L.A. officials ask LAPD to find ways to put more officers on city streets

- Share via

Los Angeles lawmakers pressed the Police Department on Tuesday for detailed reports explaining how officers are deployed across city streets, echoing simmering concerns that there aren’t enough cops working patrol duties to adequately respond to calls for help.

The scrutiny comes as crime in Los Angeles continued to rise last year and amid complaints from residents and officers about slow response times and a diminished police presence in some neighborhoods.

The hour-plus discussion at a meeting of the City Council’s Public Safety Committee — where LAPD brass filled two front rows — marked the latest round in the ongoing debate over how many officers should patrol city streets. Although the five-person committee did not take a vote Tuesday, the motion that prompted the conversation calls for the LAPD to establish “more realistic and robust” patrol staffing levels.

Council members expressed frustration throughout the hearing, describing decades-old reports critiquing the LAPD’s deployment strategies.

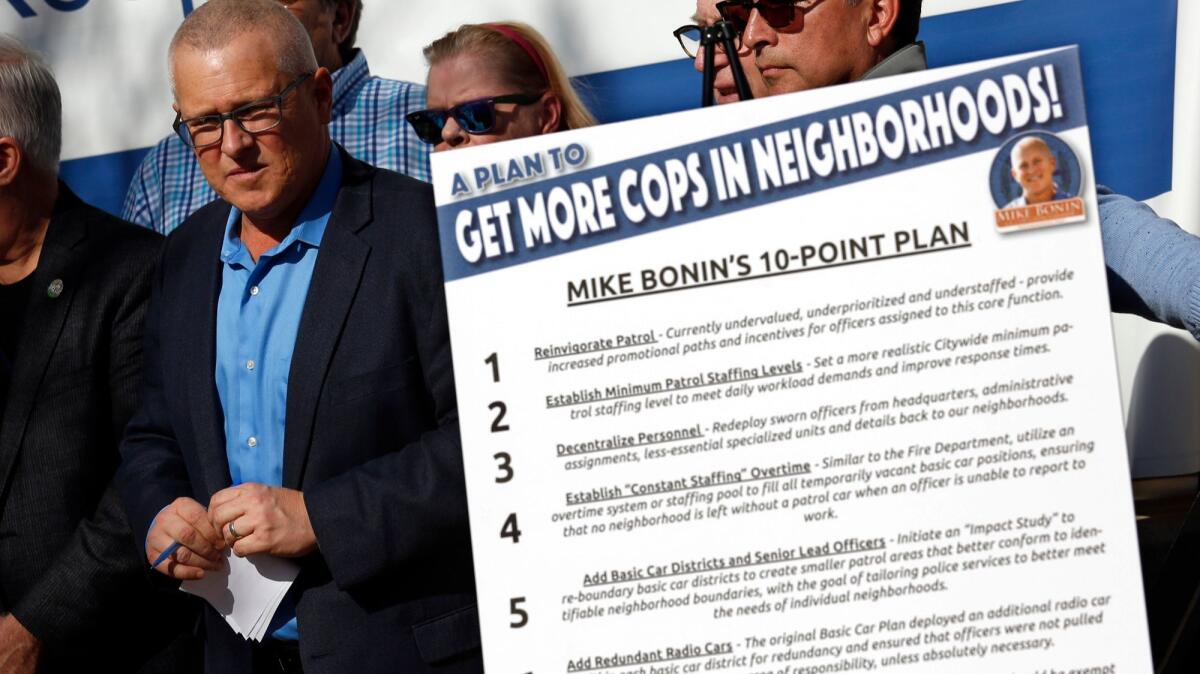

“This has been an issue that has been festering for a very long time,” said Councilman Mike Bonin, who introduced the motion along with Joe Buscaino. “The time has come, after 30 years of reports and blue-ribbon commissions and council motions, to get serious about this.”

How the LAPD uses its roughly 9,900 officers has drawn fresh attention from City Hall in recent months, with the union representing rank-and-file cops leading the charge. Union officials have accused LAPD brass of pulling too many officers from patrol duties for specialized units, such as the recently formed Community Relationship Division and much-publicized Metropolitan Division, an elite unit that was doubled in size in 2015 to help suppress the citywide crime surge.

As a result, the police union has said, patrol officers are forced to rush from call to call, slowing response times, preventing police from building connections with residents and hurting officer morale.

“Our rank-and-file officers are feeling incredibly frustrated,” said Robert Harris, one of the union’s directors. “They want to be able to handle the call load that they are given and to be there for the citizens when they need them. But they are unable to do that.”

Those supporting the call for more patrol officers have pointed to a figure from 1969, which was cited in the motion introduced by Bonin and Buscaino. On an average day in 1969, they said, 337 cops patrolled the city in about 180 cars. By comparison, during one afternoon in December 2016, 311 officers patrolled the city in fewer than 160 cars, according to the motion.

LAPD Assistant Chief Michel Moore cautioned council members that the department’s current deployment strategy reflected the “added complexity” of law enforcement in 2017. Today, he said, specialized units — those that address domestic violence, gang crime, mental illness and homelessness, for example — “augment and support” the cops working patrol duties.

For example, in addition to the 311 officers on patrol on the December afternoon, an additional 462 personnel were working special traffic, gang, mental health or Metro details, according to a handout from the LAPD.

“The LAPD of 2017 is vastly different from the LAPD of 1969,” Moore said. “It’s a department that focuses on long-term problem-solving rather than merely responding to emergency calls and arresting people.”

LAPD brass and the police union have found common ground on some issues raised during the debate over deployment. Both have urged city officials to hire more civilians to perform some of the jobs currently filled by sworn officers. They also agree that the city needs to hire more police officers — Chief Charlie Beck pegged the number at 2,500 additional cops at a Public Safety Committee meeting last year.

But hiring police officers is an expensive and time-consuming process, and growing a department’s ranks long-term is a process hampered by officers who retire or otherwise leave the force.

At the end of Tuesday’s meeting, as the committee instructed the LAPD to provide a deeper analysis of deployment strategies and potential changes, some council members acknowledged their frustration over having a similar conversation a year ago.

At that 2016 meeting, committee members grilled the LAPD over the city’s persistent uptick in crime and questioned whether the department had adequately allocated its resources in response. Little came from that hearing, Councilwoman Nury Martinez noted.

“Having this annual conversation about the rise in crime and what are you doing with your numbers, where are you putting people, why aren’t we seeing black-and-whites in our neighborhoods — for me, it’s actually becoming a little bit ridiculous because we’ve had this conversation,” she said. “I just don’t know what we’re doing about it.”

For more LAPD news, follow me on Twitter: @katemather

UPDATES:

12:10 a.m., Feb. 22: This article was updated with information about crime in Los Angeles.

This article was originally published at 7:10 p.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.