Linked Charities Bank on the Chavez Name

- Share via

KEENE, Calif. — Paul Chavez lives a stone’s throw from the two-bedroom home where he grew up and his mother still resides. His commute is a short walk across a bucolic compound here in the Tehachapi Mountains to the nondescript building where he oversees charities founded by his father, Cesar Chavez.

Down the hall, Paul’s brother-in-law, Arturo Rodriguez, runs the United Farm Workers union and several related charities. Rodriguez also lives on the sprawling grounds, as does Paul’s younger brother, Anthony, who runs radio stations owned by a UFW affiliate.

Paul’s sister Liz works here too. She learned accounting as a teenage volunteer and went to work after high school for the movement her father ran. Today she is comptroller for the UFW and also handles the finances of several charities.

FOR THE RECORD:

UFW —A series last month on the United Farm Workers contained three factual errors about the history of the labor union and its related organizations. Health clinics operated during the 1970s were run by the UFW-affiliated nonprofit National Farm Workers Health Group, not the union directly, as reported Jan. 8. UFW officials said that a Fresno developer who partnered with Cesar Chavez to build for-profit housing donated his services and did not split the profits from the developments, as reported Jan. 9. And UFW officials said a school bus abandoned in a back field at union headquarters was not one of the buses used to transport boycott volunteers across the country in the 1970s, as stated in the Jan. 9 article, but was left by a peace activist who never returned to claim it. In addition, the Jan. 8 article reported that the UFW “board deleted all specific references in the UFW constitution to agricultural workers, including the preamble.” To clarify: The board deleted the entire preamble and amended the constitution to include all categories of workers, so that the UFW constitution no longer applied only to agricultural workers and related laborers.

From their remote perch amid rolling hills and gnarled oaks 30 miles east of Bakersfield, Cesar Chavez’s heirs run a thriving family business that has prospered even as the labor union has floundered. They have capitalized on the Chavez name and developed a complex financial web that helps enrich the organizations they oversee.

In dollars, energy and passion, the charities are the heart of the network known as the Farm Worker Movement. Between them, Rodriguez and Paul Chavez head more than a dozen tax-exempt groups that bring in $20 million to $30 million a year. Their primary business is to build and manage affordable housing projects, run Spanish-language radio stations and invest in projects that burnish the image of Cesar Chavez.

A charity does not pay taxes because it serves a public good. Charities are legally required to get the best value for the people they serve.

Instead, the Farm Worker Movement operates more like a family business, making financial decisions in order to expand the enterprise and enhance the founder’s reputation.

The entities enrich one another, buying services from each other that are not necessarily the best available deal. The various organizations reported paying more than $1 million to the UFW-sponsored health plan in 2004, for example — insuring hundreds of employees in a fund that was designed to help farmworkers but now has only a few thousand participants because the UFW membership has dwindled.

The UFW and its related charities do business with friends. Records show they have sold real estate at below-market rates without seeking independent appraisals or opening up the bidding process; in one case, insiders resold a parcel for a $1.1-million profit.

The charities prop up the labor union, which struggles for members. The affiliated organizations buy services such as accounting and human resources — yielding more than $500,000 in income for the UFW in 2004 — although several state reviews have criticized financial management provided by the union.

The Farm Worker Movement’s financial strategy flows from a mission statement adopted a few years ago: Change the world by achieving economic and social justice and help 10 million Latinos by the year 2015.

“Before the vision statement, I was going crazy. I was thinking, ‘I’m not doing my part,’ ” said Paul Chavez, who worried because his charitable efforts were not aimed primarily at farmworkers. “Now I can go to bed at night knowing that while I feel for the union and I want them to grow and all that, I understand that my contribution has to be made on the service side.”

The bulk of the movement’s income is on the side of the ledger that Chavez oversees. He runs the National Farm Workers Service Center, which collects rents on the apartments it owns and operates, along with fees for housing development and management, and revenue from radio ads and sponsorships.

In 2003, for example, the Service Center earned $10.8 million from managing property and $6.8 million from the radio stations and spent roughly the same amount operating those enterprises, according to financial statements. In 2004, the Service Center reported spending $1.1 million on management costs and $9.87 million on programs, primarily the housing projects and radio stations. After payroll, the largest expenses are rent, travel and interest on loans.

Chavez also heads the Cesar E. Chavez Development Fund, which sits on almost $10 million and uses the interest to help support the Service Center and other related charities — even as the UFW issues desperate pleas for the donations that make up one-third of the union’s $7-million budget.

The business of organizing farmworkers has become almost an afterthought, like the junked cars and abandoned school bus that once transported boycott volunteers and now litter a back field on the UFW’s 180-acre campus.

“At times people might wonder and question the resources that go into other things,” said Mark Splain, an AFL-CIO official who was on loan to the UFW in 2004 to set up a training program for the union’s organizers. “I’d be slow to jump to the broad-based critique that these things don’t matter or don’t fit. This is a movement.”

The movement’s founder has been dead for more than a decade, but Cesar Chavez is key to how the organizations raise and spend money today.

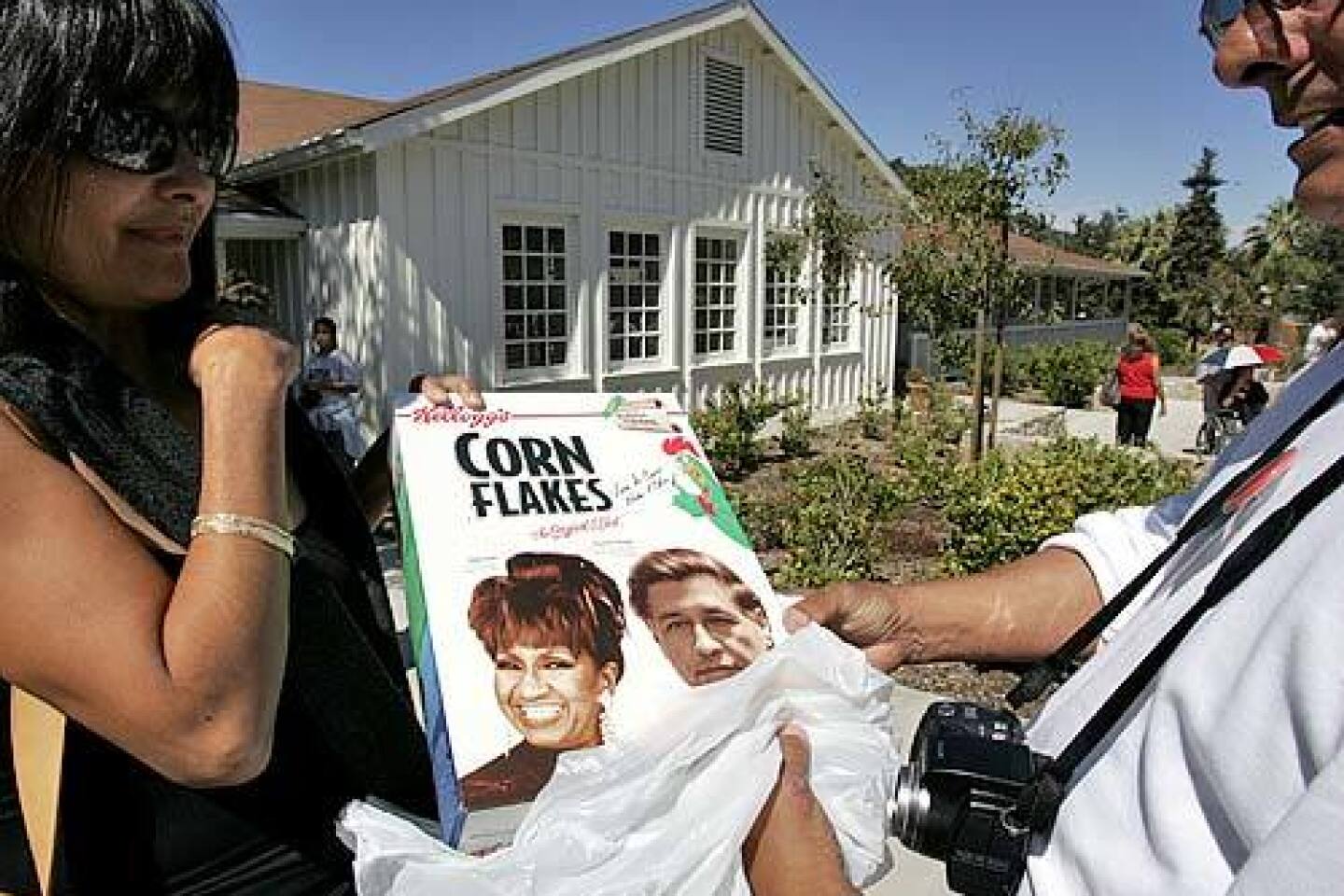

Invoking his name and legacy has helped attract public money (more than $10 million in state grants in recent years), private support (more than $3 million from one philanthropic organization, the California Endowment, in the last few years) and individual donations ($2 million a year to the union alone). Last fall, the Kellogg Co. donated $25,000 to the Cesar E. Chavez Foundation and featured his likeness on a cornflakes box for Hispanic heritage month.

“A lot of times we’re invited to places just because of the UFW,” Paul Chavez said, readily acknowledging he takes advantage of the name to help the Service Center. “It opens the door. But then you have to be able to sell yourself on the basis of the work you do . People like the association with my dad.”

Public records paint only broad outlines of how the UFW and its related charities take in and spend their money. The leaders are able to avoid scrutiny by not indicating the affiliations and transactions between related groups on federal tax returns and inaccurately reporting that they receive no government funding.

A rough picture drawn from tax returns shows that about half the organizations’ spending goes to pay employees — more than $12 million in 2004, the last year for which records are available.

About half of that is spent on employees who develop and staff the housing projects and the nine radio stations, including the latest and most successful, a hip-hop station in Bakersfield. Started by Cesar Chavez to communicate with farmworkers, the network known as Radio Campesina has evolved into a commercial success by adopting a format of mostly popular music and catering to a younger audience and advertisers eager to reach the growing Latino market.

“We want to be able to reach the younger generation, because, man, people are growing up not knowing Cesar Chavez, not knowing the Farm Worker Movement,” Rodriguez said.

The Cesar E. Chavez Foundation aims to correct that as well, focusing on educational initiatives and the construction of a memorial, visitor center and retreat facility at the UFW headquarters. The foundation reported $3.7 million in assets on its most recent tax filing; the organization spent $1.1 million, the majority on staff. Of the total, the organization reported $842,760 went to program expenses, from fulfilling speaking engagements to teaching youths the principles of Cesar Chavez.

The other principal charities, headed by Rodriguez, have annual budgets of less than $2 million each and also spend about half on salary, with the remainder going to administrative expenses and consultants.

Though top officials in the various groups earn more than $100,000, the compensation is modest compared with that of comparable organizations. The movement’s payrolls include about a dozen Chavez relatives.

Recently, Paul Chavez has hired more outside professionals, including a chief financial officer from a Silicon Valley company. But the family still plays a central role.

“I think that what people have got to remember is that this is all we’ve ever done, right?” Chavez said. “It’s been a big part of who we are. The fact that we’re sticking with it to me isn’t anything unusual.”

The following three cases, all involving state funds, illustrate in detail how the leaders of the Farm Worker Movement leverage support from one another, exploit Cesar Chavez’s name and legacy, and spend money enriching their own enterprise.

LUPE: Political Clout Helps the Entire Movement

In the spring of 2003, California officials basically wrote the Farm Worker Movement a blank check.State officials waived competitive bidding requirements to give La Union del Pueblo Entero a $2.2-million contract to educate farmworker parents, saying the group’s extensive community network in eight counties made it the only organization equipped to do the job.

In fact, LUPE did not even have an office in any of the counties.

Then the Texas-based group demanded the first year’s state money upfront to start the California program, which provides information and referrals to farmworker parents with preschool children.

The California First Five Commission agreed to advance money each quarter and have LUPE account for it later — the first time the commission had made such an arrangement since it began operating in 1999, according to the then-director.

After the first nine months, the charity stopped submitting vouchers to back up its expenses and did not bother explaining how it spent the state money for almost a year (until The Times requested the documents).

What the community organizing group lacked in on-the-ground operations it made up for with political cachet, which helped the proposal sail through the commission chaired by actor and director Rob Reiner.

Reiner said he believed LUPE was uniquely qualified to reach migrant farmworkers, a difficult group to educate about available services.

“This is something they were set up to do. They were the only ones,” he said in an interview.

In 2003, Nora Benavides, then development director for the Service Center, heard the commission had money available to help migrant children. She approached commissioners, telling them the Farm Worker Movement could help.

“The commission said, ‘We think the Farm Worker Movement can play a vital role to impact farmworkers. The eagle represents Cesar Chavez, and we know that the eagle represents an incredible amount of dignity to farmworkers,’ ” she recalled.

Jane Henderson, then executive director of the First Five Commission, said Benavides worked with Esperanza Ross, the registered lobbyist for the UFW, who helped persuade commission members to award LUPE the four-year contract.

Henderson knew Ross as the union’s lobbyist. When LUPE moved into California, however, Ross took on a second role: She has been working as LUPE’s policy director, augmenting the $30,250 the union paid her to lobby in 2004. Experts said she must be careful to balance the two roles, since lobbyists are permitted to engage in political activity that charities are barred from.

In 2004, LUPE spent almost 40% of the state grant on various arms of the Farm Worker Movement, according to state records. Among the beneficiaries:

The UFW was paid $17,166 to handle accounting and human resources, $463 for posters and pins with the UFW logo and $300 for a booth at the union convention.

The Service Center was paid $47,250 for consulting, to help LUPE comply with state regulations.

The Farmworker Institute for Education and Leadership Development was paid $50,000 to write 10 30-second educational radio blurbs and develop a program to train parent leaders.

The UFW-affiliated radio studios were paid $9,300 for production, and then each of the four California radio stations the movement owns earned $375 per hour to air one-hour programs required by the grant.

The Farm Worker Movement’s radio stations were even paid to air public service announcements, with rates ranging from $11 to $75 per 30-second spot.

During one week in December 2004, Radio Campesina billed $2,295 to do 85 promotions for an upcoming event, charging $27 for each 30-second promotion. Then it charged $5,000 for 90 minutes of live broadcasts from the event.

Paul Chavez, who oversees the radio stations and also sits on the board of LUPE, said the network doesn’t usually charge for public service announcements unless groups come in with a budget: “It’s really whatever the market can bear.”

The checks are cut by the UFW’s accounting office, run by Elizabeth Villarino, who is also the treasurer of LUPE.

To meet the goal of the program funded by the First Five Commission, LUPE set up committees of farmworker parents, educated them about their preschool children’s needs and helped them sign up for existing programs, such as health insurance.

Once organizers had set up the committees and compiled a database of parents, half a dozen organizers said, Benavides told them to start signing the parents up as LUPE members and charging a $40 annual fee. When staffers objected, they said, they were forced out.

Benavides, who became LUPE’s executive director in August 2004, agreed that the organizers were reluctant to ask for membership dues, which she said are vital to making programs self-sustaining and making sure members feel invested in LUPE.

“Some people just aren’t comfortable asking for money,” she said, adding that she fired a number of staff members because they did not meet various goals, including that one.

When state officials monitoring the grant raised questions about the staff turnover and the push for members, UFW President Arturo Rodriguez, also the president of LUPE, tried to reach Reiner to complain.

Some LUPE staff members said they objected that it was wrong to collect dues for programs that were already paid for by the state grant. In some cases, they said they’d assured parents there would be no fee.

“We didn’t need the money,” said Cesar Lara, LUPE’s California director until he resigned under pressure in July. “And we weren’t offering any services.”

Vista del Monte Project: a Loan Among Friends

Tenants in the apartment complex perched high in the San Francisco hills had stunning views of the bay, but in 2000 they were about to be evicted. Then the National Farm Workers Service Center bought the 104-unit building on Gold Mine Drive with a low-interest loan from the California Housing Finance Agency and a promise to keep the rents affordable.To swing the deal, Paul Chavez, president of the Service Center, needed to borrow an additional $1.2 million to help renovate the complex. So he turned to the Cesar E. Chavez Community Development Fund, a foundation he also chairs.

Chavez said he presented the deal to the foundation board and recused himself from the vote on the loan. The result was a $1.2 million note at 11.75% interest, far higher than any of the Service Center’s many other notes or loans for affordable housing projects.

“That’s the amount that was needed to entice the fund to come in,” Chavez said, noting the Chavez Fund had to liquidate other investments in order to make the loan.

Chavez acknowledged divided loyalties. As head of the Service Center, he said, “I’ve got to make sure that the deal pencils out.” On the other hand, he said, “In my mind it’s got to be at a higher rate than you might be able to get on the street, just to make sure that there aren’t any appearances of impropriety or anything like that.”

Along with purchasing the Vista del Monte complex, the Service Center embarked on extensive repairs. The rehabilitation ran into trouble right away. Apartments flooded when the roof was being repaired, mold grew, tenants were displaced and the contractor repeatedly asked for changes that increased the price.

Jon Orovecz, the consultant hired by the California Housing Finance Agency to oversee construction, complained frequently that prices exceeded industry standards and that the Service Center officials were agreeing to unnecessary costs.

“Never in my 25-year career have I seen anything as ridiculous,” he wrote in May 2002. “ A lot of money has been wasted due to a failure to understand what things really cost and to intelligently explore other alternatives.”

When the state agency, with $11.4 million invested at 5.9% interest, found out the Service Center was making payments on the Chavez fund loan, officials ordered it to stop immediately because the project was over budget.

State officials warned repeatedly that the payments to the Chavez fund were unauthorized, but to no avail.

According to notes of one meeting, the Service Center’s general counsel, Emilio Huerta, insisted the payments were essential.

“Per EH, they need to continue payments. The major reason provided was that they do not want to upset good relationship with C. Chavez Development for future financing needs,” the state loan officer wrote.

The close relationship between the two entities goes beyond the common leadership of Paul Chavez. The Chavez fund, with about $10 million in assets, is a foundation that must give a certain percentage of its earnings each year to designated charities. The main charity the fund supports each year, according to tax returns, is the Service Center.

Chavez Center: From Union Hub to Tourist Attraction

Hundreds of UFW workers used to live and work on the sprawling grounds of the former tuberculosis sanatorium in the Tehachapi Mountains, the union headquarters since 1971. Single staff members lived in the main building of the hospital, couples with children in the double-wide trailers. The massive, Mission-style North Unit housed offices and rooms for large events, from conferences to weddings.Today all the offices fit in one small building, and the compound is being transformed into a tourist attraction that lionizes Chavez and his accomplishments — and makes money for the movement he founded.

The tab: $5 million dollars in taxpayer money.

The methodology: All in the family.

When the state required matching funds to obtain a grant to transform the decrepit North Unit into the Chavez Learning Institute, the landlord offered to forgo the rent.

The Chavez Foundation, headed by Paul Chavez, gratefully accepted the offer from the Stonybrook Corp., headed by Paul Chavez.

To verify the multimillion-dollar value of the donation, the Chavez Foundation sent state officials a letter from a local real estate expert: Emilio Huerta, president of American Pacific Brokerage, confirmed the value of the building owned by the Stonybrook Corp., the charity Emilio Huerta serves as counsel and board secretary.

When state officials wanted an outside appraisal, the Chavez Foundation turned to Celestino Aguilar, a Fresno real estate maven Paul Chavez recently referred to as “Mr. Slick” in describing his role decades ago in helping Cesar Chavez get into the housing business.

State officials were satisfied that the offer to forgo rent met the requirement for raising matching dollars on the $2.5-million grant, said Diane Matsuda, executive officer of the California Cultural and Historical Endowment: “There’s the appearance maybe of some sort of self-dealing, but in this particular case we believe it was a genuine offer of the lease.”

The Chavez Foundation’s grant application stressed the historic value of the project, the Chavez library that will be created and the opportunity to tell the story of the Farm Worker Movement. In public appearances, family members stress that the retreat center will be available for rent, with rooms to stay overnight and catering done by Pan Y Vino, the cafeteria on campus that was once a communal kitchen. The Stonybrook Corp. has sole catering rights.

Two earlier state grants, an additional $2.57 million, were spent creating a memorial garden around Chavez’s grave and a visitor center with photo exhibits and a light-and-sound enhanced re-creation of his office. That area is already available for rent:

“When planning for a special event, you want to give your guests an out-of-the-ordinary experience that is truly unforgettable. And if you are like most people, you look for a venue that will excite, inspire, entertain, and delight everyone on your list,” reads an advertisement by the Chavez Foundation. “The National Chavez Center — the historic headquarters and final resting place of the late civil rights and farm labor leader Cesar Chavez — is the perfect setting for a wedding, or an outdoor festival.”

The project ran 50% over budget, yet two state audits found no problem, even though there was no written documentation explaining the overruns. In his last days in office, Gov. Gray Davis gave the foundation an additional $600,000 to help plug the gap.

Sixty-four percent of the money spent on construction went to nonunion firms, Paul Chavez said, adding that it was difficult to find unionized companies willing to bid on the project.

On Cesar Chavez’s birthday last March, volunteers gathered to fill dumpsters with garbage they carted out of the abandoned North Unit, soon to become a shrine to the movement’s history. Grape boycott posters, index cards listing unfair labor practice cases, associate UFW membership applications and old Christmas cards fluttered away in a stiff wind, unwanted history jettisoned along with the furniture and debris.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

A family of nonprofits

About a dozen children and grandchildren of United Farm Workers union founder Cesar E. Chavez work for the various entities that make up the Farm Worker Movement. Those with multiple roles draw a single salary from one group, as noted where available. Here’s a look:

Anthony (Son): Runs Radio Campesina ($87,908) and serves on National Farm Workers Service Center, Stonybrook Corp. and Cesar E. Chavez Foundation boards

Anthony married Anna

Anna: Service Center Finance Department

Cesar L. Chavez (Grandchild): Engineer of a Radio Campesina station

Robert Chavez (Grandchild): Asst. radio engineer

---

Paul (Son): Service Center president ($124,046); Stonybrook president; chairs the Cesar E. Chavez Community Development Fund and the Chavez Foundation; Civic Empowerment Coalition board secretary, and La Union del Pueblo Entero (LUPE) board member

---

Eloise Chavez Carrillo (Daughter): Chavez Foundation board member (unpaid position)

Bernadette Farinas (Grandchild): National Chavez Center site administrator

---

Elizabeth (Daughter): UFW controller ($62,237); LUPE and Chavez Foundation treasurer

Elizabeth married David Villarino

David Villarino: Farmworker Institute for Education and Leadership Development executive director ($77,996), and Service Center board member

---

Sylvia (Daughter): Chavez Foundation board member (unpaid position)

Sylvia married George Delgado

Christine Delgado (Grandchild): UFW political director ($44,339), resigned to run for California Assembly

Teresa Delgado (Grandchild): Until recently, ran Chavez Foundation programs at UFW headquarters

Rodolfo Delgado (George’s brother): Runs Stonybrook

---

Arturo Rodriguez (Widowed son-in-law): UFW president ($77,890); president of the Farmworker Institute, the Civic Coalition, UFW Foundation and LUPE; board member of Chavez Foundation, union pension and health funds

Julie Rodriguez (Grandchild): Chavez Foundation programs director

Andres Irlando (Daughter’s son-in-law): Until recently, the Chavez Foundation president ($114,151)

Sonia Hernandez (Rodriguez’s fiancee): Service Center’s Education Initiatives director

*****

The Farm Worker Movement

Here are the main tax-exempt entities that grew out of the United Farm Workers’ drive to organize farm laborers.*

Arturo Rodriguez presides over:

United Farm Workers

Labor union representing primarily farmworkers.

Budget

Net assets: $1,523,066

Revenue: $6,638,329

Expenses: $7,216,385

----

UFW Foundation

Formerly the National Farm Workers Health Group, which funded health clinics; now a charity searching for a mission; may focus on immigration initiatives.

Budget

Net assets: $350,862

Revenue: $2,920

Expenses: $19,782

----

Civic Empowerment Coalition

Formed last year to collect money from farmworkers and UFW members and spend it on political causes.

Budget

Net assets: $4,353

Revenue: $10

Expenses: $25,059

----

Farmworker Institute for Education and Leadership Development

Obtains state, federal and local grants to do research and train farm laborers and other Latino workers; runs English classes for Spanish speakers.

Budget

Net assets: $73,303

Revenue: $1,428,940

Expenses: $1,442,744

----

La Union del Pueblo Entero

Community organizing group, primarily in Texas, lobbies for street lights and other services in poor areas. Expanded into California in 2004 with California Endowment and state funding.

Budget

Net assets: $16,797

Revenue: $1,837,890

Expenses: $1,626,458

----

Paul Chavez presides over:

National Farm Workers Service Center

Builds and manages affordable housing projects; operates the nine-station Radio Campesina; launching educational initiative for Latino youths. It also forms other nonprofits for individual housing projects.

Budget

Net assets: $24,593,728

Revenue: $16,273,635

Expenses: $10,995,747

----

Stonybrook Corp.

Owns and manages property, including UFW headquarters; provides maintenance and food service. Recently acquired the Keene Store, a diner just outside UFW headquarters.

Budget

Net assets: $2,131,146

Revenue: $763,379

Expenses: $1,053,263

----

Cesar E. Chavez Foundation

Established after Chavez died in 1993 to promote his legacy; has focused on educational initiatives and on establishing a visitor center, memorial garden and retreat facility at UFW headquarters.

Budget

Net assets: $3,672,514

Revenue: $2,542,519

Expenses: $1,088,516

----

Cesar E. Chavez Community Development Fund

Formerly the Martin Luther King Farm Worker Fund, a farmworkers services foundation set up with employer donations. Now provides loans for Service Center housing projects and supports the Service Center, the Chavez Foundation and other related charities.

Budget

Net assets: $9,817,031

Revenue: $1,212,910

Expenses: $638,059

----

Other organizations

Juan de la Cruz Pension Plan

Pension plan administered by union-management board. It has difficulty finding eligible retirees. It pays pensions to 2,411 retirees and receives payments for about 3,500 participants, mostly unionized farmworkers and several hundred Farm Worker Movement employees.

Budget

Net assets: $102.7 million

Expenses: Yearly administrative costs: $1.5 million, about one-third as much as the $4.6 million it gives out

----

Robert F. Kennedy Medical Plan

Designed for farmworkers with seasonal employment; now covers fewer than 3,000 workers during peak season, including several hundred employees of the UFW and its affiliates. The plan is administered by a staff working at UFW headquarters; the board includes union and management trustees.

Budget

Net assets: $7,953,676

Expenses: $10.5 million in benefits

----

*The financial data are the most recent available, generally for the 2004 calendar year. Assets are as of Dec. 31, 2004, except for the Chavez Foundation and the Farmworker Institute, which are for July 1, 2004.

Sources: IRS 990 forms, U.S. Department of Labor’s Form LM2 Labor Organization Annual Report and Form 5500 Annual Return/Report of Employee Benefit Plan, and Times reporting

Graphics reporting by Miriam Pawel

*

About This Series

Sunday: The UFW betrays its legacy as farmworkers struggle.

Today: The family business: Insiders benefit amid a complex web of charities.

Tuesday: The roots of today’s problems go back three decades.

Wednesday: A UFW success story — but not in the fields.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.