Do childhood rapes by her father excuse her crimes?

Tatiana Thibes had a horrific childhood. Now prosecutors ponder how to factor that in to the punishment for her role in a burglary.

- Share via

After her father was sentenced to life in prison, Thibes spoke of overcoming her 19-year ordeal by becoming a therapist to help other victims of sex abuse.

But four years later, the 33-year-old recently appeared in the same downtown Los Angeles courthouse where she once testified against her father, this time as a defendant.

Thibes has been in court for multiple hearings while judges and prosecutors decide what punishment she deserves. She could be sentenced to prison after her conviction last year for helping three gang members burglarize homes in Tujunga. (The Times generally withholds the name of sex crime victims, but Thibes wanted her name used.)

"I know I messed up. I feel like I let a lot of people down. I'm ashamed," Thibes said in a recent phone interview from jail.

Cases like Thibes' are a thorny challenge for the criminal justice system, one that judges and prosecutors routinely wrestle with: How should the courts punish serious offenders who have themselves endured difficult or abusive upbringings? The prosecutor who tried her burglary case said he feels torn as his office considers an appropriate sentence.

Rick Carr, a veteran Torrance police sex crimes investigator, was used to hearing harrowing accounts of abuse, but even he was shocked by the report he took in 2005.

Thibes was living in a Torrance apartment when she spoke to Carr about the sexual abuse. By then her father, Lindolfo, had already been arrested for stabbing her in Las Vegas.

She told Carr that her father began assaulting her when the family was living in Los Angeles and her mother was working as an overnight baby-sitter. He plied her with alcohol and drugs, starting with marijuana and later cocaine. He threatened to kill or blind her if she reported him.

He pulled her out of school when she was in sixth grade and rigged the family's West Adams home with surveillance cameras to monitor her movements and prevent her escape. He tortured her by beating the soles of her feet with a wooden stick and covered her head with a plastic bag until she passed out.

At 17, she gave birth to a child by him. By 24, she had had two more of his children.

"What this woman had to endure was unspeakable," said Carr, now retired from the Police Department.

Los Angeles County prosecutors filed sexual abuse charges.

At a trial in 2009, Carr recalled, Thibes' father acted as his own attorney and leered at his daughter during her testimony. He accused her of lying, but jurors convicted him of more than a dozen counts of rape and other types of sexual assault. He was sentenced to 109 years to life in prison. He had also been sentenced to prison in Nevada in the stabbing case.

During the L.A. case, Carr said, it seemed like Thibes was handling her life well. She and her children had moved into a house in Victorville with a boyfriend, and the couple had a son together. Her children enjoyed showing off their homework and school reports to visitors.

In an interview with The Times, Thibes recalled taking her oldest daughter to school on her first day of sixth grade. She was determined, she said, to give her kids the type of normal childhood she never had. But the experience of raising her children also reinforced the horrors of her own upbringing. She began pulling away from her children, she said.

"I was acting like a wild teenager rather than the adult that I am," Thibes said.

She started therapy after her father's arrest, but talking about her abuse made her feel worse, she said. So she quit.

"Not talking about it was the only way to protect my sanity," she said. "I didn't want to face my worst fears, and that was getting counseling and confronting my abuse."

Although some sexual abuse victims are more resilient, others suffer long-term psychological damage, mental health experts say. Some victims experience extreme anxiety, a sense of guilt and other problems. Some, as in Thibes' case, turn to drugs or alcohol, increasing their likelihood of ending up behind bars.

“What this woman had to endure was unspeakable.”

— Rick Carr, police investigator

Eighteen months after her father's arrest, Thibes crashed while driving drunk on the 105 Freeway. Two of her passengers were briefly hospitalized. She was placed on probation.

She broke up with her boyfriend and after her father's trial started dating Adam Ortiz, a gang member with a long criminal record. Months later, Ortiz was sent to prison for being a felon in possession of a firearm.

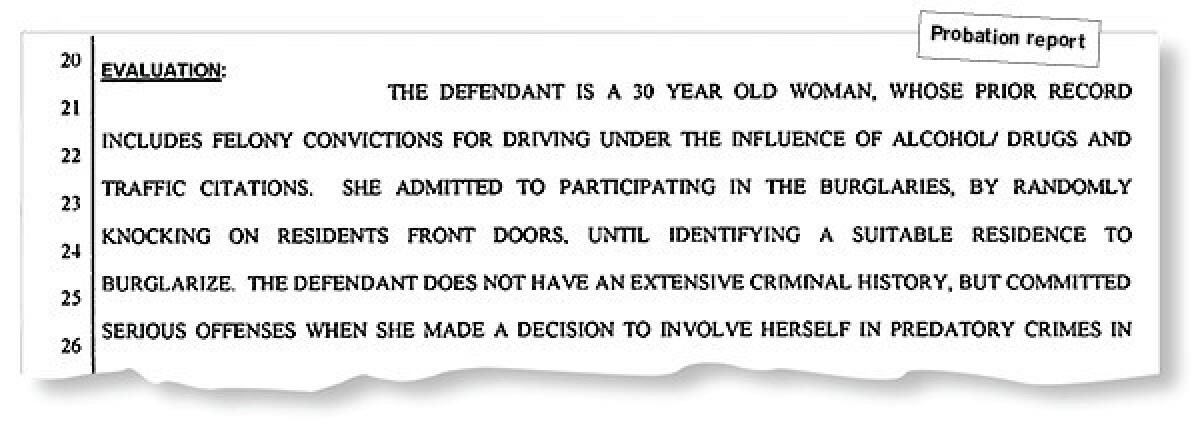

On June 1, 2010, three months after Ortiz's release from prison, Thibes went knocking on doors in a Tujunga neighborhood. "I'm here for an appointment with Sue. Is Sue here?" she asked one resident who came to the door, according to court records.

After finding homes where no one answered, Thibes returned to her minivan parked nearby. Ortiz, 25, and two other gang members got out and ransacked a house.

Police officers, tipped by a neighbor's call, responded and saw Thibes speed off with the men in the minivan. She ran stop signs and crashed while trying to escape.

A jury last year convicted her and the three men of residential burglary and attempted residential burglary and concluded that the crimes were to benefit a street gang. The men were sentenced to prison terms of at least 12 years.

Thibes has expressed remorse. She said she has never been a gang member and described Ortiz — the father of her youngest child — as violent and controlling. She feared saying no to him.

"All I pretty much know is chaos," she said.

After Thibes was jailed, a dependency court removed her children from her care. Thibes' attorney, Ron Seabold, said sending her to serve her sentence at a rehabilitation center where mothers can live with their children could help convince a dependency court judge that Thibes should be reunited with her five children, who range in age from 2 to 16.

Deputy Dist. Atty. Richard Gallegly, who prosecuted Thibes, said that by scoping out targets for burglary, Thibes acted as "the face of this crime." She was 30 and took an active role in a sophisticated plan to victimize others, he said.

But the horrifying nature of Thibes' history stands out, Gallegly said. He compared her to victims of recent high-profile sexual abuse cases, including Jaycee Dugard, who at 11 was kidnapped in South Lake Tahoe and repeatedly raped during 18 years in captivity.

"She wasn't far off that," Gallegly said. "We want to give her a chance, but she's in her early 30s.... When will she stand up and take responsibility?"

Gallegly said his office is willing to consider allowing Thibes to serve out her sentence in a rehabilitation facility if she is legally eligible.

Among the hurdles, however, is a state law that says someone who commits a serious crime, such as burglary, while on probation for another felony must be sentenced to prison. Thibes had one more week on felony probation for her 2006 drunk driving offense when she was arrested for the burglaries, court records say.

Immigration authorities had flagged her case for possible deportation, preventing her release from jail. Thibes' parents had brought her to the United States illegally from Brazil when she was 6. In July, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services sent Thibes a letter denying her request for permanent residency, citing her burglary conviction.

“I want him to die miserably in jail.”

— Tatiana Thibes, speaking of father who raped her

Public Counsel, a nonprofit public interest law firm, appealed the decision, arguing that Thibes had no choice in her parents' decision to bring her to this country and that she feared her father's family in Brazil might retaliate against her for testifying against him if she is deported.

On Wednesday, immigration authorities notified Public Counsel that the appeal had been granted and Thibes would become a permanent resident. Her public interest attorney, Gina Amato Lough, said she was hopeful that the decision would remove a key obstacle to her entering a reentry program for mothers.

It is uncertain when Thibes will be sentenced. She works in the booking area of the women's jail in Lynwood, helping deputies admit inmates.

She said she regularly talks by phone to her children. Recently, she has been trying to soothe her 5-year-old son's anxiety about starting kindergarten. The children, she said, always ask when she is coming home. She has stopped telling them it will be soon.

Thibes said she wants her father to suffer behind bars rather than follow the example of Ariel Castro, who killed himself in prison last month after being convicted of repeatedly raping three women he'd imprisoned in his Cleveland house for more than a decade.

"I want him to die miserably in jail. I don't want him to die and end his life that quick," she said.

Spending time in L.A. County jail, Thibes said, has given her time to reflect on what has happened to her and made her realize that she needs therapy. She said many of the women in jail share tales of their own abuse with her. She hopes to obtain her high school diploma and one day write a book about her life. She still wants to become a therapist.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.