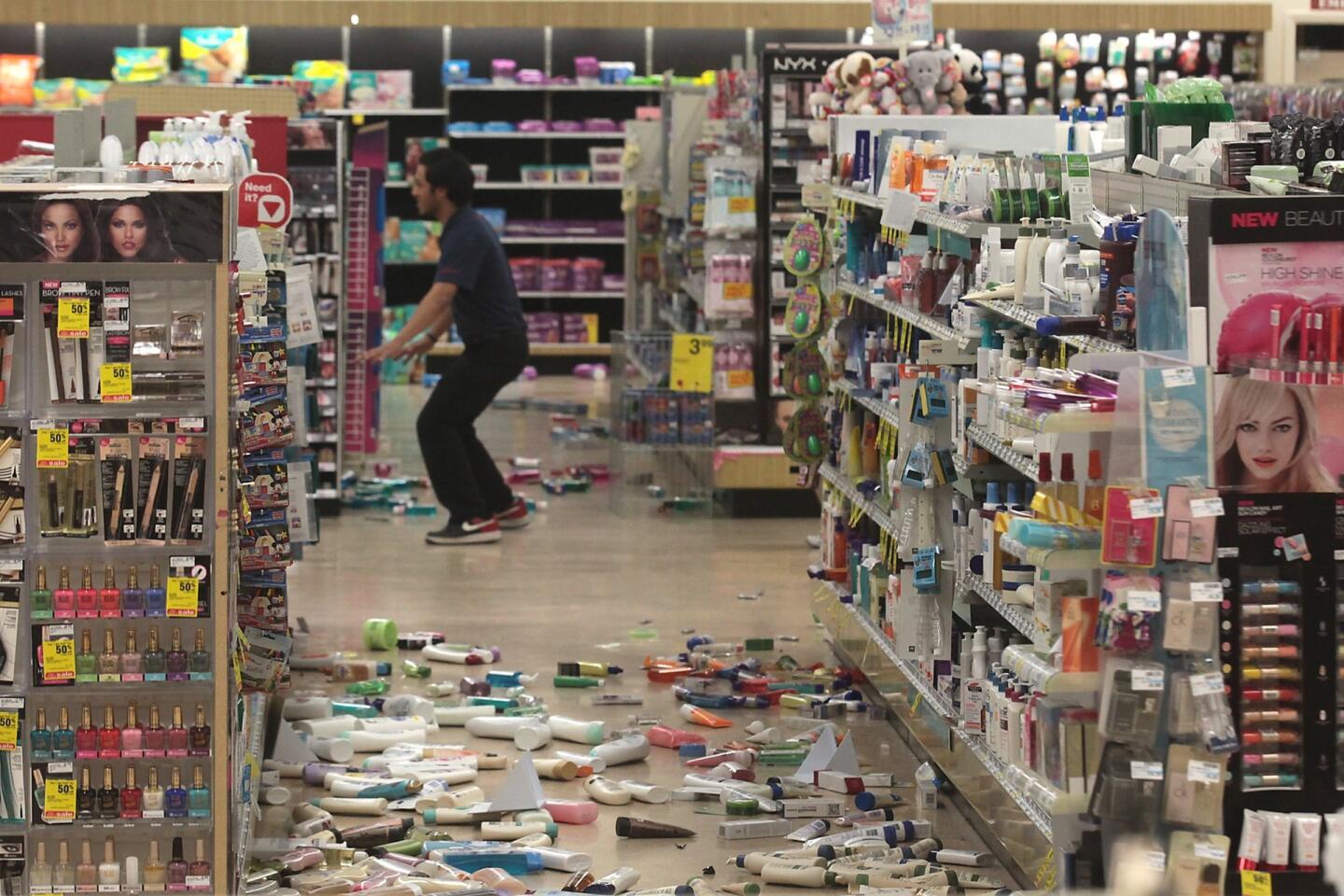

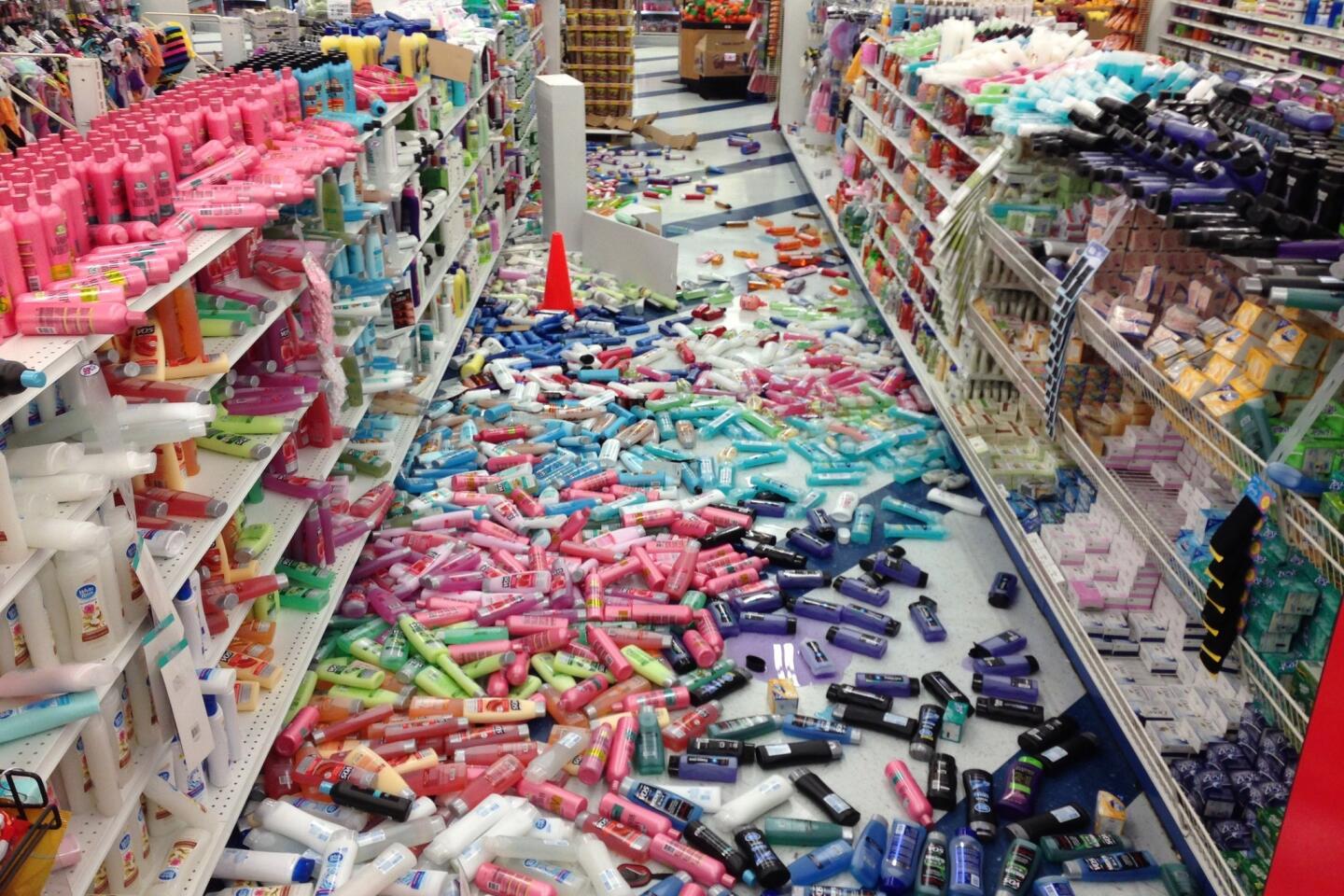

The size of Friday’s quake was considered moderate, but it packed a punch. Residents within 10 miles of the epicenter in La Habra reported toppled furniture, broken glass and fallen pictures. Several water mains broke, and a rock slide in Carbon Canyon caused a car to overturn, leaving those inside with minor injuries.

Officials said more than a dozen homes and apartments were red-tagged because of possible structural damage.

Preliminary checks by the U.S. Geological Survey after the quake show it erupted around the Puente Hills thrust fault system, said Caltech seismologist Egill Hauksson. Further research is underway.

In 1987, another “moderate” quake on that fault killed eight people and caused more than $350 million in damage. The magnitude 5.9 Whittier Narrows quake left old brick buildings in Whittier’s downtown area battered and also damaged some freeway bridges. More than 100 single-family homes and more than 1,000 apartment units were destroyed.

Friday night’s earthquake was caused by the underground fault slipping for half a second, said USGS seismologist Lucy Jones, prompting about 10 seconds of shaking at the surface.

But a 7.5 quake on the Puente Hills fault could cause the fault to slip for an entire 20 seconds — and the shaking could last far longer.

The Puente Hills fault could be especially hazardous over a larger area because of its shape. Other local faults, like the Newport-Inglewood and Hollywood, are a collection of vertical cracks, with the most intense shaking occurring near where the fault reaches the surface. The Puente Hills is a horizontal fault, with intense shaking likely to be felt over a much larger area, roughly 25 by 15 miles.

According to estimates by the USGS and Southern California Earthquake Center, a massive quake on the Puente Hills fault could kill from 3,000 to 18,000 people and cause up to $250 billion in damage. Under this worst-case scenario, people in as many as three-quarters of a million households would be left homeless.

One reason for the dire forecast is that both downtown L.A. and Hollywood are packed with old, vulnerable buildings, including those made of concrete, Jones said.

By contrast, a magnitude 8 “Big One” on the San Andreas fault — more than 30 miles from downtown L.A., on the other side of the San Gabriel Mountains — would cause up to 1,800 deaths, according to estimates.

The shaking from a quake in the center of urban L.A. would be so intense that it could lift heavy objects into the air, Jones said. It has happened before, near the epicenter of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake in the Santa Cruz Mountains. There, the shaking was so bad, “we found an upside-down grand piano.”

“That’s the type of shaking that will hit all of downtown. And everywhere from La Habra to Hollywood,” Jones added.

The violent motion would be amplified by the soft soil underneath the Los Angeles Basin and the valleys, which produces a jello effect as shaking waves wobble off the basin.

Scientists believe the Puente Hills fault has a major quake roughly every 2,500 years but don’t know when the last one was. The San Andreas has quakes more frequently (both the Loma Prieta and 1906 San Francisco quakes were on this fault).

The Puente Hills fault was discovered relatively recently — in 1999. Five years earlier, the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake hit on another “invisible” fault — completely underground — that scientists didn’t know about.

“When Northridge happened,” Jones said, “it was very sobering for us to think we could have that big of an earthquake that doesn’t come to the surface.”

So scientists launched a major study to discover more of these invisible faults. They strung thousands of sensors across the Los Angeles region and set off small explosions underground.

“From that, we saw this Northridge-like structure sitting under downtown L.A., which is horribly sobering,” Jones said.

Video simulations of a rupture on the Puente Hills fault system show how energy from a quake could erupt and be funneled toward L.A.’s densest neighborhoods, with the strongest waves rippling to the west and south across the Los Angeles Basin.

By contrast, the Northridge earthquake, which killed 57, channeled its strongest shaking north to the more sparsely populated Santa Susana Mountains.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.