A ‘fort’ built by accused Lunada Bay surf bullies has been demolished — will it end their localism?

- Share via

At least some spectators gazing from the bluffs of Palos Verdes Estates hoped the metallic rap of jackhammers rising from Lunada Bay this week sounded the end of an era.

For decades, outsiders have complained that they were harassed and their vehicles vandalized by a crew of surfers determined to keep the bay’s well-shaped waves to themselves.

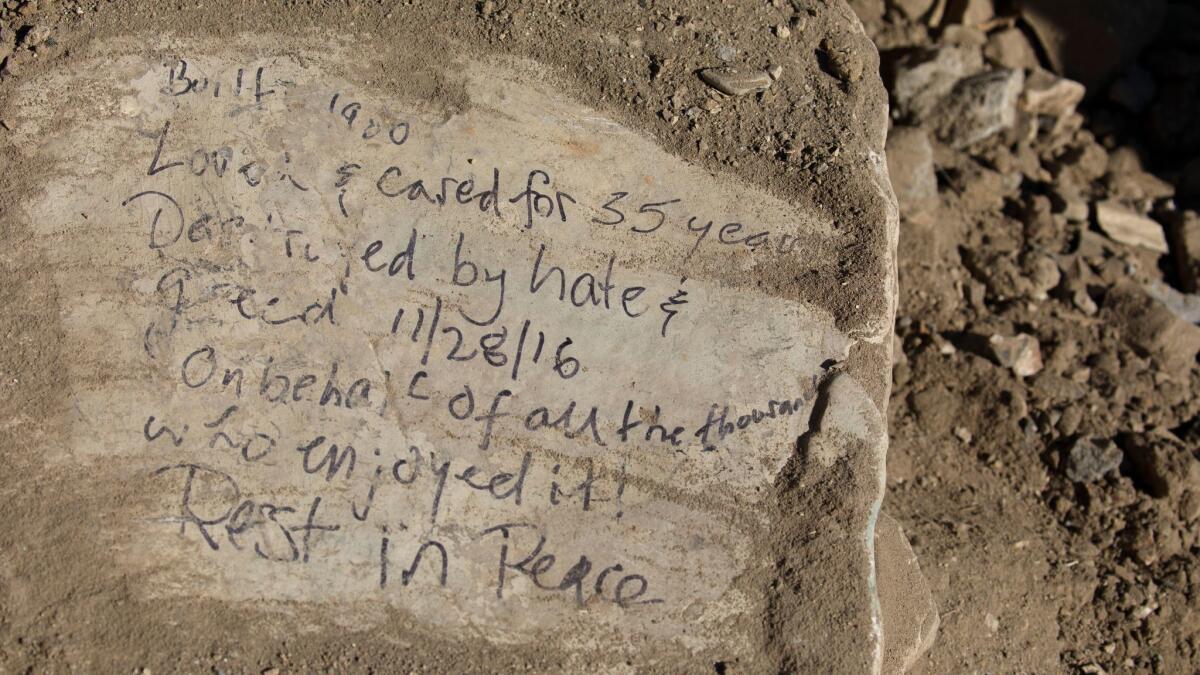

On Thursday, after months of pressure on the city by the California Coastal Commission, a wrecking crew finished dismantling the stone “fort” the surfers, dubbed by some as the Bay Boys, had built without permits on the rocky shore.

“This is great,” said a veteran surfer from Redondo Beach, who did not want to be identified out of fear of reprisal. “I’ve had rocks thrown at me and been intimidated twice … I never surfed the bay because of it.”

But if tearing down the fort was meant as a sign that authorities have finally lost patience with the bullying known as localism, that was diminished by the fact that someone sneaked in one night and damaged workers’ trucks and set fire to their air compressor.

Palos Verdes Estates officials, whom many have criticized for failing to take effective action against the territorial surfers, are investigating the vandalism. They said that tearing down the structure that served as a sort of clubhouse for the surfers is just one step in addressing the hostility toward outsiders.

Critics say the action comes only after the Coastal Commission intervened and told the city to increase public access to the beach.

It also coincides with two lawsuits accusing the surfers of bombarding outsiders with rocks, slashing their tires and assaulting them in the water or along the treacherous paths that lead down to the beach. The cases also accuse the city of failing to do what’s necessary to stop the intimidation.

“We are making progress toward resolving a problem,” City Manager Anton Dahlerbruch said. “We are confident that the measures we are taking will positively improve the public’s enjoyment of the bay.”

He said the city has increased police patrols and plans to monitor surf reports during the winter wave season and assign more officers as needed. If a proposed contract is approved with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, deputies will monitor the bay when local authorities are unavailable, Dahlerbruch said.

Localism, a territorial practice to exclude outsiders, has probably been a part of surfing since the first time two people tried to catch the same wave. As Southern California’s population grew, so did the aggression of surfers at some notorious breaks, such as Windansea in San Diego and Hollywood by the Sea in Oxnard.

Paradoxically, though, crowding on waves eventually made localism moot, said Scott Hulet, the editor of Surfer’s Journal.

“This sort of thing has been absorbed by extreme numbers in the water,” he said. “It’s a real anachronism to be in the heart of Los Angeles and have a group assume any sort of ownership over a surf spot.”

But Lunada Bay, which has long had a reputation for the worst localism on the coast, is still seen by many as a dangerous place where well-to-do bullies with a sense of entitlement use threats and violence to lord over a slice of coast as if it were theirs alone.

“There is no place like Lunada Bay,” said Steve Hawk, a former editor of Surfer magazine who was confronted himself by a group of locals at the top of the bluff after surfing the break.

“This is not private land or a private beach,” he said. “The public has a right to be there. Imagine if a bunch of African Americans from South-Central Los Angeles did something like this at Lunada Bay. How would the city of Palos Verdes Estates react? The city has given [the Bay Boys] a pass for decades.”

The Coastal Commission, which eventually stepped in to make sure the public can get to the public beach, has been in discussions with city officials off and on since January.

Though the powerful land use agency supports the increased police patrols, its correspondence with the city shows continuing concern that Palos Verdes Estates has not implemented the commission’s recommendations to enhance access by improving trails to the beach and adding benches, signs and viewing areas on the bluffs.

“We identified the fort as a potential site that could be used to intimidate beach-goers,” said Andrew Willis, a commission enforcement supervisor. “We will monitor the situation. Restricting access to the beach is a Coastal Act issue.”

In a letter sent to the commission in October, Dahlerbruch, the city manager, said the city opposes the recommendations because it wants to maintain its coastal bluffs and beaches in a pristine natural state. He added that the stepped-up police presence has been effective — as demonstrated by a lack of significant incidents.

But two pending lawsuits in federal and state courts challenge the city’s commitment to solving the problem. The suits, which name Palos Verdes Estates, Police Chief Jeff Kepley and 10 individuals as defendants, allege that the intimidation of outsiders has persisted for years despite city efforts.

El Segundo Police Officer Cory Spencer, Diana Milena Reed and the Coastal Protection Rangers Inc., a small nonprofit organization, brought the cases earlier this year.

Spencer said he was harassed repeatedly and run over in the water by a surfer in late January during his first visit to the bay.

“This is not about money,” he said. “It’s about changing the behavior out there and giving part of the coast back to the public.”

Named as defendants are David Melo, Mark Griep, Sang Lee, Brant Blakeman, Michael Rae Papayans, Angelo Ferrara, Frank Ferrara and Charlie Ferrara and one minor. At this time, Alan Johnston is a defendant only in the the federal case.

The lawsuits, which claim the Bay Boys amount to a street gang, specifically mention 12 alleged incidents in which beach-goers, including the organizer of a surfing event to honor the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., were harassed, assaulted, threatened and intimidated.

Victor Otten, one of the attorneys representing Spencer and Reed, has a profanity-laced video of Bay Boys intimidating beach-goers, more than 100 statements from witnesses and 57 police reports filed over the last 20 years related to harassment, assaults and vandalism involving Lunada Bay surfers.

Attorneys for the city and Chief Kepley deny the allegations, but they said it is too early in the litigation to provide any specifics of their defense. Two other lawyers representing Johnston and Blakeman questioned whether the so-called Bay Boys amounted to a criminal street gang and contended that the situation at Lunada Bay has been greatly exaggerated.

“There is the allegation of a criminal street gang. This is legally incorrect and truly disrespectful of the victims of actual street gangs,” said J. Patrick Carey, Johnston’s attorney, who described the defendants as friends and members of a surfing club.

Carey contended that the one allegation against his client, for battery, is groundless.

“The concept of the Bay Boys is a false one,” said Robert S. Cooper, Blakeman’s attorney. “As to Mr. Blakeman, he has lived here [in Palos Verdes Estates] almost his entire life. He is loved and respected. He has very strong support in the community. ...He has never done . . . anything that is alleged in the lawsuit.”

Those who say they are out to end localism at Lunada Bay contend that the destroying the fort was an important step.

Police reports over the years show that the shelter, with its stone patio, fire pit, table, wooden benches and palm thatch roofing, was constructed without permits near the water’s edge, and was the site of parties as well as frequent drug and alcohol use.

Otten, one of the attorneys behind the lawsuit, has emails from a witness to Palos Verdes Estates police indicating that officers have been present at the shelter while people were drinking alcohol but did nothing about the municipal code violation.

Some who watched the shelter’s demolition this week doubted that the action will have the desired effect and questioned whether the news media and others have exaggerated the situation.

“I don’t understand what razing that patio is going to do to stop territoriality,” said Earl Isaacson, 68, who lives in the Lunada Bay area and has attended barbecues at the shelter. “I have been here 35 years, and I have never witnessed anyone getting hassled. They are tying to make it look like these guys are a gang. It’s not a gang. There are lots of people here with good jobs. It’s all been blown out of proportion. No one up here wanted that patio torn down. It’s like a landmark.”

ALSO

Allegations flowing in against the surfer gang of Lunada Bay

Beach fort erected by ‘Bay Boys’ surfer gang will be demolished, Palos Verdes Estates officials say

Contractors’ equipment vandalized during demolition of surfers’ stone ‘fort’ at Lunada Bay

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.