A census undercount could cost California billions — and L.A. is famously hard to track

- Share via

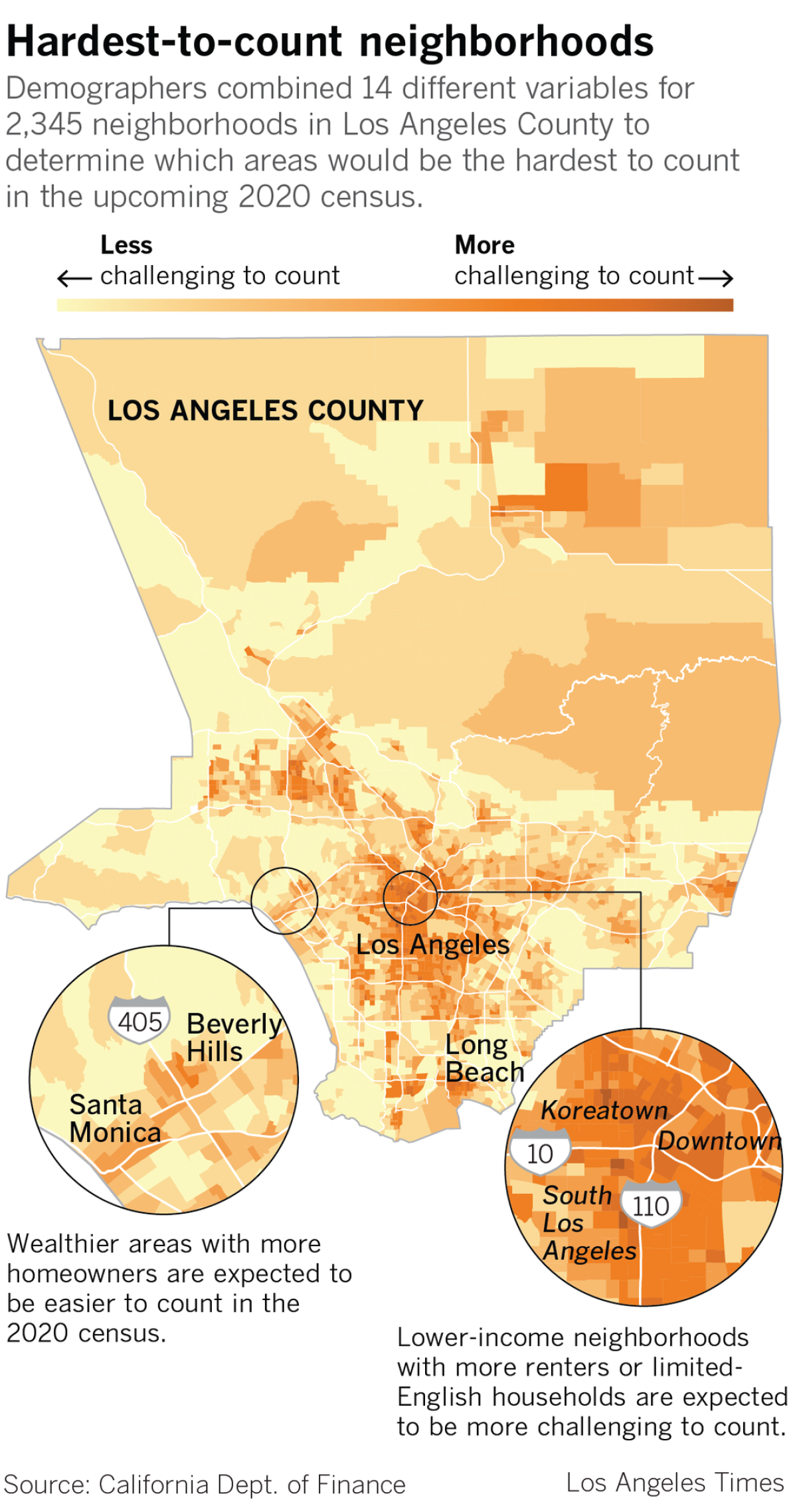

When it comes to the U.S. census, residents of Los Angeles County are notoriously difficult to track down.

The county, officials say, will be the nation’s hardest to tally because of its high concentrations of renters and homeless people, as well as immigrant communities that may not participate, because of language barriers or because they fear reprisal from the federal government — especially if a citizenship question is added to the form.

Many believe that appears likely. Last week, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority seemed ready to uphold the Trump administration’s plan to add the question. The court’s decision is expected in June.

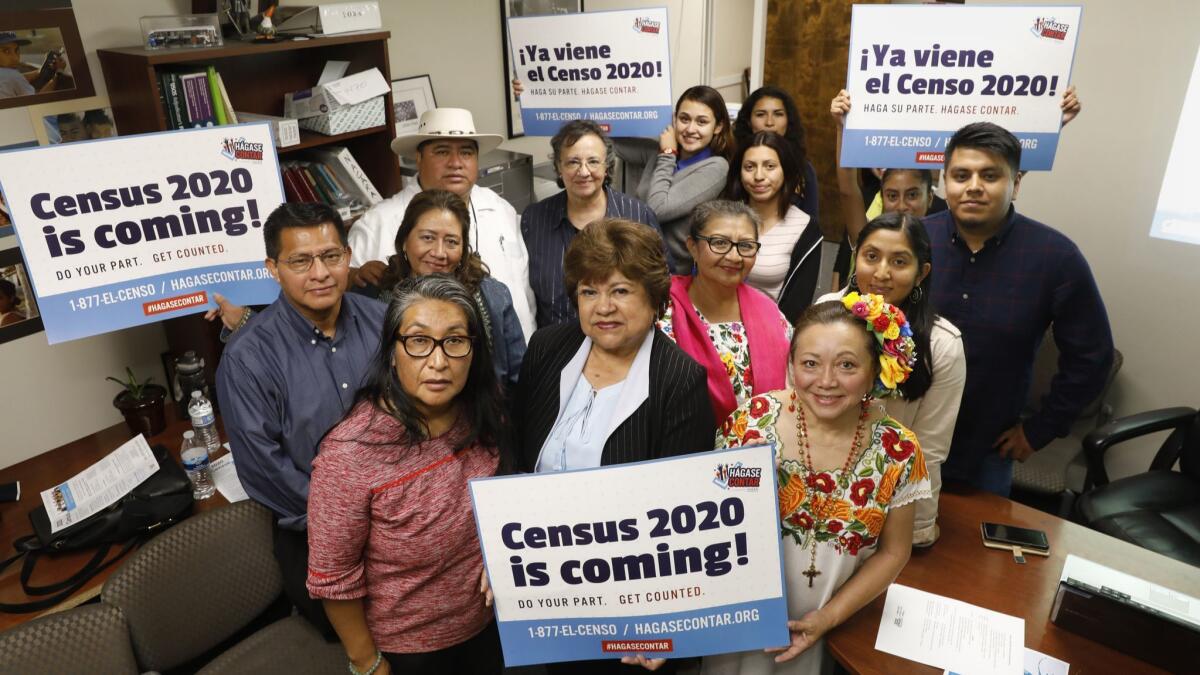

Already, census workers, community organizations and local politicians have started outreach efforts to ensure an accurate tally in next year’s count. At stake nationally are nearly $800 billion in federal tax dollars, political redistricting and the reapportionment of seats that each state is allocated in the U.S. House of Representatives.

In Los Angeles, home to the largest hard-to-count population in the nation, ensuring participation is particularly important.

“We could stand to lose anywhere from one to two congressional seats, and that primarily impacts areas like southeast Los Angeles and the South Central area, where African American and Latino communities live,” said county Supervisor Hilda Solis, whose district includes some of the hardest-to-count areas.

State government leaders could spend more than $150 million through next year to help verify addresses and expand outreach efforts, according to California’s census office.

Still, there will be major hurdles. Those without reliable internet connections may be missed in a census for which much of the count will happen through online surveys.

Cities such as Maywood, Cudahy and Bell Gardens would be heavily affected by an undercount, Solis said.

“These are some of the poorest neighborhoods, the most polluted, the most underrepresented in our system,” she said.

People worry that la migra will get them. They say, ‘If that’s the case, then forget it. I would rather be invisible.’

— Policarpo Chaj, director of a Mayan community group

Many of the services that people rely on in Los Angeles — such as nutrition programs and housing assistance — are tied to funds from the census. Statewide, 72% of the population belongs to one or another historically undercounted group.

“The biggest hurdle we have is for people to feel the data they will give the census will not come back in some way to hurt them,” said Arturo Vargas, chief executive of NALEO Educational Fund. “So we have been pushing that the information you give on the census is confidential.”

Renters are especially difficult to track, particularly in dwellings with non-family members. If the apartment has more people than a landlord allows, they may refuse to answer any questions.

“I’m not that worried about Beverly Hills or Palos Verdes Estates,” Vargas said.

On a recent Friday night, Policarpo Chaj crowded into a small Westlake office and cast his gaze on the projection ahead. He listened as a female census worker explained the importance of participating in the decennial count.

“It’s about fair representation,” the census worker said in Spanish.

Chaj and other Mayan community members had gathered to learn more about ensuring that Latinos fill out the form — and do so correctly.

A census coordinator told the group which questions would be included in the survey and assured them that it is illegal for any Census Bureau employee to disclose information that identifies a person or business.

“Credit card companies ask you for more information,” she joked.

Chaj, director of Maya Vision, said he understood the importance of his community being counted. But he noted that the Latino community is diverse and needs nuanced outreach. He suggested that the Census Bureau provide information in Mayan languages spoken in Mexico and Central America, such as Yucatec, Zapotec and K’iche’. Many in his community feel more comfortable speaking an indigenous language, he said, and speak Spanish as a second language.

A potential citizenship question also has put many immigrants and their families on edge, Chaj said.

“People worry that la migra will get them,” he said. “They say, ‘If that’s the case, then forget it. I would rather be invisible.’”

Sara Mijares, founder of the Mundo Maya Foundation, said including the citizenship question only would make Los Angeles harder to count.

“It’s going to affect not only undocumented immigrants, but American children of undocumented people who will not be counted,” she said.

Other areas of California with large minority populations, including parts of Orange and Riverside counties — as well as rural pockets of the state with hard-to-track addresses or limited internet access — will also prove difficult to count.

For every Californian missed by the census, L.A. County officials say, the state loses about $2,000 a year in federal program funding. California received some $115 billion through federal spending programs in fiscal year 2016, according to George Washington University — money that was guided by 2010 census data.

“For a family of five, that’s $100,000 that doesn’t come to the community” in 10 years, Mijares said. “But someone in that family has needs, from anything like using the parks at night to clinics that provide low-income services.”

Some grass-roots organizations have expressed concern that the communities they represent will disappear from the census count because they will be afraid to participate, lest the government use the information to track or deport them.

A report released Friday by the Council on American-Islamic Relations’ Los Angeles chapter found that many local Muslims were struck by the “invasiveness” of the questions on the census, including the proposed citizenship question. About 500,000 Muslims live in Southern California, according to CAIR.

RELATED: Are Arabs and Iranians white? Census says yes, but many disagree »

An Le, census lead for Asian Americans Advancing Justice, said that type of distrust is also prevalent among Asian immigrants and Pacific Islanders.

In January, a Census Bureau study on attitudes toward the census found that 41% of Asians said they were either “extremely concerned” or “very concerned” that their answers would be used against them. African Americans and Latinos followed closely behind, at 35% and 32%, respectively.

“There is a sizable portion of Asian immigrants that came after the last census, so that’s a factor,” Le said.

More than half a million Asian Americans live in the San Gabriel Valley alone, according to AAAJ.

Le said her organization looks beyond just the size of a community when it comes to census outreach, because it is less-represented ethnic groups — such as Cambodians — that often are harder to reach.

The group plans on using results from message testing to teach “trusted messengers” in the community how to speak to issues that will resonate “and figure out how we can dispel the myths about the census and allay anxiety or fears.”

The Census Bureau, Le said, provided education materials in five Asian languages — Chinese, Vietnamese, Tagalog, Japanese and Korean — but that won’t be enough.

“Smaller, ethnic media outlets are where people get news, and we need to develop relationships with them,” she said.

We have been pushing that the information you give on the census is confidential.

— Arturo Vargas, chief executive of the NALEO Educational Fund

California Calls, a coalition of community groups, recently created a program focusing on the census and redistricting in African American communities — another group that is at risk of an undercount.

“What’s most in our face is the amount of homelessness that L.A. is seeing, and we know that black folks are disproportionately affected by homelessness,” said Kevin Cosney, the organization’s special projects manager.

California Calls plans on teaming up with other groups and black churches to encourage census participation through phone banks, text message blasts, canvassing and social media campaigns, he said.

Black immigrants, he added, will be particularly hard to reach.

“Some, being Afro-Latino, would have the double whammy of a fear of government and how you’re treated as someone who presents as black on top of potential language barriers and a fear of deportation,” Cosney said.

For Basilio Hernandez, the importance of the census comes down to his children.

When he isn’t in school or working, Hernandez volunteers with the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles, focusing his attention on community outreach through workshops.

The group, which received state grants to work with immigrants and refugees on the census, launched a campaign called Contamos Contigo, or “We’re counting on you,” last week.

Hernandez has been meeting with students to explain how the census works and how participation can help fund the resources the students and their families rely on. He said he hopes that Los Angeles will get the money it needs in 2020 for programs such as Head Start and Section 8 housing.

“We’re going to have to work extra hard to make sure our community is counted,” he said. “We can’t be invisible out of fear.”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.