Why parking has gotten even tighter for disabled drivers in L.A.

- Share via

Beset with physical struggles that make it hard for her to get around, Del Hunter-White reached out a year ago to the Department of Disability about getting a curb painted blue and designated disabled parking in her Venice neighborhood.

After several weeks and daily calls, the 60-year-old, who has nabbed small roles in TV shows and commercials, got an employee on the phone who told her the parking program responsible for creating disabled parking in residential neighborhoods has not been active in seven years.

It was dispiriting news to Hunter-White, who said that in her densely populated, rapidly changing Abbot Kinney neighborhood it can be hard even for the able-bodied to find regular parking.

“I don’t want to be doom and gloom, but I am sometimes,” Hunter-White said. “Everything is a fight right now.… I don’t want to have to walk on bad knees and go searching for spots for four or five blocks.”

Although businesses and new apartments are required to provide a certain amount of disabled parking, officials from the Department of Transportation and Department of Disability said that the program that handled requests by residents was suspended in 2010 in the wake of the economic recession and budgetary problems.

Two years later, in 2012, changes in state and federal guidelines made it so that even if new parking spots were to be created, it would now be far more complicated to do so.

“Those guidelines, that apply to all cities, not just Los Angeles, stipulate that simply painting a blue curb and posting a sign on a street is no longer sufficient,” Paul Backstrom, a policy advisor to Councilman

More placards, more problems

There are 2.4 million permanent disabled parking placards in circulation in California. In L.A. County there were 785,438 permanent placards distributed as of Dec. 31, 2016, which is up from 596,430 placards in 2011.

But despite this increase, the number of spots on residential streets in that time has remained unchanged.

Misuse of these placards has sparked outrage among drivers in the state where issues over parking — and driving in general — frequently lead to daily dramas.

A recent audit found that California's Department of Motor Vehicles isn't doing enough to verify that applicants for disabled spots actually deserve them. The audit also revealed that nearly 26,000 placard holders were listed as being 100 years old or older — probably indicating that the DMV had failed to cancel the placards of people who had died.

On top of the issues revolving around the placards themselves, there’s the problem of where someone with a legitimate placard can find disabled parking.

“Non-disabled people don’t have an understanding or appreciation of the time and energy it takes for a disabled person with mobility issues to get through their day,” said Anastasia Bacigalupo, executive director at Westside Center for Independent Living, a community-based organization supporting disabled adults.

Studying the costs

In January, the L.A. City Council approved a six-month program to study how to once again create blue curb parking. Residents can now apply through the Department of Transportation, with the Department of Disability then assessing the validity of the request.

Geoffrey Straniere, a senior project coordinator for the Department of Disability, is tasked with vetting requests for new residential disabled parking spots.

He said that new requirements have made the creation of any new spots trickier and more expensive.

“You were just painting in the past, and now you’re literally demolishing, pouring, reforming and taking away parkways and medians and greenery to create a parking spot,” Straniere said. “This is where some of the difficulty comes in. So now I just can’t put paint, I have to put something down that might cost $70,000.”

Straniere is helping to put together a report that will examine issues like costs and logistics — and that could be presented to the City Council over the summer.

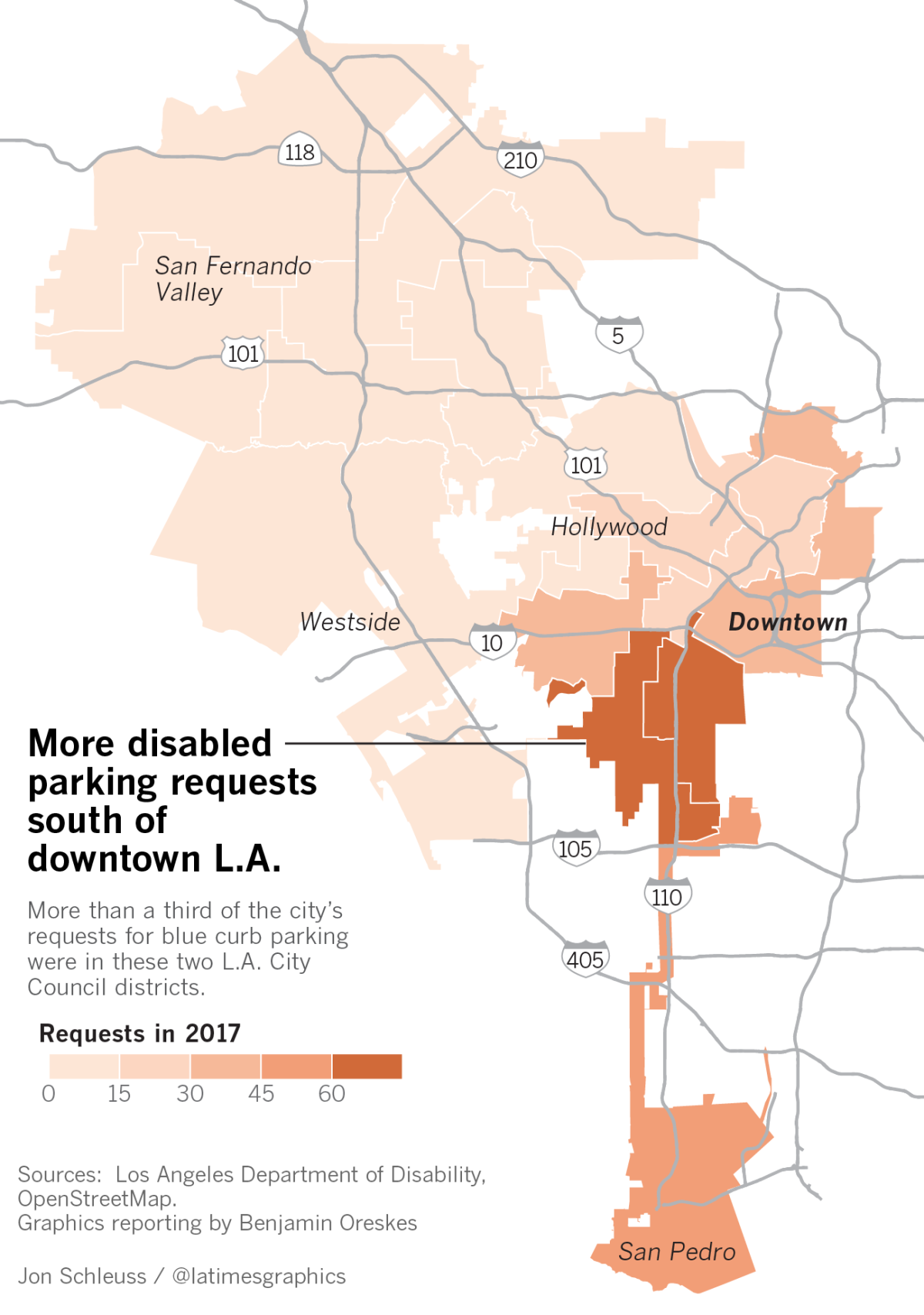

In the first five months of this year, the Department of Disability had received 382 requests for new blue curb parking, of which 349 were deemed valid. The agency declined to provide information about where exactly the requests came from, instead breaking them down by City Council districts.

Most of the requests came from districts representing South and Central Los Angeles. Crystal Killian, a 29-year veteran of the Department of Transportation, said a combination of low income and high population density leads to more demand for on-street parking in certain neighborhoods.

Killian said that many of the people who request disabled parking in their neighborhood are senior citizens on fixed incomes.

“The parking spaces on the street are always occupied,” Killian said. “So you always have to hunt for parking.”

How many of these blue-painted parking spots currently exist is a bit of a mystery.

The city used to track the number of traffic signs and curb zones, but Killian said that in the mid-1990s those data were lost, and the city never created a new database to capture that information.

Killian said the report that will be put together over the summer will address issues such as the cost of creating new disabled parking spots.

“I think we don’t understand how expensive it’s going to be. That, I think, is going to be some of the critical things that will come out of the study,” she said. “The overwhelming majority of locations I’ve looked at need physical construction.”

The quest for parking continues

Hunter-White likes to go out with her friends and enjoys regular games of tennis.

Despite trying to maintain an active lifestyle, she has struggled with nagging aches and pains from arthritis. It makes walking long distances a grind.

“Being in constant pain, I’ve adapted, but you don’t realize the amount of things you don’t do because the thought of pain is too much,” she said.

Her rent-controlled home is in a Venice bungalow complex. Most of the eight units are empty, except when they’re used by Airbnb renters.

Many of her old friends in the neighborhood are gone, replaced by young technology firm employees.

In this densely populated and busy environment, finding a parking spot she can use with her disabled placard has become increasingly difficult.

Venice is so congested on the weekends that Hunter-White said she relies on Lyft to get around out of concern that she will not be able to find a spot. The one blue curb spot nearby always seems occupied, she said.

In early 2017, Hunter-White was told she could submit an application for the creation of a new spot. She applied in March and a month later, on April 19, she was told her application appeared to be in order.

But Hunter-White said an employee from the Department of Disability also told her that the review process could go through several agencies.

And that could take a year.

da

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.