County issued conflicting evacuation warnings before deadly Montecito mudslides

- Share via

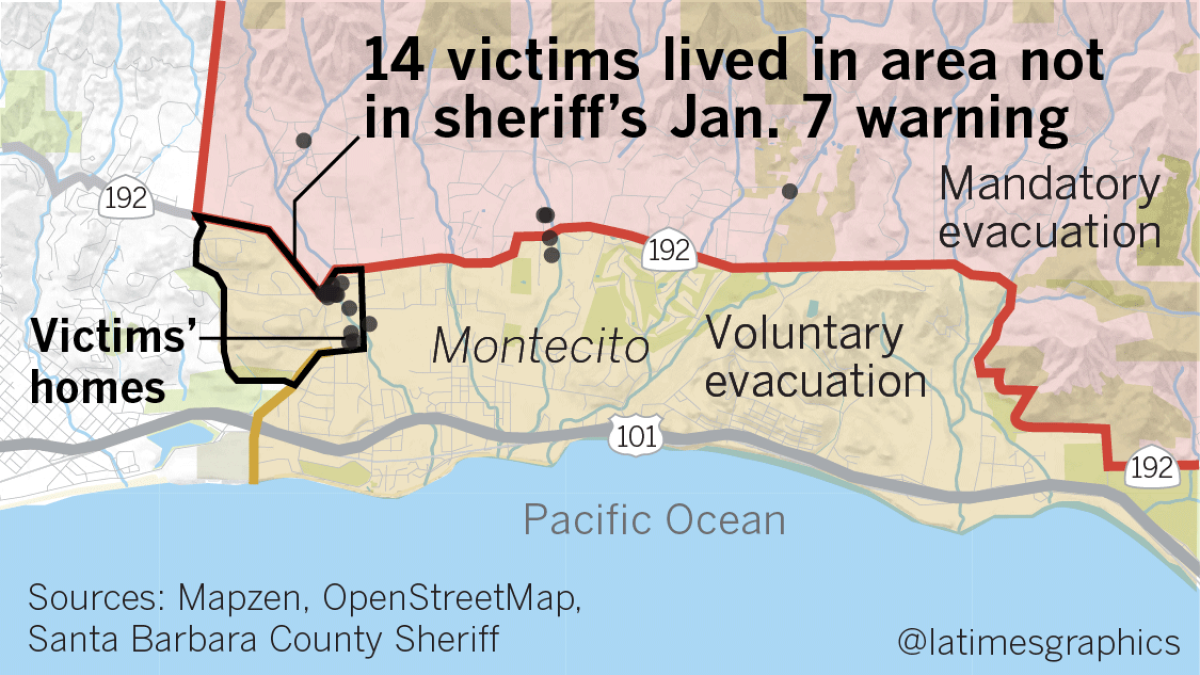

In the days before deadly mudslides devastated Montecito, Santa Barbara County officials released conflicting evacuation instructions that left some hard-hit neighborhoods out of the warning zone.

The Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office posted a list of voluntary and mandatory evacuation areas for the town on Facebook and linked to the list from its website. But a separate map on the county’s main website included a larger voluntary evacuation zone that included dozens of homes not covered by the sheriff’s list.

For the record:

8:00 a.m. Jan. 24, 2018An earlier version of this story said that the Sheriff’s Department posted incomplete information about evacuations on Facebook and on its website. That information did appear on the department’s Facebook page and was accessible by hyperlink from its website. However, an evacuation list was not directly posted on its website.

Of the 21 people killed in the mudslide, at least a dozen lived in areas that were covered by the county’s evacuation map but not included in the Sheriff’s Office warnings, according to records and data reviewed by The Times.

In response to questions from The Times, Santa Barbara County emergency officials acknowledged the discrepancy while emphasizing the many other measures officials took to warn residents of an approaching storm that caused the mudslides, including emails, social media alerts, press releases and even deputies going door to door in some areas.

“Regrettably, however, also 30 hours prior to the storm’s arrival, I approved a press release and Facebook post that had discrepancies with the western boundary of our intended voluntary evacuation area,” Robert Lewin, San Barbara County’s director of the Office of Emergency Management, said in a statement.

Officials emphasized that all those who died were in a voluntary or mandatory evacuation zone and that the warnings probably saved more lives in what were the worst mudslides to hit California in several decades.

It remains far from clear whether a broader evacuation warning would have made a difference. Officials estimated that only 15% of the residents in the mandatory evacuation zone left the area.

But the discrepancy in the warnings adds to questions about whether more could have been done to get people out of harm’s way before the mudslides swallowed homes and buried residents. The Times reported earlier that the county did not send out Amber Alert-style bulletins to cellphones until the mudslides had begun. By then, it was too late for residents to flee. There were also technical snafus that prevented earlier warnings from getting to residents.

County officials said it’s important to now learn from the mudslides — as well as the fires that swept through the area weeks earlier — to improve evacuation preparations and warnings.

“If you’re not learning from every disaster and figuring out what to do better, than in my view you’re not doing your job,” said County Supervisor Das Williams, who represents Montecito and Carpinteria, in an interview last week. “Obviously in retrospect it would’ve helped to have more evacuated. But I don’t think there was any disagreement.”

Evacuation zone

The county had been warning for days of the coming rains and the mudslide risk. But there has been much debate about the actual evacuation orders.

At a news conference in Carpinteria on Jan. 5, Williams and others officials stood in front of a map that outlined what was possible in a 100- or 500-year storm for the county’s beach enclaves.

In Montecito, the map showed that the areas that would be hit hardest ran parallel to creeks that emerged from the foothill canyons and wounds south to the ocean. The hardest hit areas would be south of California 192 as mud and debris became lodged under bridges and in catch basins, eventually pushing the mud into residential streets.

In the end, that’s exactly what happened the morning of Jan. 9.

Authorities followed boundaries of evacuation zones similar to ones that had been established weeks earlier for the Thomas fire, where homes north of Highway 192 were deemed most at risk. Homes below the highway were considered to be in voluntary evacuation areas and less vulnerable to a landslide.

Sheriff Bill Brown, who ultimately makes the decision on the evacuation plan, said he approved the zones at the recommendation of local and county firefighters, emergency planners and experts from the U.S. Geological Survey, among others.

In the end, the rain was worse than expected, and the mud caused destruction much farther south than the initial estimates.

“The storm that was predicted, the storm that we prepared for, was not the storm that we received,” Brown said. “We knew that it was going to be bad. But looking at years gone by and where damaged occurred … the destruction was not anything close to the magnitude of this.”

Ahead of the storm, Williams said many of his constituents were doubtful that the runoff would live up the hype. At the Jan. 5 news conference, Williams said that the storm posed a “very clear and present danger” to vulnerable areas.

“The night of the storm I was monitoring Facebook and the tone I got from the community was, ‘If the storm doesn’t materialize, heads are gonna roll,’” he said. “We’re ready to hold people accountable for getting people all excited.”

It was a skepticism that sheriff’s deputies witnessed first-hand. One resident wrote on social media that it took a 20-minute conversation with officials before they ultimately decided to leave their home for the night.

“I’ve seen experts opine about how you essentially not only have to warn people but you sort of have to convince people,” Brown said. “That’s a difficult order, but one we’re obviously going to have to take a look at.”

But there isn’t a lot of science available on what message will truly make people appreciate a danger they cannot see, said Art Botterell, senior emergency services coordinator with the governor’s office.

“I’m afraid what makes them resonate is bitter experience,” he said. “If people haven’t experienced a hazard recently, they tend not to personalize it.”

Warnings need to be repeated and reinforced with other indicators, he said. If a resident sees a warning about a landslide from the National Weather Service and looks outside and only sees drizzling rain, they won’t be convinced, Botterell said.

But if other neighbors are leaving, they might take it more seriously. Or if a message from the weather service is followed up by a text alert from the county, then a broadcast on TV, radio or social media, the chances of people heeding the warning increases, he said.

“It’s just like advertising — repeated impressions make a difference,” Botterell said.

The danger of debris flows or floods are particularly challenging because they’re stealthy, according to experts. In most cases, people can see a fire raging over a hillside and smell it from miles away.

A landslide moves in with a whisper.

“People are going to evacuate when there’s a cop on every corner. They’ll stay out when there’s National Guard on every street,” said James Langhorne, who was the fire marshal for the Montecito Fire Protection District for 23 years before retiring nine years ago. “The real issue is that people have to own a piece of this thing. It’s not something you can do for them.”

Getting word out

County officials are eager to say their best option for messaging is their Aware and Prepare community alert initiative, a set of subscriber-based warning systems that can send timely texts, phone calls, tweets and emails to its users when a disaster is imminent or unfolding in real time.

But there are clear flaws in systems like these, said Botterell.

For one, visitors in a tourist-reliant community like Montecito don’t receive the messages because they haven’t signed up. Service workers who live on their employer’s property could also miss out.

Records show that Santa Barbara County relied almost exclusively on its Aware and Prepare initiative to distribute information to subscribers ahead of, during and after the storm, along with social media postings and traditional news media. Officials told The Times on Friday that about 50,000 people, or barely more than 10% of the county, is enrolled in the program. Thousands of additional landline calls were made through reverse 911.

It wasn’t until the storm was at its peak and homes were being washed away that the County Office of Emergency Management used a federal warning system to send a message to all cellphones in the affected area that they should take action, regardless of subscription.

Currently the system only allows agencies to send out 90-character texts to phones — not enough to give accurate details on the nature and location of a threat. That will change in May 2019 when the character limit jumps to 360, Botterell said.

But there needs to be a physical warning infrastructure in place too, Brown suggested, something along the lines of sirens, “because it doesn’t matter how many messages you send out if you don’t have your phone or if they’re not at their computer.”

Times staff writers Jon Schleuss and Alene Tchekmedyian contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.