California’s in an exceptional earthquake drought. When will it end?

- Share via

California is in an earthquake drought.

It has been almost five years since the state experienced its last earthquake of magnitude 6 or stronger — in Napa. Southern California felt its last big quake on Easter Sunday 2010, and that shaker was actually centered across the border, causing the most damage in Mexicali.

Experts know this calm period will eventually end, with destructive results. They just don’t know when this well-documented geological pattern will shift.

“Earthquake rates are quite variable: We have a decade or two where we don’t have many earthquakes, and people expect that’s what California is always like,” said Elizabeth Cochran, seismologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. Eventually, “we’re going to dramatically see a change in earthquake rates.”

Scientists have been warning California of seismic dangers, be it the Big One on the San Andreas fault or catastrophes that could come from lesser-known faults, such as Hayward or Newport-Inglewood.

RELATED: Get ready for a major quake. What to do before — and during — a big one »

One reason for the urgent alerts: Memories of a truly destructive quake in many urban areas have faded. And with that, some fear, the urgency of pushing seismic safety has also faded.

Experts say California ignores these realities at its own peril.

“Along the main plate boundary faults, we are in a deficit of earthquakes in the last 100 years,” said Tom Rockwell, a San Diego State paleoseismologist. “At some point, that’s going to change. We’re going to have some big earthquakes.”

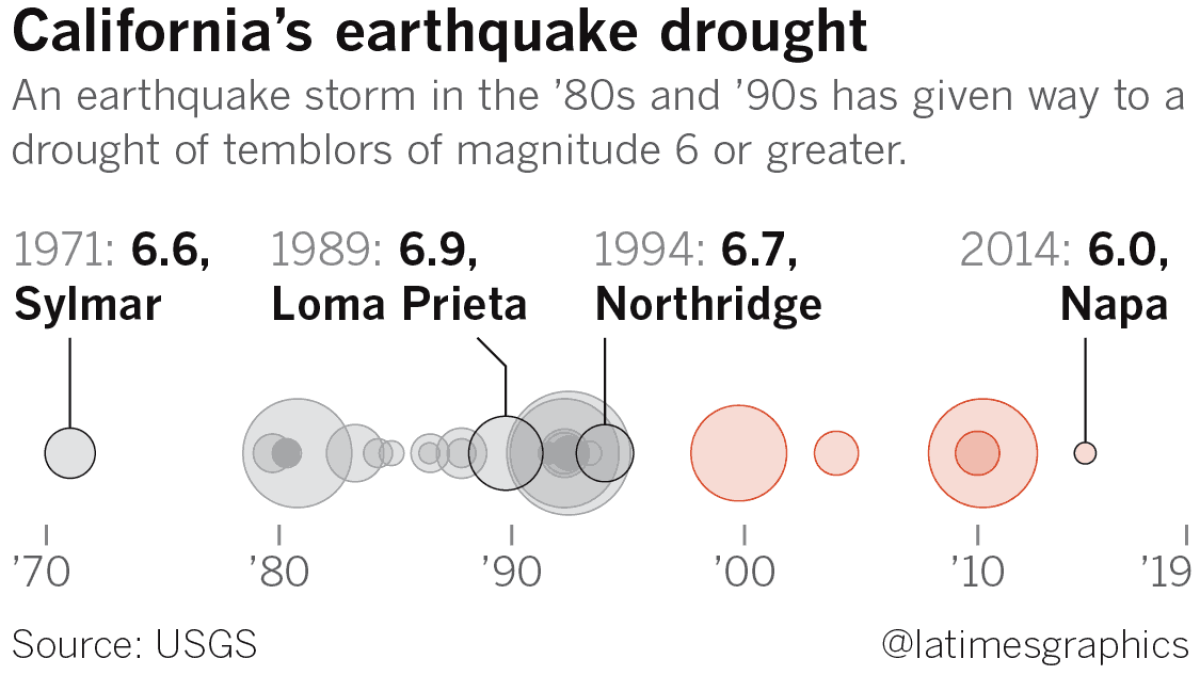

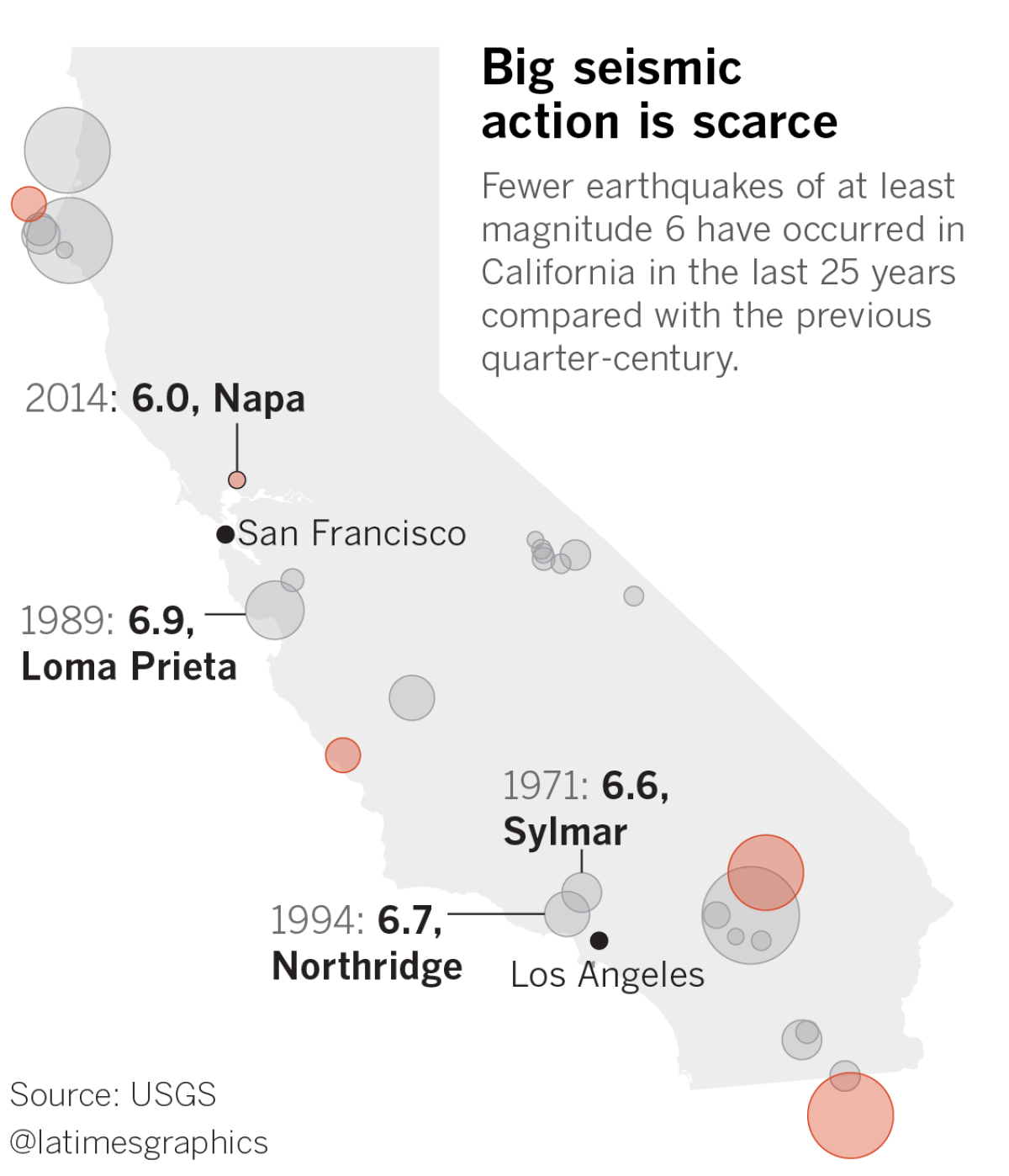

Consider how much quieter California has been in regard to earthquakes of magnitude 6 or greater:

• In the last 25 years, there have been 11 such temblors statewide. In the preceding generation, there were 32.

• In the last quarter-century, there have been three such earthquakes that shook California’s 10 southernmost counties. In the prior generation, there were nine, including the Sylmar temblor of 1971 (magnitude 6.6) and Northridge of 1994 (magnitude 6.7).

• The greater San Francisco Bay Area has been particularly quiet. Since the great 1906 earthquake destroyed much of San Francisco, there have been only three earthquakes of magnitude 6 or greater. But in the 75 years before that catastrophe, there were 14, according to geophysicist Ross Stein.

Earthquakes must happen at some point to relieve the immense tectonic forces that are pushing part of the state northwest toward Alaska and the rest southeast toward Mexico. On average, there’s about 12 feet of movement per century along the 730-mile San Andreas fault system between Point Arena in Mendocino County and the Mexican border, Rockwell said, but, except for a 90-mile section that creeps in San Benito and Monterey counties, there has been no significant movement along this primary boundary of faults between the Pacific and North American plates in a century.

There may be periods “where things get kind of all locked up and no earthquakes happen for a while. You store a lot of strain in the Earth’s crust,” said Tom Jordan, USC professor of geophysics. “Once it gets going, it’s like a set of dominoes. You might get multiple events if you have enough strain energy stored in the crust, because it’s been a long time since an earthquake.”

When a time of elevated seismic activity will come is hard to say. Some thought the 1989 magnitude 6.9 Loma Prieta earthquake, which killed 63 people, would mark the end of decades of seismic quiescence in the Bay Area. Instead, the lack of extreme shaking has largely persisted, save for the Napa temblor of 2014.

Scientists have been particularly focused on the lack of major seismic activity on several California faults that as a group produce the most frequent earthquakes on the plate boundary — the San Andreas, San Jacinto and Hayward. They are the ones seen as most likely to cause trouble in our lifetime.

Yet they’ve been exceedingly quiet. A USGS analysis published in the journal Seismological Research Letters Wednesday finds that, based on an analysis of sites where seismic data are known for the past millennium, the century between 1919 and 2018 is in all odds the only 100-year period in the past 1,000 years where there have been no earthquakes strong enough to break the ground on those three faults.

Ordinarily, there are roughly three to four of these earthquakes on these faults every 100 years.

“The next century is unlikely to be as quiet as this one. It’s hard to beat,” said USGS seismologist Glenn Biasi, the lead author of the study.

The 1800s, by comparison, was a far more active time for earthquakes. That century saw six large temblors on this trio of faults; between 1800 and 1918, there were eight. That’s an average of one major quake on those faults every 16 years.

Earthquake scientists have been buzzing for years about California’s hiatus in supersized earthquakes, thinking the chances of such a 100-year gap between ground-shattering seismic events to be improbable. “Did Someone Forget to Pay the Earthquake Bill?” was the title of a talk by UCLA geophysicist David Jackson at the Seismological Society of America conference in 2014.

RELATED: Say a major earthquake will hit in seconds. How do you protect yourself? »

Scientists focus on earthquakes that literally break the ground along the main plate boundary because they’re the ones that actually do the job of relieving centuries of tectonic strain. A famous example of the ground breaking was during the great 1906 earthquake that destroyed much of San Francisco; at Point Reyes in Marin County, a fence that intersected the fault was suddenly cut in two, separated on each side by the San Andreas by 18 feet.

Some quakes don’t do that job. The 1989 magnitude 6.9 Loma Prieta earthquake, while near the San Andreas fault, actually occurred on a neighboring sub-parallel strand, according to USGS research geologist Kate Scharer, a coauthor of the USGS study. Earthquakes of 1992 in Landers and 1999 in Hector Mine broke faults at the surface, but didn’t do it at the main plate boundary, Biasi said.

Only sections of the San Andreas, San Jacinto and Hayward faults that have 1,000 years’ worth of data on earthquakes were included in the analysis because the authors needed that data to look for periods of seismic activity and inactivity. Although the 1968 Borrego Mountain and other earthquakes at the extreme southern edge of the San Jacinto fault system have broken ground, those sections of the fault are not included in the study; there are no records available to determine if those areas produced many earthquakes over the last millennium, and as a result, are among California’s most worrisome.

There have been more mild seismic storms in recent memory.

The earthquake storm in the ’80s and ’90s is clearer in hindsight, said Caltech seismologist Egill Hauksson. It began with the Whittier Narrows temblor in 1987 (magnitude 5.9), which killed 8; followed by Pasadena in 1988 (4.9); Montebello in 1989 (4.4); Upland in 1990 (5.2); Sierra Madre in 1991 (5.8), which killed a woman; before ending with Northridge in 1994, which resulted in the deaths of at least 57 people.

More severe periods of earthquake activity were seen in the 19th century. Mission San Juan Capistrano endured shaking and suffered damage from two earthquakes — both greater than magnitude 7 — within a span of just a dozen years.

The first came in 1800 from a quake on the San Jacinto fault east of Temecula. Then, in 1812, movement of the San Andreas and San Jacinto faults through present-day cities like San Bernardino, Rialto, Loma Linda, Yucaipa and Highland brought down the mission’s Great Stone Church, killing more than 40 people inside.

“The Inland Empire would be strongly impacted” if those quakes repeated today, Scharer said.

There are other examples of frequent major earthquakes. In the 1500s, for instance, three major San Andreas fault earthquakes hit along the Grapevine, according to Scharer, possibly all within 30 years. And over the last 1,000 years in the southernmost 100 miles of the San Andreas fault system, there have been three periods of increased seismic activity — between 900 and 1100, 1200 and 1400, and 1600 to 1800, according to Rockwell. In that section, it has been relatively quiet for the last 219 years.

“If this pattern continues, we could well start a new phase of activity,” Rockwell said.

Turkey shows how a region can be affected by an above-average rate of earthquakes that persists for generations. A 1939 earthquake was the start of a series of 11 large temblors on the North Anatolian fault lasting at least 60 years, generally moving westward toward Istanbul, according to Stein, chief executive of Temblor.net and a former USGS geophysicist who has written extensively on the Turkish quakes.

Sometimes there was a 30-year gap between big quakes; sometimes, only one.

The most recent catastrophic earthquake was a magnitude 7.4 that caused more than 17,000 deaths. The 1999 temblor struck the industrial heartland and densely populated areas. And there’s concern Istanbul is next.

“Istanbul has been kind of on tenterhooks ever since the 1999 Izmit earthquake. They have an early warning system. They’ve done billions of dollars of infrastructure upgrades … a good job, considering it’s a very old city with lots of frail buildings,” Stein said.

While Istanbul might be on alarm for a future big one, many Californians are out of practice.

The last time California has seen an earthquake as powerful as a magnitude 7.8 was in 1857 in Southern California and 1906 for Northern California. No one alive today has first-hand experience with that kind of quake in the Golden State.

For instance, the magnitude 6.7 Northridge quake of 1994, which severely shook just a fraction of Los Angeles County, would pale in comparison with a magnitude 7.8 quake on the San Andreas. That would produce 45 times more shaking energy than the 1994 temblor, and a plausible scenario would not only send strong shaking to much of L.A. County, but also parts of five others: Kern, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and Ventura.

“If we had earthquakes as frequently as we had prior to 1906 within the last 50 years, people would be a lot more in tune with what earthquakes can do, and have a lot more interest in earthquake preparedness,” said Tim Dawson, senior engineering geologist at the California Geological Survey.

A sudden jump in how often earthquakes come can make recovery difficult.

New Zealand’s South Island has faced elevated seismic activity for 16 years — and it’s still not over, even after a magnitude 6.3 Christchurch earthquake of 2011 caused the deaths of 185 people and collapsed many buildings.

Four months after the Feb. 22, 2011, earthquake, a magnitude 6 hit southeast of Christchurch; then a 5.8 and a 5.9 on the same day half a year later. Valentine’s Day in 2016 brought a magnitude 5.7 quake. “It’s definitely on the high side of numbers of aftershocks,” said Matt Gerstenberger, principal seismologist for New Zealand’s seismic monitoring agency, GNS Science.

The constant shaking caused significant impact to people’s mental and social health. “Rates of things akin to PTSD started showing up amongst people,” said Sara McBride, a public information official for the region’s emergency management agencies between 2006 and 2011. “It’s a constant reminder of that which you have no control over.”

Experts say it’s important that Californians are psychologically prepared for the prospect of a new era of earthquakes.

That means not only having an emergency plan and supplies, said McBride, now a social scientist for the USGS’ earthquake early warning system, but mentally imagining what that will mean — not just putting a flashlight and shoes next to the bed, for instance, but understanding that will mean dealing with broken glass on the floor and a power outage that may last weeks or more, and planning for how your family will get through it.

“If we accept that there will come a time that the Earth is going to be more active than usual … that this is a natural process going on,” and plotting how you might react, McBride said, “that gives you a sense of psychological preparedness.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.