Candidate Shriver wants overhaul of L.A. County campaign finance laws

- Share via

Bobby Shriver, the first Los Angeles County supervisorial contender in 18 years to opt out of voluntary campaign spending limits, is calling for a major overhaul of county election laws, including lifting fundraising restrictions on candidates who use personal wealth to help pay for their campaigns.

Last month, the Santa Monica lawyer and nonprofit director contributed $300,000 of his own money to his effort to succeed longtime west county Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky. Shriver, a member of the Kennedy political family, criticized a $1.4-million voluntary spending limit in the June 3 primary as inadequate to get his message out to 2 million constituents.

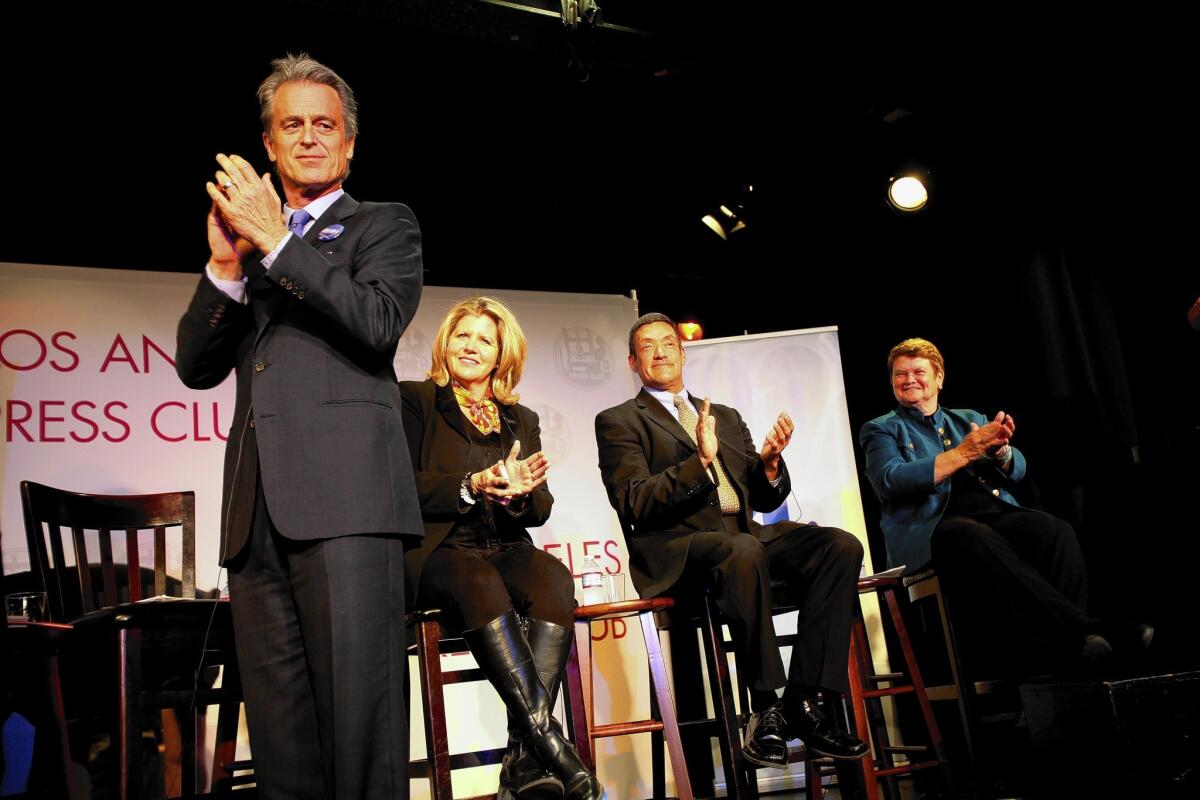

Speaking last week at a debate at Temple Israel in Hollywood, Shriver said he’d be willing to put even more of his money into the campaign, if necessary. “If I felt I had to tell my story, sure,’’ he said in response to a question. “Particularly if I felt I got attacked on an unfair basis.”

Spending limits have become one of the clearer points of separation for the top three candidates in the race. Shriver has called the county’s current campaign finance laws outdated and probably unconstitutional. But his most prominent rivals, former state lawmaker Sheila Kuehl and West Hollywood Councilman John Duran, also lawyers, have said the county’s campaign spending laws are working and the voluntary cap on expenditures is sufficient to mount a credible campaign.

Under existing rules, candidates who abide by a $1.4-million spending limit can collect individual donations of up to $1,500.

But if a candidate rejects the voluntary spending cap and makes large personal contributions — as Shriver did in early March — he or she is restricted to maximum donations of $300. At that point, all other candidates in the race can begin raising individual donations in unlimited amounts. Shriver says that unfairly punishes those who self-fund bids for public office.

Shriver’s criticism of the campaign law comes as a package of 1996 reforms is facing its first real test. After decades of little movement on the Board of Supervisors, terms limits are pushing out Yaroslavsky and Supervisor Gloria Molina this year, followed by Don Knabe and Michael D. Antonovich in 2016.

New leadership could usher in changes on a number of policy fronts in the county, including how political spending is regulated.

Experts in campaign finance law say portions of the county’s law may be vulnerable to legal attack because of recent U.S. Supreme Court rulings. The high court has repeatedly struck down limits on political spending, saying they infringe on free speech. A 1996 state campaign finance law with provisions similar to the county restrictions was invalidated by a federal court.

“There could be a legitimate case made against’’ the county rules, said Robert Stern, former president of the Center for Governmental Studies, which analyzes campaign finance laws. “But as long as no one challenges it, it remains law.

Some analysts say Shriver could run the risk of alienating voters who supported the county campaign reforms, coauthored by Yaroslavsky and former Supervisor Yvonne Burke. But Shriver’s political consultant, Bill Carrick, said his candidate has received sympathetic reactions when voters hear he was limited to $300 per donor.

Shriver favors regulations on campaign fundraising, Carrick said, but wants more “realistic” rules that account for the cost of buying TV ads, radio spots and mailers. Shriver says he will seek guidance from a panel of experts before introducing election law changes.

In 2008, Carrick said, Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas spent $1.3 million to win his seat. But a coalition of labor groups supporting him — who by law can spend unlimited amounts — put more than $8 million into the effort to elect him. “You have to have a system that is constitutionally balanced, that will allow everybody to raise money under the same rules,’’ Carrick said.

Kuehl said the current county law is appropriate and takes a carrot-and-stick-approach, encouraging spending limits but not requiring them. She questioned how that could be illegal. “The county offers each candidate a choice,” Kuehl said. “Mr. Shriver has chosen not to limit his spending and therefore he can’t complain that the county forced him to accept lower contributions.”

The most recent campaign finance statements show that as of mid-March, Shriver led in fundraising, partly as a result of his six-figure personal donation. In all, Shriver reported collecting $848,000. Kuehl collected $717,000, including donations of $20,000 from William Resnick, a retired Los Angeles psychiatrist, and $75,000 from the California Nurses Assn. after the limits were lifted as a result of Shriver’s action. Duran reported collecting $187,000.

Duran said his greater concern with county campaign expenditures was being able to track contributions in a timely manner. Candidates aren’t required to file finance statements electronically, which delays posting of information on the county’s website by days and sometimes weeks.

Tracking activity by independent committees that can spend unlimited amounts trying to influence elections is even tougher, he said. By contrast, he said, the city of Los Angeles’ Ethics Commission operates a campaign finance website that is frequently updated and relatively easy to use.

“The county’s systems are antiquated,’’ he said at a recent debate in Hollywood. “They are ineffective.”

Yaroslavsky, for one, thinks the law he helped write still works. It was intended to level the playing field for candidates who can’t write themselves a big check, he said. Shriver, the supervisor said, “still has a distinct advantage over the other candidates.”

“I understand his frustration,” Yaroslavsky said. “But the rest of the candidates don’t have the options he has.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.