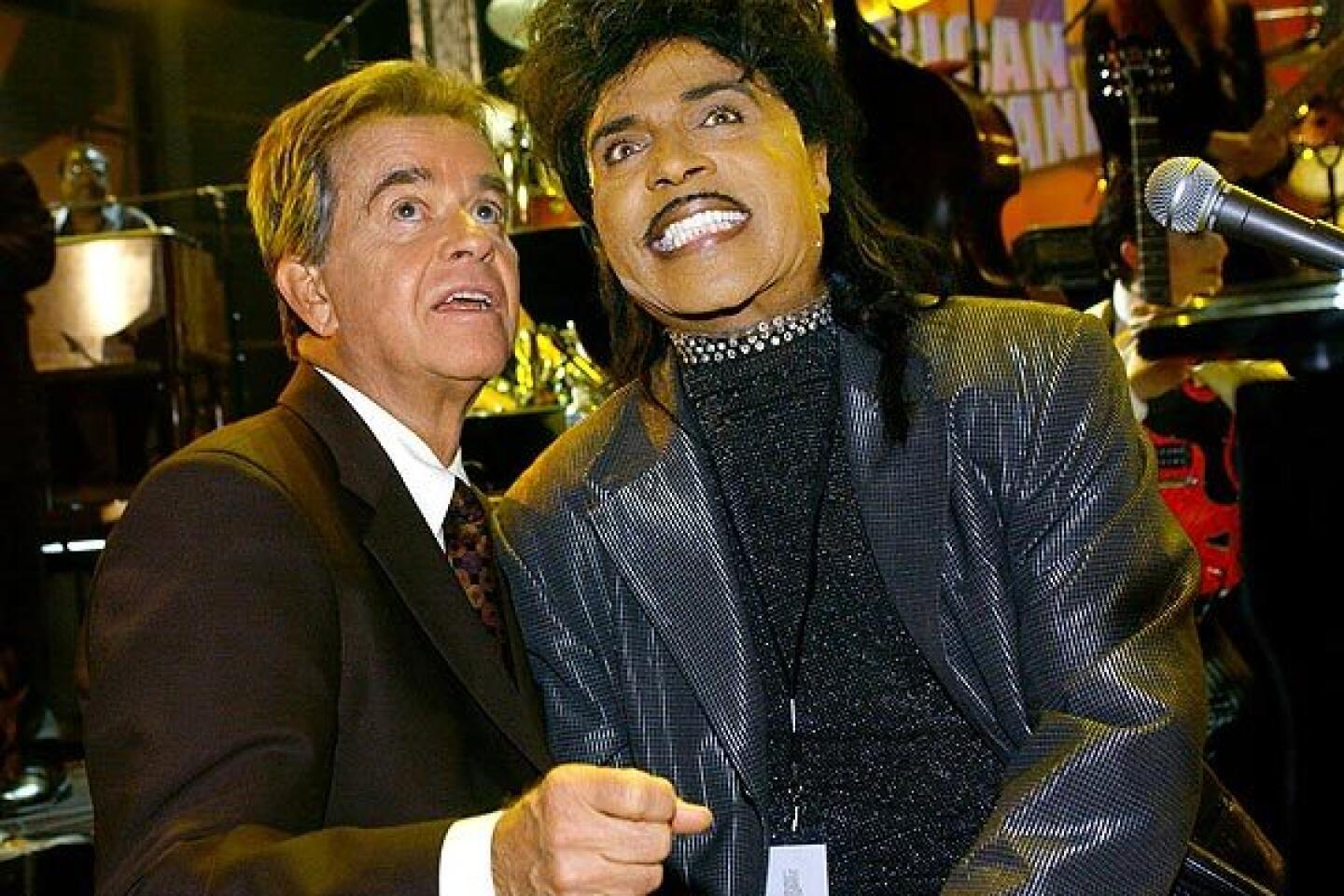

Dick Clark dies at 82; he introduced America to rock ‘n’ roll

- Share via

Dick Clark, the youthful-looking television personality who literally introduced rock ‘n’ roll to much of the nation on “American Bandstand” and for four decades was the first and last voice many Americans heard each year with his New Year’s Eve countdowns, died Wednesday. He was 82.

Clark died after suffering a heart attack following an outpatient procedure at St. John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, according to a statement by his longtime publicist, Paul Shefrin. Clark’s health had been in question since a 2004 stroke affected his speech and mobility, but that year’s Dec. 31 countdown was the only one he missed since he started the annual rite during the Nixon years.

With the exception of Elvis Presley, Clark was considered by many to be the person most responsible for the bonfire spread of rock ‘n’ roll across the country in the late 1950s. “Bandstand” gave fans a way to hear and see rock’s emerging idols in a way that radio and magazines could not. It made Clark a household name and gave him the foundation for a shrewdly pursued broadcasting career that made him wealthy, powerful and present in American television for half a century.

Nicknamed “America’s oldest teenager” for his fresh-scrubbed look, Clark and “American Bandstand” not only gave young fans what they wanted, it gave their parents a measure of assurance that this new music craze was not as scruffy or as scary as they feared. Buttoned-down and always upbeat, polite and polished, Clark came across more like an articulate graduate student than a carnival barker.

He helped transform rock ‘n’ roll into a cultural force, and in the beginning he did it by introducing artists such as Chuck Berry, Bill Haley and the Comets, James Brown, Buddy Holly and the Everly Brothers for the first time. All made their national television debuts on “Bandstand.”

As the music matured through the years, Clark played a potent role in star-shaping, and the Mamas and the Papas and Madonna would join the long and eclectic list of performers who got that first big boost on “Bandstand.” Clark himself joined many of his show’s guests in 1993 when he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

On Aug. 5, 1957, from the no-frills Studio B of WFIL-TV on Market Street in Philadelphia, Clark greeted a national television audience for the first time with the backdrop of a faux record store, a concrete floor and crowd of giddy teens in clean-cut mode: Ties for boys, no slacks for girls and no gum chewing were the rules from the first day.

By the end of 1958, it was a full-fledged sensation with 40 million viewers tuning in to ABC to learn about the newest dance step, rock star or fashion style.

The first record on the premiere show was the then-shocking single “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going On” by the ribald Jerry Lee Lewis. The juxtaposition of bracing music such as that with the show’s tame trappings — party games, a roll call of giggling kids, viewer voting on the best couple — would do more to put the emerging music into the mainstream than any other forum of the day.

While Clark embodied a “safe” aura on camera, off camera he was the prototype for the fledgling music scene’s new-model impresario. There would be close to three dozen songs played on the show on any given day and Clark huddled constantly with record executives and his own staff to decide which tunes got the highly coveted airtime.

By 1959, there was grumbling in the industry that “Bandstand” was too beholden to Philadelphia interests, particularly those that intersected with Clark’s growing portfolio of companies. From a hit record’s birth in the vinyl-pressing shop to its christening on the radio station turntable, Clark had a stake in its business life.

For the fans watching at home, Clark was simply the chaperon on their first date with rock ‘n’ roll.

“It’s got a great beat and you can dance to it,” or some permutation of that phrase, became the mantra of fan life during the “Bandstand” tradition of rating records. Three records would be played and members of the show’s dancing brigade would give them a numeric grade anywhere between the odd parameters of 35 and 98. Clark would announce the average, and fame and fortunes could be decided with that calculation.

That staple feature, along with the lip-syncing appearances by new stars and the countdown of the day’s hits made the show the template for the entire new television sector of music shows. “Soul Train,” “Solid Gold,” “America’s Top 10” and MTV’s “Total Request Live” were among the shows that would borrow from the formula. To artists, especially in the show’s first decade, a booking on “Bandstand” was a stamp of career arrival.

The only stars Clark coveted for his show in those early years but could not get were the Beatles and Ricky Nelson (the latter because of television appearance limitations set down by his contract with “The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet”). In 1959, the show finally got Presley but only for an interview, not a performance.

Michael Uslan, a Hollywood producer (“Constantine”) and former pop-culture studies professor at Indiana University, coauthored the 1981 book “Dick Clark’s The First 25 Years of Rock & Roll.” In his view, the great achievement of “Bandstand” was gathering up the dances and regional sounds of the country and presenting them to teens “on a silver platter that helped turn rock ‘n’ roll into one national thing, as we think of today.”

Uslan said Clark was well aware of the need to soften the rough edges of the music on his show.

“Dick Clark was a primary force in legitimizing rock ‘n’ roll,” Uslan said. “He was able to use his unparalleled communication skills to present it in a way that it was palatable to parents and the establishment. Dick’s philosophy was that it was like introducing someone to hot, spicy Mexican food. He would say, ‘Start them out with the mild stuff first, and once they get a taste for it they’ll jump in for the really hot stuff, the authentic stuff.’ ”

Clark would host “Bandstand” until 1989, leaving just a few months before the show’s cancellation. Its impact had waned in the era of music videos and MTV, but Clark, the show’s signature name, endured in his role as the unofficial emcee of American broadcasting.

In his New Year’s Eve broadcasts, launched in 1972, he counted down the last moments of the year from Times Square in Manhattan. He found a surprise hit in the 1980s with “TV’s Bloopers & Practical Jokes,” a franchise that correctly banked on the appeal of Hollywood stars flubbing their lines. His work and investments went into game shows, among them “The $25,000 Pyramid” and “Scattergories,” as well as television movies such as “Murder in Texas” and “Elvis!”

One of Clark’s most telling ventures was in the awards show sector.

In 1974, a dispute between ABC and the organizers of the Grammys led to an opening that Clark recognized as new turf for his music and television expertise. ABC had balked at the plan to broadcast the Grammys from Nashville, so the network and the venerable gala divorced. Clark and ABC filled the void with the American Music Awards. The AMAs, unlike the Grammys, judges its winners based on sales data and public surveys, which seemed to suit Clark’s old “Bandstand” tradition of letting the kids grade the songs.

The AMAs became a template for Clark; his production company’s banner flies now over the Emmy Awards, the Golden Globes, the Academy of Country Music Awards and the Family Television Awards.

Clark returned again and again to the legacy of his beloved “Bandstand” with numerous archival projects and tie-ins, including television specials, home video compilations and even a small restaurant chain that includes “American Bandstand” airport eateries in Indianapolis and Newark, N.J.

In 1981, with “Bandstand” entering its twilight, Clark told The Times that the show was No. 1 on his personal career countdown. “I feel about ‘American Bandstand’ the way I would about a member of my family. I’m sentimental about it. It was the beginning of everything for me.”

Thirty-seven years after its founding, Dick Clark Productions Inc. was sold in 2002 for $136 million to a group of private investors. Clark stayed on as chairman and chief executive.

Clark’s workload never let up until his stroke, which he suffered at his Malibu home. As much as his face and voice were instantly recognizable to television watchers, within the industry itself it was Clark’s drive and demanding ways that defined his persona.

A “tyrant with a stopwatch” was the appraisal of one longtime employee who had weathered many of Clark’s scoldings in the stage wings over a show portion that ran too long or too short or otherwise failed to meet his expectations.

“Can I be a mean mother? That’s absolutely true,” Clark told The Times in 1981. “My temper has gotten a little bit better but it’s still notorious. I have no patience. If I have something on my mind, I blow up. It’s my way of keeping sanity.”

That temper fueled an especially public feud with C. Michael Greene, the former chief of the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences and the guiding hand behind the Grammys. The Grammys thundered past the American Music Awards in ratings during Greene’s tenure, and one of his tactics was spreading the word that any artist who performed on the AMAs would be banned from the Grammys. Clark responded with public rage and a lawsuit. Clark dropped the suit when Greene left the academy post in 2002 after a successful but tumultuous 13-year reign.

The stories of Clark as a backstage ogre are numerous, but there are also numerous tales of envelopes of cash made for employees or former colleagues in need.

Richard Wagstaff Clark was born in Mount Vernon, N.Y., on Nov. 30, 1929. Thirteen years later, he was in the audience in a New York City theater where Jimmy Durante and Garry Moore were broadcasting a radio program. On the spot he decided that he wanted his own future to include a microphone and an audience. His focus even as a teen was enough to sway his father into a career turn of his own.

“When he found out I wanted to be in radio he quit his job,” Clark once said on CNN’s “Larry King Live.” “He was in the cosmetics business. And my uncle was opening a radio station and he said, ‘Dick’ — my father Dick — ‘come on up and run this place. It needs a good sales manager and you can do it hands down.’ So [my father] is thinking he’s a little fed up with New York City. And he moved upstate. He was thinking, run the radio station and maybe help the kid and, lo and behold, he did.”

The station was WRUN in Utica and Clark’s family connection was enough to earn him a job in the mailroom. Soon, though, he was on the air handling news bulletins and weather reports. He was 17 when he finally found an audience, albeit a modestly sized one.

Clark studied advertising and radio at Syracuse University, and he took equal interest in the handling of ledgers and on-air interviews. By 1952 he had moved to the far more dynamic Philadelphia market and was honing his craft at the WFIL/WFIO radio and television stations. The TV station’s afternoon slate of shows included a dance show called “Bandstand” with a host named Bob Horn who was popular with sponsors — until his 1956 drunk driving arrest.

The smooth-speaking and youthful-looking Clark was handling a similar radio program called “Caravan of Music” and had made his television debut as the unlikely host of a country music show stuck with the name “Cactus Dick and the Santa Fe Riders.” Clark had already aspired to make the leap to “Bandstand,” according to John A. Jackson, author of “American Bandstand,” a book on Clark’s empire. The book cites a peer of Clark’s who said the young broadcaster coveted the rock ‘n’ roll show: “I’m gonna have that show and that’s all there is to it. That will be mine.”

Clark did get the show, and it turned out to be a historic promotion for him and for rock ‘n’ roll.

The show was a hit locally and Clark enjoyed working with the young fans who would come on the show to dance. He chatted them up with a comfort that set the show apart from others of its ilk that came off as condescending or clumsy.

The music was not his favorite — he had been a jazz aficionado — but he saw its growth potential. In 1957, he heard in the office that the ABC network was looking for a new Sunday program, so he went to New York City with a kinescope copy of “Bandstand” and met with executives Dan Melnick and Jim Aubrey. (The latter would go on to be chief of CBS.) Melnick saw something in the simple formula that might click with kids watching on the weekend, and a memo he penned earned “Bandstand” a seven-week trial on the network.

The daily show hit No. 1 in the ratings within a month. In 1957 the show got a brief run in prime time on Mondays, but after a few months it reverted to five afternoon shows during the week.

Clark was thinking long-term. Worried that the youth-conscious broadcasting world might someday force him into a reluctant retirement, he launched his production company to ensure that he would always have a business to fall back on.

Clark’s savvy business eye and increasingly attuned pop ear took him into wider music pursuits. He used “Bandstand” as a foundation for new roles as artist manager, music publisher and running record-pressing plants and a distribution business.

He had partial rights to more than 100 songs and had his name on the financial paperwork of more than 30 music-related businesses. Clark also got artists to sign releases that gave him ownership of the footage of their appearances on the show, clips that have been repackaged often.

It was Clark’s interests in the radio industry that would lead to the most turbulent chapter of his success story. “Payola” was a term that was becoming part of the national vocabulary in 1960 as congressional hearings were set to investigate the music industry practice of paying disc jockeys to play particular records.

Clark was called to testify and admitted that he had accepted a fur stole and jewelry from a record executive. He avoided any substantive penalty even though peers, such as famed disc jockey Alan Freed, found their careers in tatters.

Clark said he never accepted money to play music and that his entrepreneurship was in keeping with the practices of the day in the nascent sector.

Regardless, ABC, knowing the value of “Bandstand,” told him to either sell off his conflicting business holdings or the show. Clark opted to keep his core job.

Clark’s radio life was submerged but returned years later after the business landscape had been altered. In 1981 he partnered with radio executive Nick Verbitsky to form a company called United Stations, and its flagship program would be “Dick Clark’s Rock, Roll and Remember,” an oldies show that would last more than two decades on the air.

That incarnation of United Stations did not fare as well as Clark’s radio show and was in mothballs by the 1990s. He and Verbitsky tried again in 1994 and, after acquisitions, mergers and partnerships, the United Stations Radio Networks now bills itself as the nation’s largest independently owned and operated radio network and provides programming in one form or another to 4,000 stations.

After “Bandstand,” Clark’s most famous stage mark might be in Times Square, where he helped ring in a new broadcast tradition in 1972. Until then, the most notable broadcasting fare for the New Year’s holiday was CBS’ broadcast from the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in Manhattan, where Guy Lombardo and his orchestra would celebrate with ballroom dancing and their signature rendition of “Auld Lang Syne.”

“It was terribly boring to me,” Clark told Newsday in 2003. “I wanted to make New Year’s Eve a little more contemporary and exciting.” The result was the ABC show that played to younger rhythms. The show retained Clark’s name, but in recent years Ryan Seacrest was the host.

Clark’s admiration of Arthur Godfrey prompted several forays into the variety show genre, but it proved to be a tough arena with several short-lived ventures. He did score a success with “The Donny and Marie Show” in the 1970s, which made the Osmond brother-and-sister team national stars.

Clark’s business holdings continued to be a variety show of a different sort. The desire to expand his imprint never flagged. Not only did Clark’s love of New York theater tug him into the role of a Broadway producer, his fondness for Krispy Kreme doughnuts prompted him to badger the company’s leadership until he was granted the franchisee rights in Britain and Ireland. He is the credited author or co-author of no less than a dozen books, among them guides to music, grooming and diet.

In 2004, he added a different sort of spokesman role when he acknowledged publicly that a decade earlier he had been diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. That appearance was part of Clark’s new role as a famous face for a public-awareness campaign sponsored by the American Assn. of Diabetes Educators and Merck & Co., the pharmaceutical giant.

Clark is survived by his wife, Kari Wigton Clark, whom he married in 1977. He is also survived by his children from two previous marriages, sons Richard and Duane and daughter Cindy.

.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.