EPA officers sickened by fumes at South L.A. oil field

- Share via

Federal environmental officers were sickened by toxic vapors as they toured a south Los Angeles urban oil field whose emissions are blamed by neighbors for a variety of ailments, an EPA official said Friday.

Jared Blumenfeld, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regional administrator for the Pacific Southwest, was among those stricken by the fumes during the recent tour of the Allenco Energy Co. site in University Park, about a half-mile north of USC.

“I’ve been to oil and gas production facilities throughout the region, but I’ve never had an experience like that before,” Bumenfeld said. “We suffered sore throats, coughing and severe headaches that lingered for hours.”

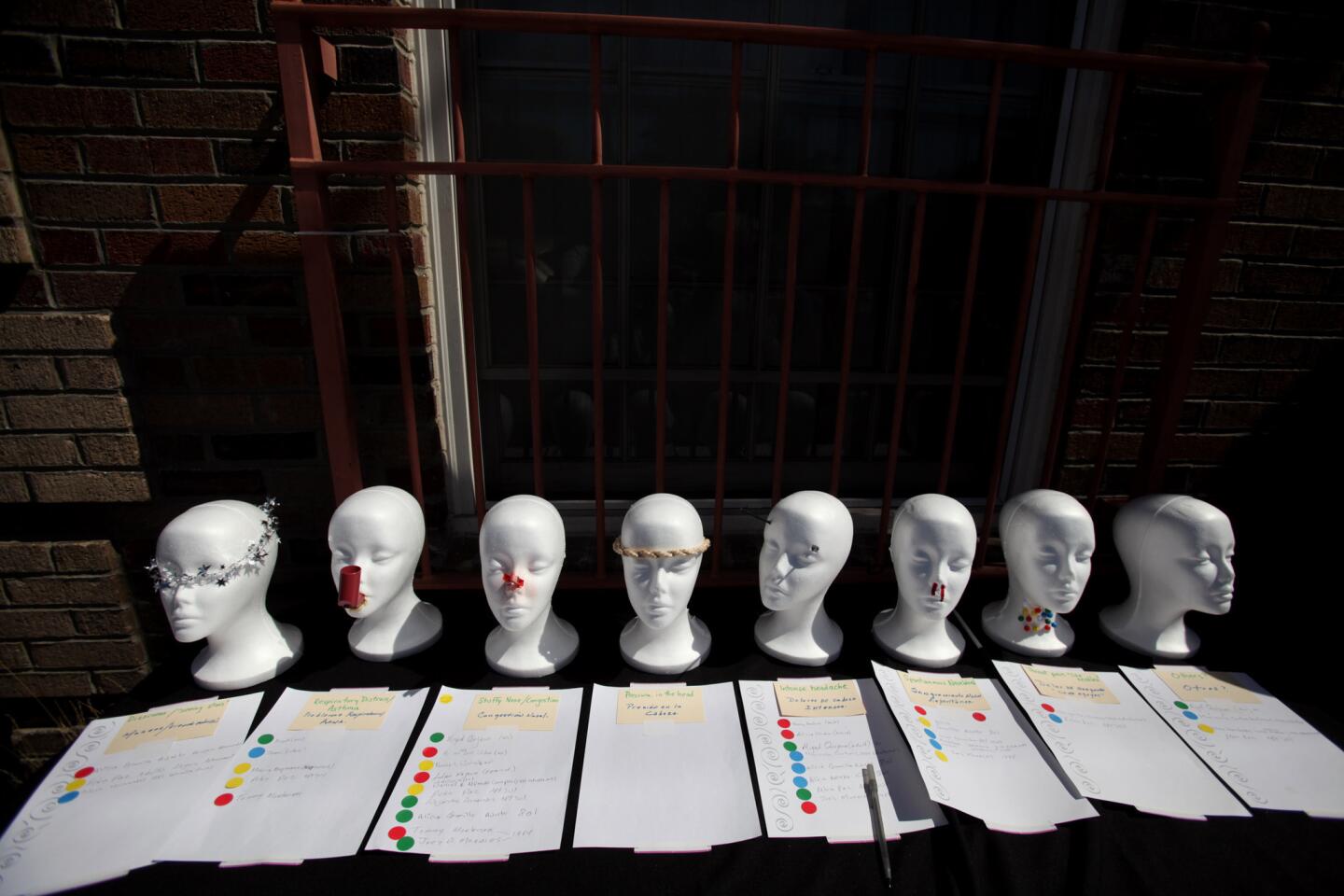

U.S. Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.) on Friday urged Allenco to suspend operations immediately pending completion of an EPA investigation, which was prompted by hundreds of complaints from neighbors who blame the noxious odors for persistent respiratory ailments, headaches, nausea and nosebleeds.

Boxer said EPA investigators who toured the site Oct. 24 “told me that they saw a shoddy operation. They saw oil on the ground. They saw pipes held up by 2-by-4s. This cannot go on.”

The EPA is investigating whether the Allenco operation is in compliance with federal clean air and water laws. The site, owned by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles and leased to Allenco, is surrounded by low-income housing and schools, including the Doheny Campus of Mount St. Mary’s College.

Tensions have been on the rise in the community since 2010, when Allenco boosted production at its wells by more than 400%. Neighbors complained to the South Coast Air Quality Management District 251 times over the next three years. The agency responded by issuing 15 citations against Allenco for foul odors and equipment problems.

However, frustrations over the air district’s inability to say whether fumes from the oil field are hazardous has triggered the EPA investigation and others by the Los Angeles County Department of Health, the Los Angeles city attorney’s office and the archdiocese.

Investigators hope to determine the cause of the ailments and scrutinize the validity of Allenco’s operating permits, as well as the archdiocese’s lease agreements with the company.

“This is an exceptionally important moment for this community,” said Nancy H. Ibrahim, executive director at Esperanza Community Housing Corp., a nonprofit affordable housing developer in the area. “The AQMD has been complicit in what has become a community health emergency by apparently requiring a mass body count before we get their full attention — and an appropriate response.”

Boxer, who said she learned of the University Park illnesses from the Los Angeles Times, said she called upon the archdiocese to act.

“The Catholic Church is a strong advocate for children,” Boxer said. “Well, if you love children, you don’t expose children to dangerous things.”

Allenco was unavailable for comment. Monica Valencia, an archdiocese spokeswoman, said, “We take the residents’ concerns seriously. We are examining our lease with Allenco to ensure their operations are in compliance with our agreement. We continue to work with all involved parties to see that health standards are being met at the site.”

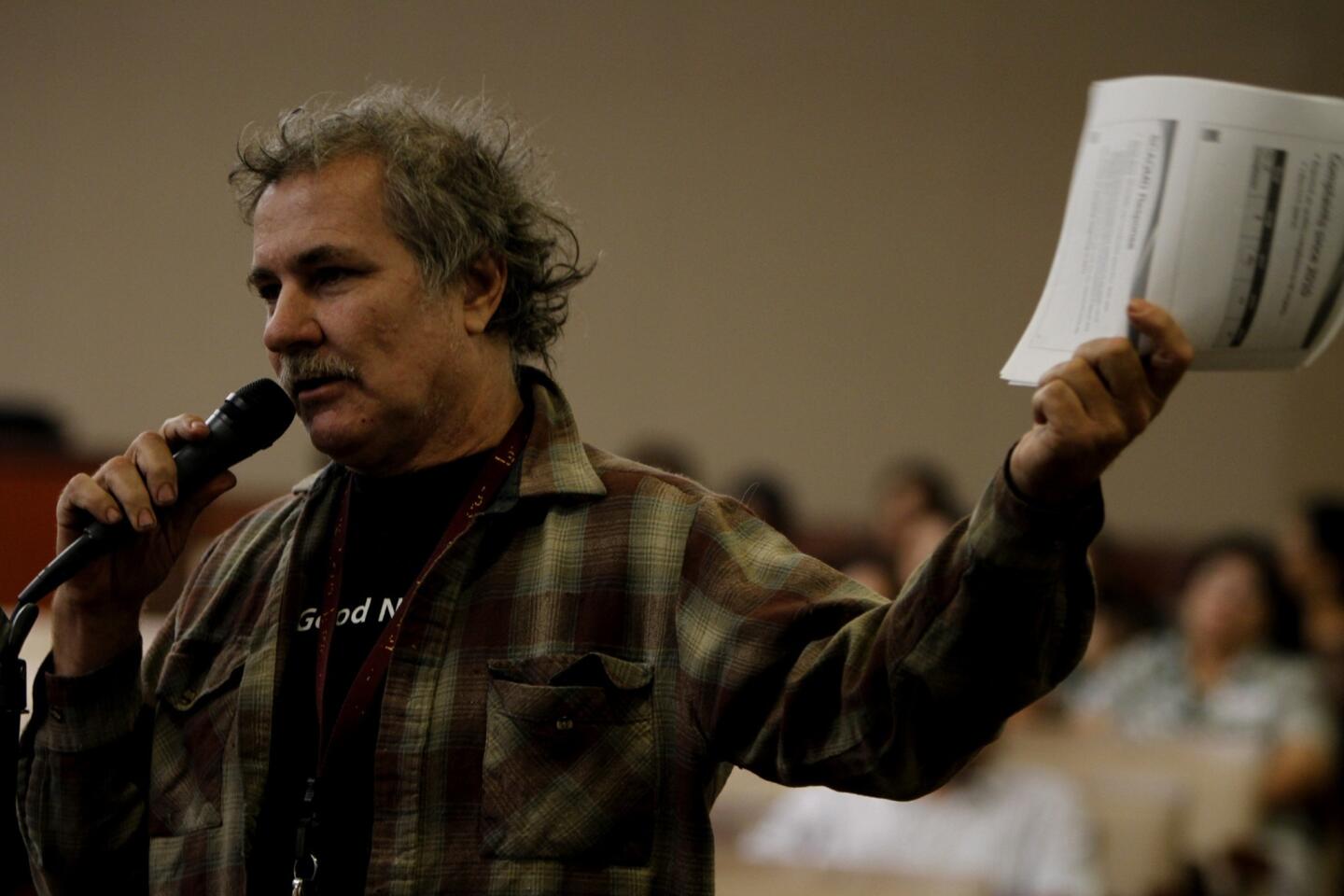

After analyzing three air samples collected in 2011, the district concluded that the odors posed no health risks. Two weeks ago, Barry Wallerstein, the agency’s executive director, tried to assure a crowd at a town hall meeting that recent air samples taken at Allenco also showed that the air was safe to breathe.

A new round of air samples, however, has detected “brief episodes of elevated hydrocarbon levels around the facility,” air district spokesman Sam Atwood said. “We will continue to conduct air monitoring until we can figure out what’s causing them.”

The facility has a history of violations. For example, an air sample taken from a wastewater tank discharge line Aug. 29, 2011, detected levels of hydrocarbons from volatile petroleum products that were 10,000 times higher than ambient levels, air quality district lab reports show. Although some hydrocarbons are toxic, the analyses did not identify the hydrocarbons in the samples or determine how long they had been leaking.

EPA and county health investigators suspect that constant exposure to extremely low levels of pollutants, including hydrogen sulfide, a colorless flammable gas that occurs naturally in petroleum and natural gas, is contributing to the illnesses reported by neighbors.

Angelo Bellomo, director of environmental health for the county health department, said the symptoms described by neighbors “are not inconsistent with what we would expect to see after exposure to low levels of hydrocarbons. So, while the detectable concentrations of hazardous pollution may be below regulatory standards, they are nonetheless making people sick.”

He said his agency will work to develop an alternative set of standards to cover conditions like those in University Park.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.