On the Offensive Against an Array of Suspected Foes

- Share via

“Never treat a war like a skirmish. Treat all skirmishes like wars.” --L. Ron Hubbard

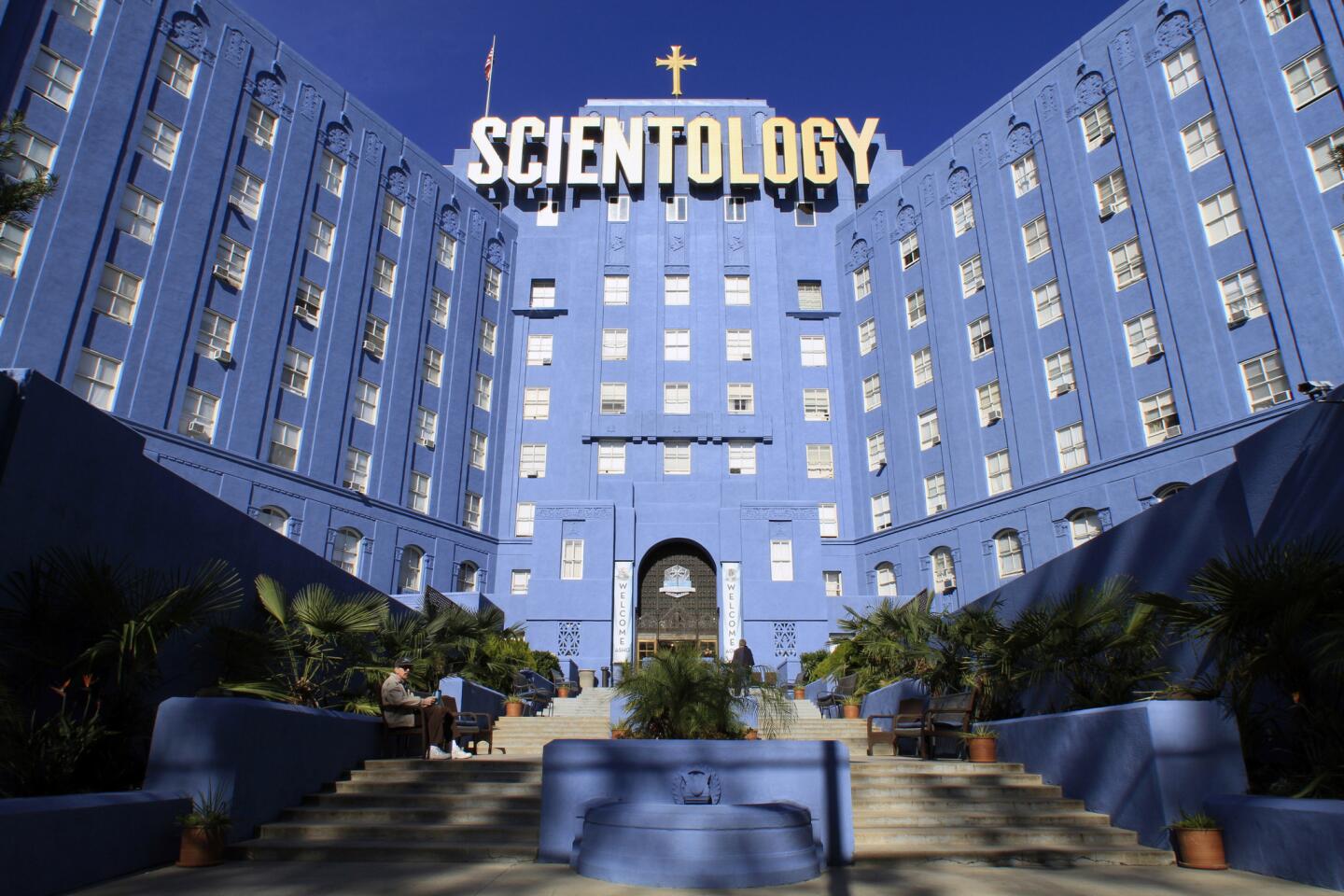

The Church of Scientology does not turn the other cheek.

Ministers mingle with private detectives. “Sacred scriptures” counsel the virtues of combativeness. Parishioners double as paralegals for litigious church attorneys.

Consider the passage that a prominent Scientology minister selected from the religion’s scriptures, authored by the late L. Ron Hubbard, to inspire the faithful during a gala church event.

“People attack Scientology,” the minister quoted Hubbard as saying. “I never forget it; always even the score.”

The crowd cheered.

As far back as 1959, Hubbard warned that illness and even death can befall those seeking to impede Scientology, known within the church as “suppressive persons.”

“Literally, it kills them,” Hubbard wrote, “and if you don’t believe me I can show you the long death list.”

He told the story of an electrician who bilked the organization. “Within a few weeks,” Hubbard said, “he contracted TB.”

Scientology seems committed not only to fighting back, but to chilling potential opposition. For years, the church has been accused of employing psychological warfare, dirty tricks and harassment-by-lawsuit to silence its adversaries.

The church has spent millions to investigate and sue writers, government officials, disaffected ex-members and others loosely defined as “enemies.”

Teams of private detectives have been dispatched to the far corners of the world to spy on critics and rummage through their personal lives--and trash cans--for information to discredit them.

During one investigation, headed by a former Los Angeles police sergeant, the church paid tens of thousands of dollars to reputed organized crime figures and con men for information linking a leading church opponent to a crime that it turned out he did not commit.

Early last year, an American Scientologist was arrested in Spain for possessing dossiers containing confidential information on a member of Parliament and a Madrid judge who is oversaw a fraud and tax evasion probe of the church. The dossiers included personal bank records and family photographs, according to press accounts.

Before a British author’s critical biography of Hubbard was even released two years ago in Europe, the church had him and his publisher tied up in a London court for alleged copyright infringement. The writer speculated that Scientology sympathizers had somehow managed to obtain pre-publication proofs of the book.

Scientology spokesmen insist that the organization is doing nothing illegal or unethical, and is merely exercising its constitutional rights with vigor.

They argue that Scientology has been targeted by hostile government and private forces--including the Internal Revenue Service, the FBI, the press, psychiatrists and unscrupulous attorneys--that have persecuted the church since its founding three decades ago.

As a matter of self-preservation, lamented Scientology attorney Earle C. Cooley, the church has been forced to fight back and then has been unfairly chastised for its aggressiveness.

“When we were attacked at Pearl Harbor we didn’t just sit back and defend there,” Cooley declared. “We tried to get out on the offensive as quickly as possible. . . . To sit back and ward off the blows is ridiculous.”

Underlying the church’s aggressive response to criticism is a belief that anyone who attacks Scientology is a criminal of some sort. “We do not find critics of Scientology who do not have criminal pasts,” Hubbard wrote back in 1967. “Over and over we prove this.”

When Scientology takes the offensive, L. Ron Hubbard’s writings provide the inspiration. Here is a sampling of what Hubbard wrote:

“The purpose of the (lawsuit) is to harass and discourage rather than win.”

“If attacked on some vulnerable point by anyone or anything or any organization, always find or manufacture enough threat against them to cause them to sue for peace. . . . Don’t ever defend. Always attack.”

“We do not want Scientology to be reported in the press, anywhere else than on the religious pages of newspapers. . . . Therefore, we should be very alert to sue for slander at the slightest chance so as to discourage the public presses from mentioning Scientology.”

“NEVER agree to an investigation of Scientology. Only agree to an investigation of the attackers. . . . Start feeding lurid, blood, sex crime, actual evidence on the attack to the press. Don’t ever tamely submit to an investigation of us. Make it rough, rough on attackers all the way.”

Obedience to these rules is not discretionary. They are scripture and, as such, have guided a succession of church leaders in their responses to perceived attacks.

Ironically, Hubbard’s doctrinal dictums have often served only to escalate conflicts and reinforce the cultish image the church has been trying to shake.

In the early 1970s, British lawmaker Sir John Foster offered a seemingly timeless observation on Scientology in a report to his government.

He wrote that “anyone whose attitude is such as Mr. Hubbard displays in his writings cannot be too surprised if the world treats him with suspicion rather than affection.”

Defeating its antagonists is considered so vital to the religion’s survival that the church has a unit whose mandate is to bring “hostile philosophies or societies into a state of complete compliance with the goals of Scientology.”

Called the Office of Special Affairs, its duties include developing legal strategy and countering outside threats.

Its predecessor was the Guardian Office, whose members became so overzealous that Hubbard’s wife and 10 other Scientologists were jailed for bugging and burglarizing U.S. government agencies in the 1970s.

Now, Scientology spokesmen say, attorneys are hired to handle conflicts with church adversaries to ensure that history does not repeat itself. The attorneys, they say, employ private detectives to help prepare court cases--a role that, in the past, would have been filled by Scientologists from the Guardian Office.

But some former Scientologists contend that the private detectives have simply replaced church members as agents of intimidation. The detectives are especially valued because they insulate the church from deceptive and potentially embarrassing investigative tactics that the church in fact endorses, according to this view.

One of the first private detectives hired by the church was Richard Bast of Washington, D.C.

In 1980, he investigated the sex life of U.S. District Judge James Richey, who was presiding over the criminal trial of Hubbard’s wife and the 10 other Scientologists. Richey had issued rulings unfavorable to them.

Bast’s investigators found a prostitute at the Brentwood Holiday Inn who claimed that Richey had purchased her services while staying at the hotel during trips to Los Angeles. Bast’s men gave her a lie detector test and videotaped her account.

That and other information obtained by Bast’s investigators was leaked to columnist Jack Anderson, and appeared in newspapers across the country. Soon after, Richey resigned from the case, citing health reasons.

In 1982, Bast surfaced again, this time in Clearwater, Fla., where the church’s secretive methods of operating had stirred community anxiety.

Bast’s detectives, posing as emissaries of a wealthy European industrialist, lured some of the community’s most prominent businessmen aboard a luxurious yacht. Their pitch: the industrialist wanted to invest $100 million in Clearwater’s decaying downtown.

But there was a catch, recalled developer Alan Bomstein, one of the businessmen being wooed. The emissaries said their boss was dismayed by the conflict between Clearwater and Scientology, and wanted the businessmen to help quash a public inquiry into the church’s activities.

When the businessmen refused, Bomstein said, the emissaries vanished. Two years later, Bast revealed the deception in a court declaration. He said the undercover operation was necessary to learn whether Clearwater’s elite were conspiring to run the church out of town.

More recently, Scientology investigations have been run by former Los Angeles Police Department sergeant Eugene Ingram, who was fired by the department in 1981 for allegedly running a house of prostitution and alerting a drug dealer of a planned raid. (In a later jury trial, Ingram was acquitted of all criminal charges.)

When he needs help, Ingram has sometimes turned to former LAPD colleagues.

Ex-officer Al Bei, for example, played a key role in a 1984 investigation of David Mayo, an influential Scientology defector who had opened a rival church near Santa Barbara. Scientologists believed Mayo was using stolen Hubbard teachings.

Bei and other investigators questioned local businessmen, handing out business cards that said, “Special Agent, Task Force on White Collar Crime.”

Their questions suggested--falsely--that Mayo was linked to international terrorism and drug smuggling, according to court records. At a local bank, Bei tried without success to obtain Mayo’s banking records and implied that Mayo was engaged in money laundering, an executive of the bank said.

The investigators rented an office directly above Mayo’s facility and leaned from the windows to photograph everyone who entered.

Mayo eventually obtained a court order barring Ingram Investigations and church members from going near Mayo or his facility. The judge said the investigation amounted to “harassment.”

On another occasion, Bei surfaced on a quiet residential street in Burbank, where he questioned neighbors of two highly critical former Scientologists, Fred and Valerie Stansfield. The Stansfields had established a competing center in their home to provide Scientology courses.

One of the neighbors said in a declaration that Bei attempted to “slander” the Stansfields with such questions as: “Did you know that Valerie told someone that she had pinworms two years ago?”

Los Angeles police officer Philip Rodriguez is another who has assisted Ingram in Scientology investigations.

In late 1984, he provided Ingram with a letter on plain stationery saying Ingram was authorized to covertly videotape a hostile former member suspected by church authorities of plotting illegal acts against the church.

Although the letter was written without official police department approval, Rodriguez’s action lent an air of legitimacy to the investigation. In fact, when church officials disclosed its results, they described the operation as “LAPD sanctioned”--a characterization that Police Chief Daryl F. Gates angrily disputed.

Rodriguez was suspended for six months for his role in the affair.

And when the clandestine videotapes were introduced in an Oregon court to discredit testimony by the former member, the presiding judge said: “I think they are devastating against the church. . . . It (the investigation) borders on entrapment more than it does on anything else.”

Another former LAPD officer, Charles Stapleton, worked part time for Ingram while teaching law at Los Angeles City College.

“Gene is a very thorough investigator,” Stapleton said in an interview. “He is determined to do the finest job he possibly can and he will employ whatever methods or tactics are necessary to do that job.”

Stapleton said he “bailed out” after Ingram asked him to tap telephones.

“Who’s going to know?” he quoted Ingram as saying.

“I will know,” Stapleton said he replied.

“I was told that if I didn’t want to do it, he knew somebody who would,” Stapleton said, adding that he did not know whether any telephones had, in fact, been monitored.

Ingram denied ever asking Stapleton to tap telephones.

“I’ve never done it and I’ve never asked anyone to do it,” Ingram said. “It’s just not worth it. It’s a crime. You’re going to get caught, so why do it?”

Ingram also said that he has not harassed anyone during his probes. He describes himself simply as “aggressive.”

“People who claim that I have conducted an improper investigation against them probably have so many things to hide,” said Ingram.

Church lawyer Cooley backed the investigator, saying: “I know of no impropriety that has ever been engaged in by Mr. Ingram or any other (private investigator) for the church. Mr. Ingram has done nothing wrong.”

Last year, Ingram and his colleagues surfaced in the small town of Newkirk, Okla., to investigate city officials and the local newspaper publisher. The publisher has been crusading against a controversial Scientology-backed drug treatment program called Narconon.

At the core of the dispute is a contention by publisher Bob Lobsinger that Narconon concealed its Scientology connection when it leased an abandoned school outside town to build the “world’s largest” drug rehabilitation center.

Lobsinger’s weekly newspaper has written about Scientology’s troubled past, and published internal documents on the drug program. In the process, he has helped rally community opposition.

Fighting back, Scientology attorneys in September mailed an “open letter” to many of Newkirk’s 2,500 residents announcing that Ingram had been hired to investigate Narconon’s adversaries. The letter said that “a few local individuals have sought to create intolerance by broadsiding the Churches of Scientology in stridently uncomplimentary terms.”

After arriving in town, Ingram tracked down the mayor’s 12-year-old son at the local public library, handed him a business card and told the boy to have his father call, Lobsinger said. “It was just a subtle bit of intimidation,” he said. “It certainly did not do the mother much good. She was very unnerved.”

Lobsinger said investigators also camped out at the local courthouse, where they searched public records for “dirt” on prominent local citizens.

“They were checking up on the banker, the president of the school board, the president of the Chamber of Commerce and, of course, the mayor and his family, and me,” Lobsinger said.

Newkirk Mayor Garry Bilger, who opposed the drug treatment program, said a man he believes was a church member tried to coax him into disclosing personal information. Bilger said the man showed up without an appointment and claimed that he was helping his daughter with a report on small-town government for a class at a nearby high school.

“He wanted to interview me and take pictures around the office but I didn’t allow that,” the mayor recalled. “Finally, I said, ‘Are you with Scientology or Narconon?’ He said, ‘I don’t know about those people.’ But he did, because he got outta there in a hurry.”

Before the man left, he gave Bilger the name of his daughter. The mayor then checked with the school system and was told that no such girl was enrolled.

“They have a standard pattern,” Bilger said of the Scientologists. “They try to be very aggressive. They try to intimidate. This is not the kind of atmosphere we need in the Newkirk community. . . . This tells me they are far from being harmless.”

Scientology critics contend that one church writing, above all others, has guided the organization and its operatives when they fight back. It is called the Fair Game Law.

Written by Hubbard in the mid-1960s, it states that anyone who impedes Scientology is “fair game” and can “be deprived of property or injured by any means by any Scientologist without any discipline of the Scientologist. May be tricked, sued or lied to or destroyed.”

Church spokesmen maintain that Hubbard rescinded the policy three years after it was written because its meaning had been twisted. What Hubbard actually meant, according to the spokesmen, was that Scientology will not protect ex-members from people in the outside world who try to trick, sue or destroy them.

But various judges and juries have concluded that while the actual labeling of persons as “fair game” was abandoned, the harassment continued unabated.

For example, a Los Angeles jury in 1986 said that Scientologists had employed fair game tactics against disaffected member Larry Wollersheim, driving him to the brink of financial and mental collapse. He was awarded $30 million. In July, the state Court of Appeal reduced the amount to $2.5 million but refused to overturn the case.

Wrote Justice Earl Johnson Jr.: “Scientology leaders made the deliberate decision to ruin Wollersheim economically and possibly psychologically. . . . Such conduct is too outrageous to be protected under the Constitution and too unworthy to be privileged under the law of torts.”

In a recent lawsuit, former Scientology attorney Joseph Yanny alleged that the church and its agents had implemented or plotted a broad array of fair-game measures against him and other critics, including intensive surveillance and dirty tricks.

Earlier this year, a Los Angeles Superior Court jury awarded Yanny $154,000 in legal fees that he said the church had refused to pay.

Among other things, Yanny said in his lawsuit that he attended a 1987 meeting at which top church officials and three private detectives discussed blackmailing Los Angeles attorney Charles O’Reilly, who won the multimillion-dollar jury award for Wollersheim.

According to Yanny, the plan was to steal O’Reilly’s medical records from the Betty Ford Clinic near Palm Springs, then exchange them for a promise from O’Reilly that he would “ease off” during the appeal process.

Yanny, who later had a bitter break with Scientology, said he objected and the idea was dropped. The church denies such a discussion ever took place.

“There is not a scintilla of independent evidence that Yanny’s counsel was ever sought for any illegal or fraudulent purpose,” church attorneys argued in court papers.

Numerous other church detractors have said in court documents and interviews that they, too, were victims of fair game tactics even after the policy supposedly was abandoned.

John G. Clark, an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, said he once criticized the church during testimony before the Vermont legislature. Scientology “agents” retaliated, Clark alleged in a 1985 lawsuit, by trying to destroy his reputation and career.

He said in the lawsuit that they filed groundless complaints against him with government agencies, posed as clients to infiltrate his office, dug through his trash, implied that he slept with female patients and offered a $25,000 reward for information that would put him in jail.

“My sin,” Clark said in an interview, “was publicly saying this is a dangerous and harmful cult. They did a good job of showing I’m right.”

Scientologists, for their part, have described Clark as a “professional deprogrammer,” who in court cases has diagnosed members of religious sects as mentally ill without conducting direct examinations of them. They have branded his professional work as fraudulent and his psychiatric theories as “childish and nonsensical.”

In the words of one Scientology spokesman: “It’s a crime that he’s walking on the street right now.”

In 1988, the church paid Clark an undisclosed sum to drop his lawsuit. In exchange for the money, Clark agreed never again to publicly criticize Scientology.

On the opposite coast, psychiatrist Louis (Jolly) West, who formerly directed UCLA’s Neuropsychiatric Institute, said he also has felt the wrath of Scientology.

West, an expert on thought control techniques, said his problems began in 1980 after he published a psychiatric textbook that called Scientology a cult.

West said Scientology attempted to get him fired by writing letters to university officials suggesting that he is a CIA-backed fascist who has advocated genocide and castration of minorities to curb crime.

He said Scientologists once managed to get inside a downtown Los Angeles banquet room before guests arrived for a dinner celebrating the Neuropsychiatric Institute’s 25th anniversary. On each plate, West said, was placed “an obscenely vicious diatribe” against him and the institute--neatly tied with a pink ribbon.

So consumed are some Scientologists by their zeal to punish foes that they have violated the confidentiality of one of the religion’s most sacred practices, according to a number of former members.

These former members accuse others in the church of culling confessional folders for information that can be used to embarrass, discredit or blackmail hostile defectors--a practice once called “repugnant and outrageous” by a Los Angeles Superior Court judge. Some of these former members say they themselves took part in the practice.

The confidential folders contain the parishioners’ most intimate secrets, disclosed during one-on-one counseling sessions that are supposed to help devotees unburden their spirits. The church retains the folders even after a member leaves.

Last year, former church attorney Yanny said in a sworn declaration that he was fed information from confessional folders to help him question former members during pretrial proceedings. Yanny said he complained but was informed by two Scientology executives that it was “standard practice.”

Church executives have steadfastly denied that the confidentiality of the folders has been breached. They maintain that “auditors”--Scientologists who counsel other members--must abide by a code of conduct in which they promise never to divulge secrets revealed to them “for punishment or personal gain.”

“And that trust,” the code states, “is sacred and never to be betrayed.”

Often, those who buck the church say their lives are suddenly troubled by unexplained and untraceable events, ranging from hang-up telephone calls to the mysterious deaths of pets.

Los Angeles attorney Leta Schlosser, for one, said someone developed “an unusual interest” in her car trunk while she was part of the legal team in the Wollersheim suit against Scientology. She said it was broken into at least seven times.

She said her co-counsel, O’Reilly, discovered a tape recorder, wired to his telephone line, hidden beneath some bushes outside his home.

Then there is the British author, Russell Miller. After his biography of Hubbard was published, an anonymous caller to police implicated him in the unsolved ax-slaying of a South London private eye.

Miller was interrogated by two detectives, who concluded that he was innocent. Det. Sgt. Malcolm Davidson of Scotland Yard told the Los Angeles Times that the caller “caused us to waste a lot of time investigating” and “caused Mr. Miller some embarrassment.”

There is no evidence that ties the church to any of these incidents, and Scientology officials deny involvement in clandestine harassment or illegal activities. They suggest that church foes may themselves be responsible as part of an effort to discredit Scientology.

Today, the Scientology movement is engaged in a sweeping effort to gain influence across a broad swath of society, from schools to businesses, in hopes of winning converts and creating a hospitable environment for church expansion.

And Hubbard’s followers apparently consider his theology of combat an important component.

In 1987, they elevated to high doctrine a warning he wrote two decades ago in a Scientology newspaper, addressed to “people who seek to stop us.”

“If you oppose Scientology we promptly look up--and will find and expose--your crimes,” he wrote. “If you leave us alone we will leave you alone. It’s very simple. Even a fool can grasp that.

“And don’t underrate our ability to carry it out. . . . Those who try to make life difficult for us are at once at risk.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.