Pasadena repurposes parking meters to collect change for homeless

- Share via

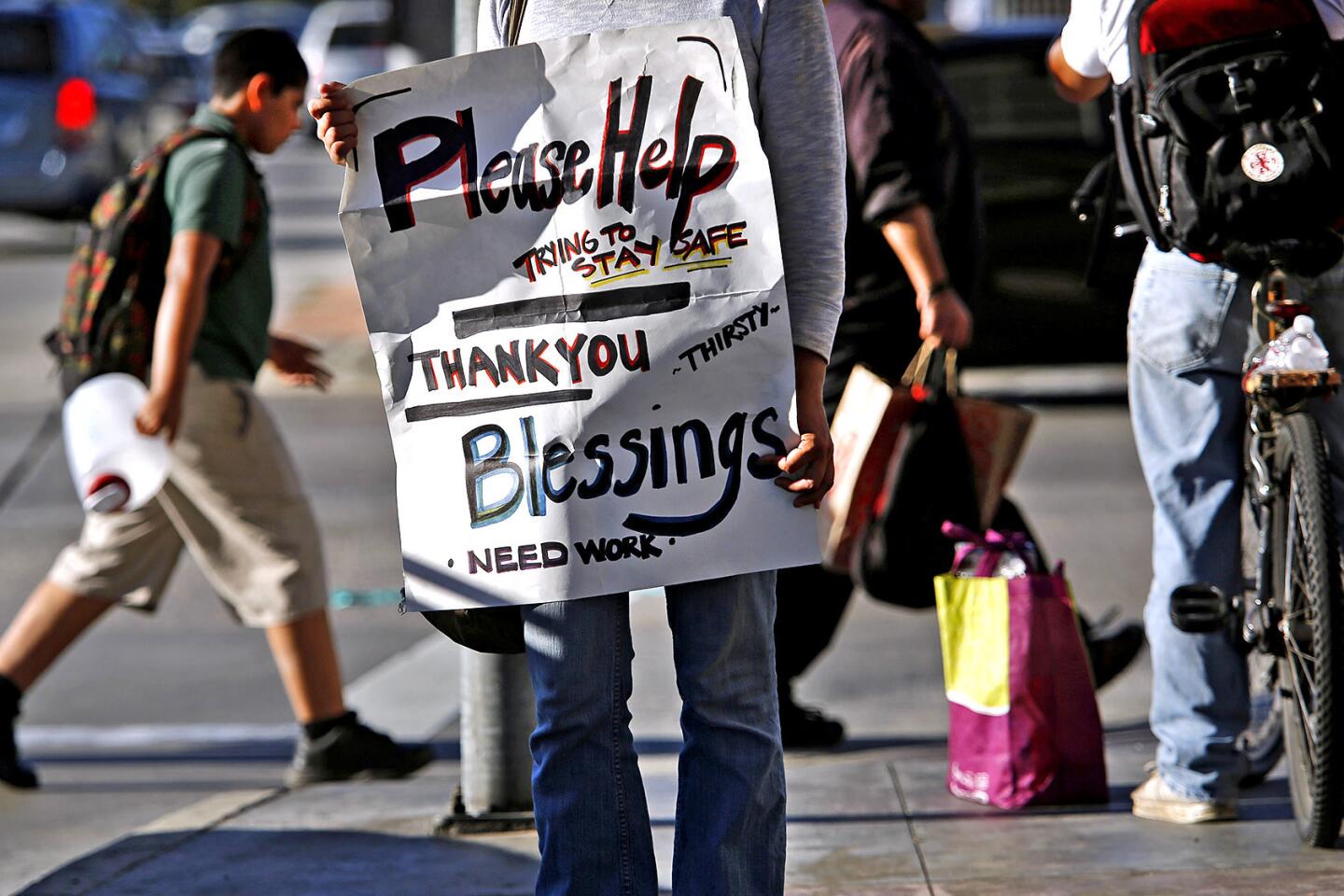

It’s a quandary faced by anyone who’s been asked for money by a homeless person: Will my spare change stave off hunger or support an addiction?

Pasadena is now testing an alternative to giving to the panhandler.

Fourteen repurposed parking meters across the city will collect change for nonprofits that serve the homeless. The meters, painted bright orange and decorated with smiley faces and inspirational sayings, are supposed to raise awareness for the city’s homeless programs.

Pasadena is the first city in Los Angeles County to try the donation meters, though Los Angeles has been talking about trying them out in downtown. Officials don’t expect to raise huge sums of money: The two meters currently in place have raised just $270 over three weeks.

“This is a clear alternative where people contributing know that all the money will go to effective services,” said Pasadena Housing Director Bill Huang.

But the meters are rooted in a more controversial idea — that putting money directly into the hands of homeless people is not an effective way to help them.

Some homeless advocates say the donation meters lack the human element normally found in charitable giving and monopolize money that might have gone to genuinely needy people.

“If we would get serious about addressing the actual economic and social issues that we find so offputting, we wouldn’t need meters,” said Paul Boden, director of the Western Regional Advocacy Project, a homelessness advocacy group.

He called the meter programs “asinine” and says they are designed to help cities push out the homeless. In San Diego and Denver, for example, the donation meters were used as panhandling deterrents, installed in areas where homeless people gathered to ask for money. Pasadena officials said their main goal is to raise awareness — but the meters could reduce panhandling somewhat.

The view on the streets of Pasadena is mixed.

Dorothy Edwards, 56, used to panhandle by the Target in eastern Pasadena. She’d use the money to buy food for her dog, rain gear and tents. Buying her own supplies helped her feel independent, but the money also made it easier for her to stay homeless, she said.

“Homeless people wouldn’t be out there doing that if they didn’t really need it,” said Edwards, who found permanent housing in 2011 after a caseworker approached her. “But when you look at the big picture, the meters are going to be a long-term solution.”

But other homeless people are wary of the idea. Holly Johnson, a woman panhandling on Lake Avenue, said that nonprofits don’t always spend money on what homeless people need. Granola bars are pointless for people without healthy teeth, as is canned food without a can opener.

She needs money for her own reasons — underneath an eyepatch, her eye is red and swollen from infection. Women living outdoors are especially vulnerable, she said, and panhandling money could pay for a hotel room where she could sleep without fear of sexual assault.

“It’s a nice idea,” Johnson said. “But we won’t get that money.”

Pasadena leaders argue the meters could stimulate giving by offering donors some assurance that their money won’t be used for drugs or alcohol, he said.

Huang cited a recent survey by a business improvement district in San Francisco in which 44 percent of panhandlers surveyed admitted to purchasing drugs and alcohol with handouts, in addition to food. About 31 percent of visitors to San Francisco’s Union Square said they would prefer to donate to social services supporting the homeless, rather than give money directly to the panhandlers. More than half of visitors to Union Square were afraid that panhandlers would not spend the donated money wisely, the survey found.

Since 2007, Denver has installed 55 repurposed parking meters to collect donations. Officials claim the meters have cut down on panhandling while raising more than $30,000 annually for food, housing and therapy for the homeless.

In other cities the results have been more modest. In Orlando, 15 parking meters raised just $2,027 in three years — just $27 more than what the city spent to install them. In downtown San Diego, about 20 meters generate about $3,600 a year in change, though officials with the downtown business improvement district say the meters have helped them raise $50,000 more through grants and sponsorships.

The Pasadena meter campaign was designed by a class of students at the Art Center College of Design at a cost of about $350,000, including marketing, design and class materials, paid for by grants from East West Bank and other corporate sponsorships. The meters were donated by IPS Group, and most of the funds were spent on the design of the campaign, Huang said. No city funds were used.

The United Way of Los Angeles and the Flintridge Center will collect the meter donations, and local nonprofits targeting homelessness can apply for funding. Businesses can also sponsor meters for a $1,500 annual donation.

Huang says the money could help low-wage workers pay their back rent to avoid eviction, build housing for the most chronically homeless, and help fund the development of affordable housing. Programs like these have helped cut Pasadena’s homeless population in half over the last three years, down from 1,300 in 2011 to about 650, officials said.

On a recent day in Pasadena’s Central Park, Fernando Ruiz and Michael Castillo relaxed at a picnic table as they waited for the weekly feeding program in the park.

Ruiz, homeless for eight years, was cautiously optimistic about the meters. He recycles when he needs cash and never panhandles — the people who do, he says, are the desperate ones who want to purchase drugs and alcohol.

“I hope they put a lot of them around. Put a meter on every street. I do hope it works,” Ruiz said.

[email protected]

Twitter: @frankshyong

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.