Hollister Ranch owners are fighting the state again over public’s right to use the beach

- Share via

West of Santa Barbara is a remnant of old California: Hollister Ranch. The 14,500 acres of hilly grassland, coastal sage scrub and secluded beaches look much like they did two centuries ago under Spanish control.

Red-tailed hawks circle. Migrating whales breach in the sparkling Pacific. Old oak trees dot the landscape, and a chain of reefs and scenic points produce perfectly shaped waves at such breaks as “Razor Blades,” “Little Drake’s” and “Lefts and Rights.”

The owners of Hollister Ranch property, including surfers, celebrities and successful professionals, cherish their exclusive domain and aggressively limit access. For decades, they have fought to keep the coastline almost entirely to themselves.

Now the landowners and ranch officials are back in court seeking to derail the latest move by the California Coastal Commission and State Coastal Conservancy to let non-residents onto beaches that are public by law as well as sections of privately owned shoreline.

The agencies want to take advantage of easements the YMCA offered the state in 1982 as a condition of the commission’s approval of a $2.7-million recreational center on land that eventually became part of Hollister Ranch.

If the state prevails, it would be a major victory for the commission and conservancy, which have tried for more than 35 years to give the public a way to use the coast along one of the last large holdings of property along California’s shore.

The offer, which was finally accepted by the state in April 2013 after years of controversy, would allow 50 people a day to reach stretches of surf and sand that have been off limits or unreachable except by boat or a difficult walk in from Gaviota State Park on the east or Jalama Beach County Park above Point Conception.

“We have to have access there,” said Linda Locklin, the Coastal Commission’s access manager. “The state Constitution grants the public the right to use the beach up to the mean high tide line. But exercising your constitutional right at the ranch has been difficult or virtually impossible.”

Attorneys for the Hollister Ranch Owners’ Assn., the Hollister Ranch Cooperative and property owners contend, however, that the proposed easements should be cancelled because the YMCA of Metropolitan Los Angeles never had the authority to grant them to the state.

Their main claim is that the YMCA did not get permission from the ranch association and property owners before offering easements involving land, a 3,880-foot length of beach and the ranch’s main road, none of which the Y owned.

It is further alleged that the easement offer was improperly recorded and two owners were not notified in a timely way about the proposed easements on their land.

“This lawsuit centers on fundamental property rights and whether or not your neighbor can grant the general public access to your property without your permission or even prior notification,” said Monte Ward, president of the Hollister Ranch Owners’ Assn. “The Coastal Commission is relying on a flawed agreement that could significantly impact private property owners and jeopardize decades of environmental stewardship.”

Hollister Ranch remains one of the last sections of sparsely developed California coastline. It contains 8.5 miles of pristine beaches, a 2.2-mile-long shoreline preserve and 136 parcels owned by hundreds of individuals, many of whom hold shares in the lots, which average about 100 acres.

Property owners have built about 75 structures including homes, stables and barns that often blend into the vast landscape. A fraction of a parcel without a house now sells for hundreds of thousands of dollars while lots with homes are worth millions.

Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez is traveling from Oregon to Mexico along 1100 miles of stunning California coastline. Join him and participate in his quest to #SaveYourCoast

Among the owners are Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard, singer-songwriter Jackson Browne and movie producer James Cameron, who operates a “bio-dynamic” farm complete with a helicopter pad.

The entire property has been a working cattle ranch since 1791 when it was part of the original Rancho Nuestra Señora del Refugio.

“It’s a special place,” said Steve Pezman, the publisher of Surfers Journal and a former editor of Surfer magazine who has been to the ranch. “There is something to be said for sharing the asset with others, but if sharing threatens the asset . . . If I were an owner, I’d probably be resentful.”

The clash over property rights and public access began almost 40 years ago when a group of landowners sued the Coastal Commission for requiring public easements as a condition of their development permits. They ended up paying an in-lieu fee of $5,000 that was created by the Legislature.

Exercising your constitutional right at the ranch has been difficult or virtually impossible.

— Linda Locklin, access manager, California Coastal Commission

Over the years, the owners have resisted an access plan developed by the Coastal Commission and Coastal Conservancy. The ranch association successfully sued in 1982 to halt the YMCA’s construction of its camp and conference center.

When the Clinton administration proposed turning 46 miles of coastline in northern Santa Barbara County into a national seashore, the ranch association raised $300,000 to hire a lobbyist to oppose the idea. The association, along with other property owners in the region, also sued repeatedly to stop a federal study of the proposal, but to no avail.

In 1999 and 2012, the ranch owners asked the Coastal Commission to rescind the YMCA’s easement offer. The requests were denied.

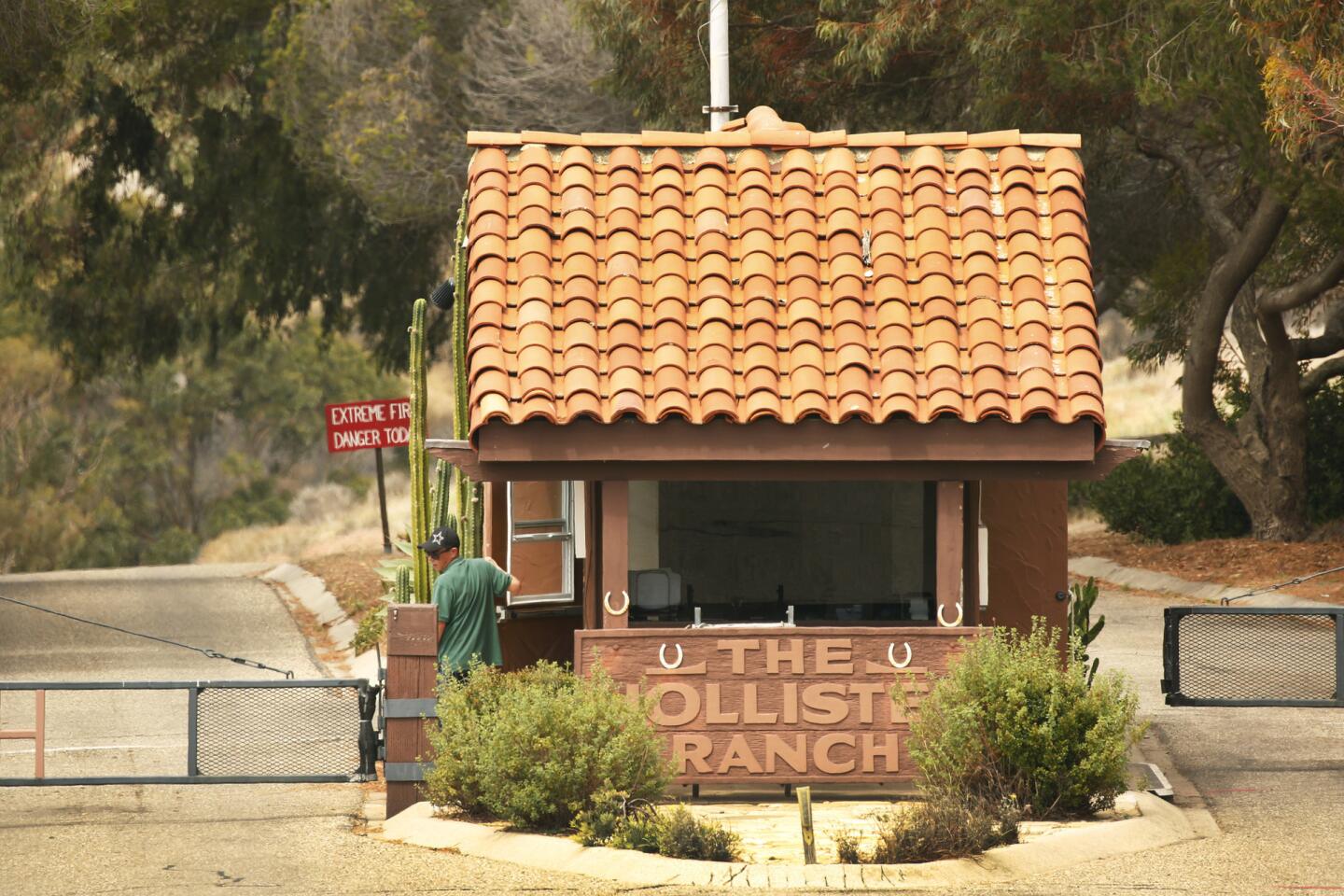

The ranch keeps the public at bay with a guard shack, gates and security patrols. Some owners also have resorted to intimidation and harassment, even when outsiders were in state waters or on the public portion of beach below the mean high tide line, according to owners and government reports.

A few ranch residents have even confronted fellow residents for bringing in what they considered too many guests. And, according to Coastal Commission records, people who were invited in have been hassled by security guards.

Surfers in particular covet access to that stretch of coast and have reported people associated with the ranch threatening them with guns.

Many surfers launch small power boats or inflatable dinghies from nearby Gaviota State Park to reach the ranch’s breaks. Before the pier closed in 2014 due to storm damage, the hoist used to lower surfboard-laden craft into the water was sabotaged repeatedly.

One veteran surfer, who spoke on the condition that his name not be used, said he motors by Hollister Ranch in his power boat and goes to several prime surf spots closer to Point Conception.

“You could get physically threatened, dropped in on or accosted verbally by the locals,” he said. “I’m sympathetic to the owners’ situation, but I am also proud of the state and the Coastal Commission for their dedication to getting public access to the beach.”

This is one of the most interesting and important public access cases in California.

— Attorney Mark Massara

The property owners contend, however, that letting the public in could spoil the ranch’s coastline and undo years of effort to protect the environment.

They point out that Hollister Ranch already grants temporary access to scientists, academics, historical societies, environmental groups and schoolchildren.

Steven A. Amerikaner, a former Santa Barbara city attorney who represents the ranch association, said there is tension in the California Coastal Act between preservation of natural resources and public access as well as a recognition that access can be detrimental to the preservation goal.

“Hollister Ranch is not near population centers,” Amerikaner added. “There is a good argument that the preservation goal ought to get primacy here and public access should be pursued closer to the populated areas of the state.”

In the latest access fight, ranch organizations and owners sued the Coastal Commission and Coastal Conservancy in Santa Barbara County Superior Court in May 2013. The lawsuit was filed a month after the conservancy formally accepted the YMCA’s easement offer and recorded it just before the deadline lapsed.

Last week, both sides went before Judge Colleen K. Sterne. In a tentative ruling, she rejected their arguments to decide the case, which could clear the way for trial.

Sterne’s final decision is pending. Another hearing to discuss the status of the case is set for Aug. 22.

“This is one of the most interesting and important public access cases in California from a legal perspective and for anyone interested in the history of coastal access. There’s a riveting set of facts, but we are a long way from knowing the outcome,” said Mark Massara, an environmental attorney and former manager of the Sierra Club’s coastal program.

Supervising Deputy Atty. Gen. Jamee Jordan Patterson, who represents the state agencies, contends the YMCA was under no obligation to obtain permission from property owners because the easement offer is an “irrevocable license” for public access.

In her court filings, Patterson argues that the YMCA acquired its land and easements in 1970, a year before Hollister Ranch was created and subdivided and before the Hollister Ranch Owners’ Assn. and other landowners had property rights there.

The ranch association, which sued the YMCA to stop construction of the camp, obtained the Y’s property and easements in 1983 as the result of a settlement of the lawsuit.

Patterson further argues that the YMCA easements permanently apply because the organization began construction as allowed by the Coastal Commission’s development permit, including wooden piers for a foundation and installation of a water tank.

If the commission and conservancy don’t prevail, Locklin said, neither agency is likely to give up trying to open up the Hollister Ranch beaches — a goal that was added to the Coastal Act in 1982.

“We would see what our future options are,” she said. “The YMCA chapter would be closed, but we still have our access plan, and the local coastal program for Santa Barbara County calls for public access.”

Twitter: @LADeadline16

ALSO

Bill to ban private communications by California’s coastal commissioners gets sidetracked

Why California’s northern coast doesn’t look like Atlantic City

Steve Lopez: This TV producer and coastal commissioner thinks the columnist is a conspiracy theorist

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.