Trump pledged to end the HIV epidemic. San Francisco could get there first

San Francisco has a plan to reduce HIV transmission and HIV-related deaths by 90 percent by 2020.

- Share via

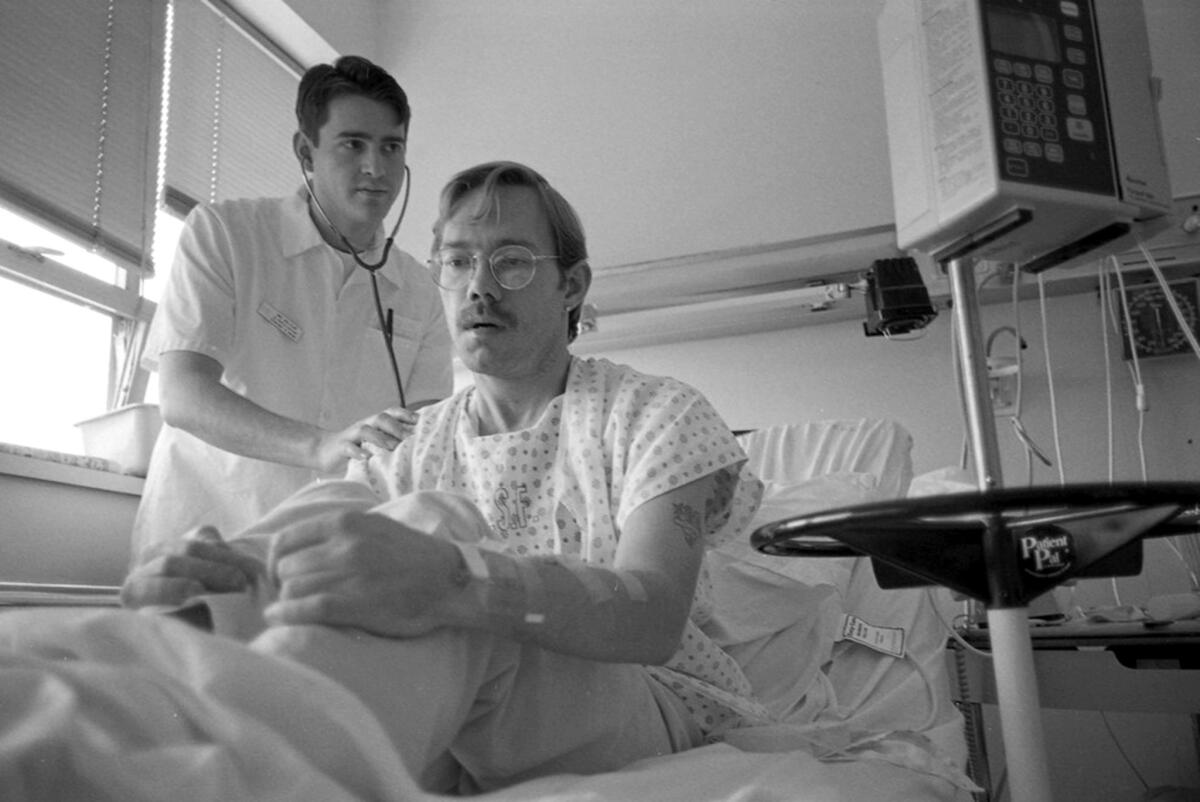

In a different city, in a different decade, the news would have changed David’s life forever.

Instead the graduate student, who dreams of someday acting and teaching, told himself one thing as he waited for test results in the San Francisco General Hospital emergency room: “If it comes back and it’s positive, just do what you can to stay healthy.... If it comes back negative, be even more careful.”

David’s HIV test was positive.

Two days later, he met with a social worker in Ward 86 — the first dedicated HIV clinic in the U.S., founded in 1983. He got help, that same day, to sign up for insurance he can afford. He got a starter pack, that same day, of antiretroviral therapy and a prescription for more.

When his pharmacist told him there would be a $1,195 copay, his social worker made the copay go away. David, who is 33 and asked that his last name not be used, takes two tablets each day: Descovy, a sky blue rectangle with rounded corners, and Tivicay, a small circle of corn-silk yellow.

After two weeks, the virus was undetectable in David’s blood. As long as he stays on medication, HIV will not determine his future. Just as important, he will not transmit the disease to anyone else.

David’s success is San Francisco’s success. This city is on course to be the first in the country to eliminate new HIV infections — or at least come close. President Trump pledged in his State of the Union speech that the U.S. will “eliminate the HIV epidemic … within 10 years.” San Francisco is poised to get there first.

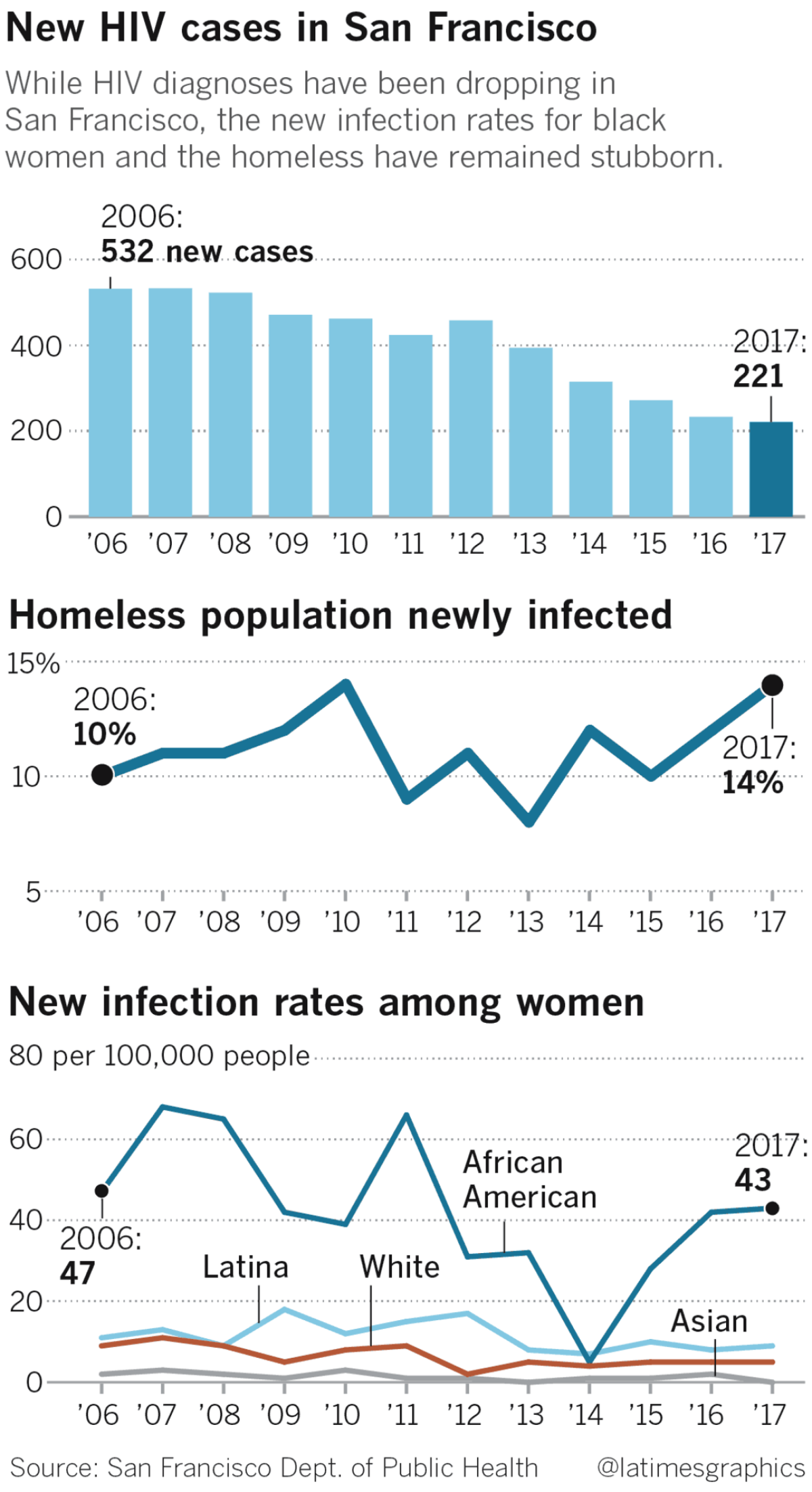

More than 2,300 new, full-blown AIDS cases were diagnosed here in 1992, the peak of the epidemic. In 2017, the most recent official statistics available, 221 people were diagnosed with HIV, the virus that can lead to AIDS. When the 2018 statistics are released in September, that number is expected to drop to around 190.

“San Francisco is a model for the rest of the nation,” said David C. Harvey, executive director of the National Coalition of STD Directors. “Some states and cities … do not have the resources of San Francisco and will have a problem replicating the exact model. But places like San Francisco, New York City and Seattle — with San Francisco leading the pack — are important jurisdictions at showing the rest of the country what is possible.”

The immediate goal of the city’s ambitious Getting to Zero campaign is to reduce new HIV diagnoses by 90% between 2013, when there were 394 cases, and 2020. San Francisco is only about halfway there but is moving faster than the nation as a whole and any other big city.

“San Francisco is a model for the rest of the nation.”

— David C. Harvey, executive director of the National Coalition of STD Directors

The first step in its three-pronged approach is rapid testing and antiretroviral therapy to keep people healthy and stop the spread of infection. Next is the widespread prescription of PrEP, a.k.a. pre-exposure prophylaxis, a pill that keeps healthy people from getting infected. And finally, a network of outreach workers find people who have stopped regular HIV testing and work to get them back into care.

The city’s greatest success has been in reducing the rate of infection among gay men. And the biggest challenges? Reaching African American men, whose infection rate is the highest, and making sure infected homeless people receive the medical care they need. That effort was strengthened last week with the announcement of San Francisco’s first POP-UP clinic, under the direction of Dr. Monica Gandhi, medical director of Ward 86; the “UP” stands for Unstably Housed People.

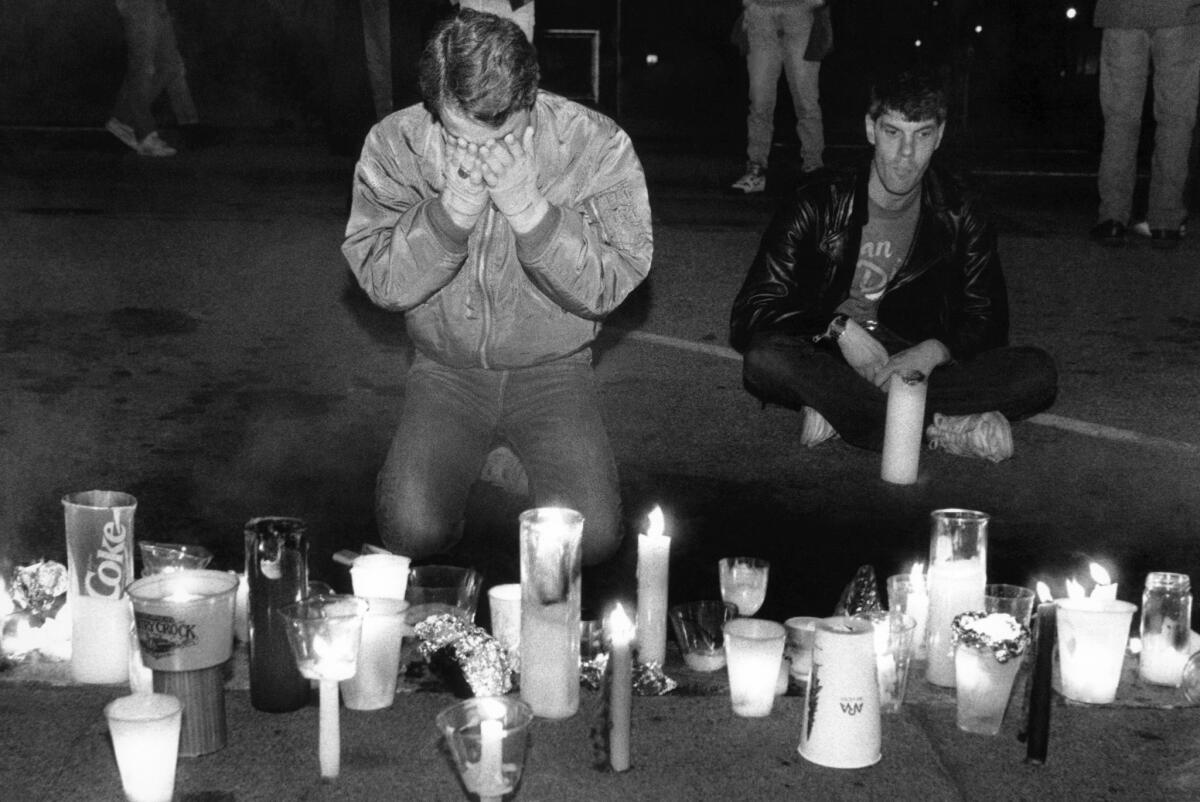

Trump’s State of the Union address devoted just 81 words to the subject of HIV. But his pledge to eradicate the disease resonated here in the city where AIDS mowed down so many young lives and galvanized generations of scientists, doctors and activists.

Dr. Diane Havlir, a co-founder of Getting to Zero, was a young medical resident here during the epidemic’s darkest days.

The AIDS patients she saw were her age, she said, “and they were sick and they were dying and some were blind and some had purple spots all over their bodies and we knew about some of the infections, but we had no treatment. And once we started getting treatment, the treatment was very, very rough on the patients.”

Havlir, who is a professor at UC San Francisco and head of the HIV program at San Francisco General, was heartened by Trump’s pledge, which she said “broke the silence” this administration has had about HIV. But pledges alone aren’t sufficient, she said. “We need science. We need community involvement. We need funding.”

Trump’s 2020 budget asks for $291 million for the effort in its first year. But it also proposed cuts to Medicaid and other programs that are central to the fight against HIV. The result, said the Act Now: End AIDS Coalition, is a federal budget that “fundamentally undermines the ambitions” laid out by the administration.

However, Harvey noted, the administration has since said it will reallocate some funding to its HIV eradication effort in the 2019 fiscal year. “This is good news,” he said.

David, who is working toward his master of fine arts degree, received care through the Rapid ART Program Initiative for HIV Diagnoses. Its goal is to make sure people who test positive are offered antiretroviral therapy within five days of diagnosis.

RAPID has had significant effects. Between 2013 and 2016, the percentage of patients linked to care within one month of being diagnosed with HIV has jumped from 72% to 83%. The median number of days between starting medical care for the infection and receiving antiretroviral therapy dropped from 27 days to zero, according to the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

And then there is PrEP.

“I never had a gay reality without HIV, and now I’m immune.”

— Rand Hunt, activist in San Francisco’s leather culture

When Rand Hunt talks about the pre-exposure medication, he sounds as if he has just witnessed a miracle.

He was born in 1984, the year HIV was identified as the cause of AIDS, and has lived his entire life in the shadow of the epidemic. He is a web designer, an activist in San Francisco’s leather culture and HIV-negative. He does not foresee his status changing.

All because of a small blue pill, brand name Truvada. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that when it is taken consistently “it has been shown to reduce the risk of HIV infection in people who are at high risk by up to 92%.” When used with a condom, it is even more effective.

“I never had a gay reality without HIV, and now I’m immune,” Hunt said. “The awareness is like the dawn, the sun coming up, the plague being over.… For me, it means that I can be present when I have sex instead of being, like, ‘The condom’s gonna break and I’m gonna die.’”

Dr. Susan Buchbinder, who directs the health department’s Bridge HIV program and co-founded Getting to Zero, said the city has gone from an estimated 4,400 people on the drug in 2014 to between 16,000 and 20,000 people today.

Among the largest providers is Magnet, a men’s sexual health clinic in the Castro District run by the nonprofit San Francisco AIDS Foundation. Because it is not government funded, there are no restrictions on whom it can serve, although it tends to focus on what Pierre-Cedric Crouch describes as clients on the “gay, bi and transmasculine spectrum.”

Crouch, who is Magnet’s director of nursing, said “half of what we do every day is PrEP. There’s a big demand.”

In an effort to serve the city’s hard-to-reach populations, the foundation kicked off a weekly event that allows queer and trans people of color to get tested for HIV and receive PrEP on the spot.

But the most difficult people to reach for HIV prevention and care are homeless.

Although homeless people make up just 1% of the city’s population, they account for 14% of the newly diagnosed HIV cases, according to the health department. While 70% of housed people with HIV have the virus under control, only a third of homeless people do.

Ebony, Dacquri and their 9-year-old son have bounced among shelters and friends’ sofas, the occasional motel and the street for at least the last nine months.

Both women are HIV-positive. Ebony has diabetes and untreated Stage 4 cervical cancer.

For a week in mid-February, they had had a motel room paid for them in the Mission District. But when that week ended, they didn’t know what to do.

For people infected with HIV, homelessness can mean the difference between sickness and health. If you have no roof over your head, your medication can get lost or stolen or confiscated in a police sweep. If you do not know where your next meal will come from, keeping a doctor appointment isn’t the highest priority.

So at 9 a.m on a rainy Thursday, the two women called Midori Harvey, an outreach worker with a program called LINCS, which connects people with HIV who have fallen out of care to clinics and medication.

Harvey, who has worked with the family since August, helped persuade the women to go on antiretroviral therapy and got them on a list for more permanent shelter. But the wait is long.

At 4 p.m., Dacquri, 32, and her son stood on Grove Street outside the Compass Family Services office. The family’s belongings lay piled on the damp sidewalk. Ebony, who is 36, was inside trying to get a place for the night.

“Our health ain’t that good,” Dacquri said. “Our boy can’t be out here in the cold.”

Ebony burst out of the Compass office, holding their little black dog. They had secured a motel room for another week.

“I have my fingers crossed until something better comes along,” Ebony said.

Something to call a home. Let their son enroll in school.

Hold the virus at bay.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.