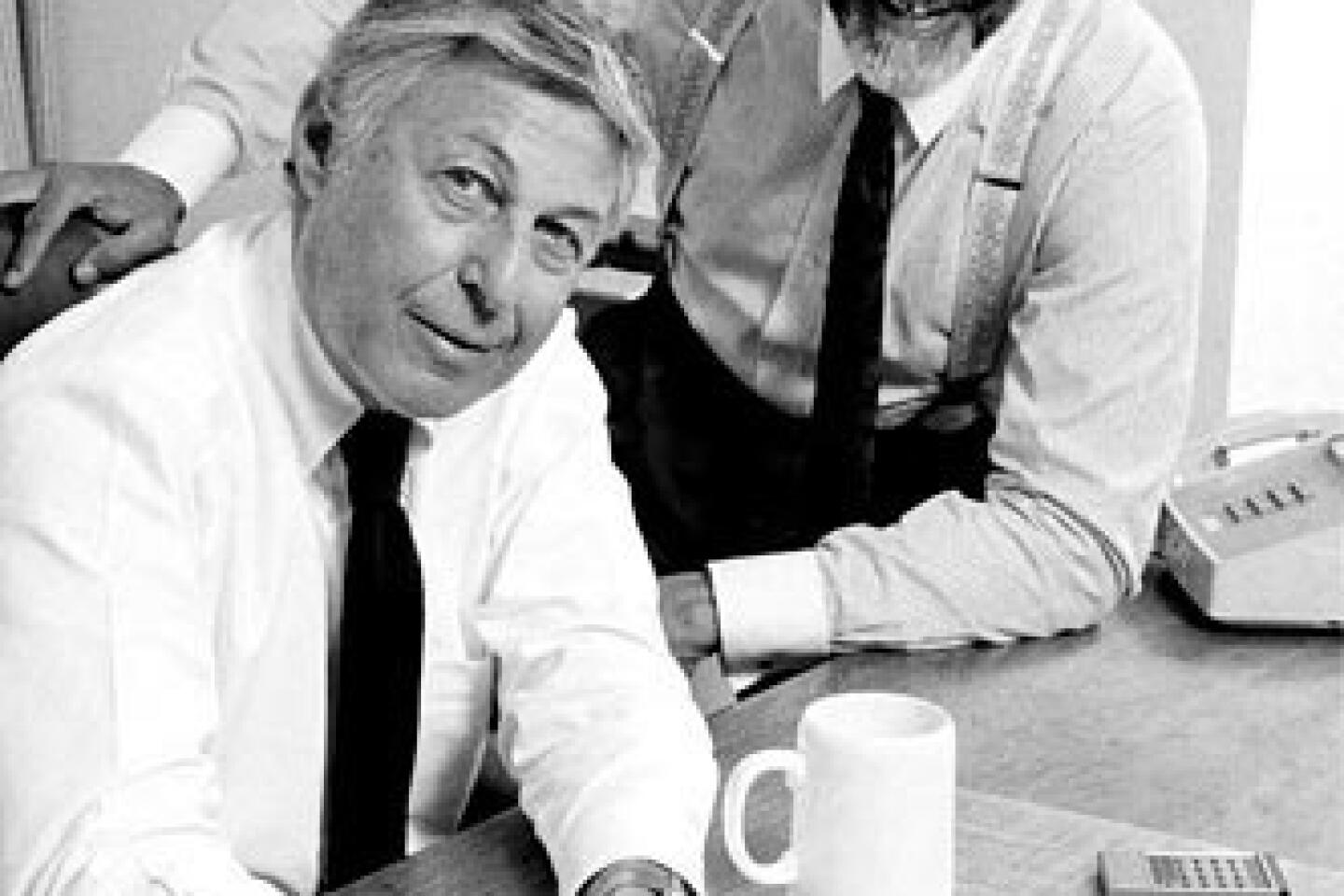

Don Hewitt dies at 86; creator of ’60 Minutes’

- Share via

It began at 10 p.m. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 1968.

“Good evening. This is ’60 Minutes,’ ” Harry Reasoner said into the camera.

With fellow correspondent Mike Wallace seated next to him, Reasoner explained the concept of the new show -- one that had the flexibility and diversity of a magazine, adapted to broadcast journalism.

FOR THE RECORD:

Hewitt obituary: An obituary of CBS news executive Don Hewitt in Thursday’s Section A said his father worked for the Boston Herald American. When Hewitt’s father worked for the newspaper, it was called the Boston American. —

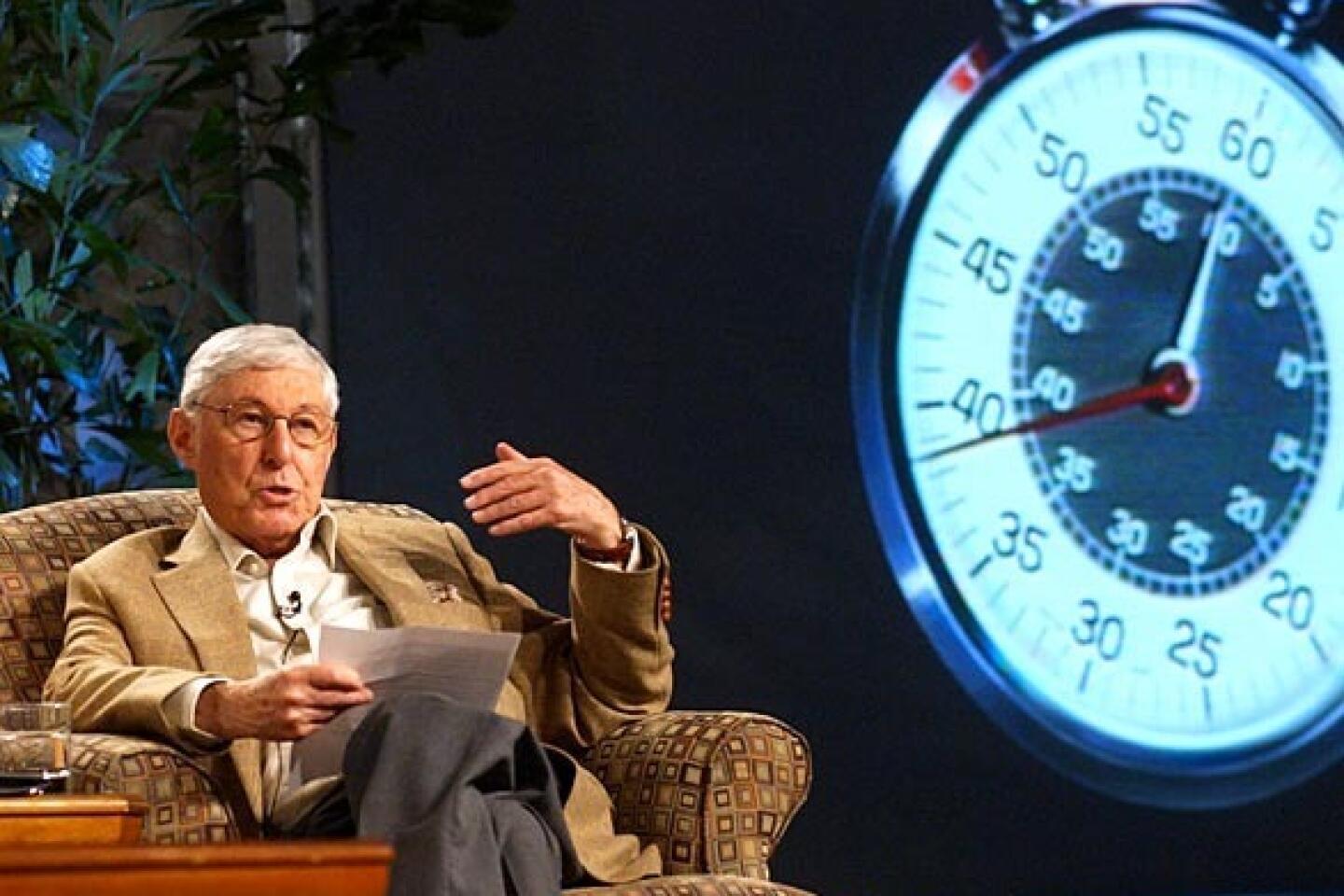

The show with the iconic ticking stopwatch launched the TV newsmagazine genre and later became a Sunday evening ritual for millions of viewers.

“60 Minutes” was the brainchild of Don Hewitt, the show’s longtime executive producer, who died Wednesday of pancreatic cancer at his home in Bridgehampton, N.Y., at age 86.

Hewitt’s new brand of TV journalism offered a mix of exposes, human-interest stories and profiles, and spawned a flood of imitators, including ABC’s “20/20” and NBC’s “Dateline.”

“I unashamedly admit I stole this program lock, stock and barrel, from Life magazine,” he told The Times in 1980. “It’s an illustrated anthology.”

And, in time, it became the top-rated show on television.

“ ‘60 Minutes” became the television viewer’s “Sunday absolution,” Av Westin, a former executive producer of “20/20” and a former ABC News executive who worked with Hewitt at CBS, said Wednesday.

“Even if you hadn’t read a book or a newspaper all week, if you saw ’60 Minutes,’ the next morning at the water cooler, you could say, ‘I am informed,’ ” he said. “It really became kind of a visceral attraction that people couldn’t miss.”

Bill Small, who served as a top executive at CBS News and NBC News, said that when “60 Minutes” began taking off in the ratings, “the other networks said, ‘We ought to do something like that.’ All the magazine shows -- even the lightweight entertainment shows -- owe their roots to what Hewitt was doing.”

In the process, “60 Minutes” turned its correspondents -- Wallace, Reasoner, Morley Safer, Dan Rather and Lesley Stahl among others -- and the man behind the scenes -- into household names.

Respected innovator

Hewitt was already a highly respected TV newsman.

In a television career that started in 1948, when he began his association with CBS as an associate director on the network’s evening news show, Hewitt’s numerous accomplishments earned him a place in the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences’ Hall of Fame in 1990.

Among them:

He produced and directed what ultimately became known as “Douglas Edwards With the News” from 1949 to 1962 and was executive producer the first year of the ensuing “CBS Evening News With Walter Cronkite,” during which the traditional 15-minute news broadcast was expanded to 30 minutes.

He also directed CBS’ early coverage of the national political conventions, beginning with the first televised convention in 1948.

And more famously, he produced and directed the first televised presidential debate, between Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy, in 1960.

Nixon, who prior to the debate had been hospitalized for a knee injury, turned down Hewitt’s offer of the services of a makeup artist to cover his sallow complexion and 5 o’clock shadow after the tanned and fit Kennedy declined.

The historic debate, in which TV viewers generally considered Kennedy the winner while radio listeners felt Nixon had won, established the power of television in national politics.

After heading a new documentary unit at CBS in the mid-1960s, Hewitt created “60 Minutes,” his most successful, acclaimed and profitable program, which he executive-produced for 36 years.

Former Times television critic Howard Rosenberg once described Hewitt as “an extraordinary TV bossman/showman, a tough, blunt, imaginative and spit-in-your-eye deliverer of highly watchable journalism and highly bankable ratings.”

In May 1980, “60 Minutes” was the No. 1 show of the 1979-80 season -- a feat it would achieve five times during Hewitt’s reign.

As Hewitt once told Rolling Stone magazine: “The trick is to grab the viewer by the throat, not let his mind wander and start thinking about what else might be going on.”

Once characterized in the Washington Post as loud, pugnacious, spleeny “and having the attention span of a hummingbird,” Hewitt shunned formal editorial meetings. “If we had meetings, the show would look like a meeting,” he reasoned. He was known for telling his correspondents and producers to “just tell me a story.”

Behind the scenes, Hewitt also was well-known for his screaming matches with his big-name correspondents, a form of verbal combat that Safer once described as “mutual torture sessions.”

Tough but fair

“He was a tough, tough editor, and all of us who worked with him had some of the worst arguments -- practically blood-on-the-floor arguments -- over stories and how they’re covered,” Safer told The Times on Wednesday. “But he had a remarkable gift. Fifteen minutes later, it was as if it had never happened. There was no grudge.

“It will not surprise you to learn there’s a fair amount of ego-inflating in this office and, I dare say, I can include myself and certainly Don. But he was wonderfully fair in whatever glory was heaped on CBS News or on him or ’60 Minutes.’ He was very generous about sharing it. And he stood up for his guys.”

Hewitt’s death came a month after that of another CBS News icon, Walter Cronkite.

“It was a rough couple of weeks with Walter going, two really terrific but totally different people,” said Safer, who described Hewitt as an old-fashioned, “Front Page”-style journalist who functioned “by the seat of his pants.”

“He was just a great, legendary editor,” Safer said. “And Don’s hands on a story always made it leaner, tougher, more direct and more readily understandable. Which is the job of an editor, and he was absolutely superb at it.”

Hewitt was born Dec. 14, 1922, in New York City, but his family soon moved to Boston, where his father worked as the classified advertising manager for the Boston Herald American. By the time Hewitt was 6, his family was living in New Rochelle, N.Y.

Inspired by maverick, big-city reporter Hildy Johnson in the newspaper comedy “The Front Page,” the 8-year-old Hewitt hatched his dream of becoming a newspaper reporter.

After graduating from high school in 1940, he attended New York University on a track scholarship. But he dropped out in the middle of his sophomore year and took a $15-a-week job as a late-shift copy boy at the New York Herald Tribune. He also worked days as a reporter and editor for a weekly newspaper in Pelham, N.Y.

During World War II, Hewitt crossed the Atlantic in a convoy of cargo ships as a U.S. Merchant Marine Academy cadet and then got a job in London covering the Merchant Marine for Stars and Stripes newspaper. He later returned to sea as an ensign in the Naval Reserve.

In 1948, he was working in Manhattan as the night telephoto editor for Acme Newspictures, the photo arm of United Press, when a friend who worked for CBS Radio told him that he had heard about an opening for someone with picture experience at CBS’ fledgling TV network.

Hewitt took a pay cut for the $80-a-week job as an associate director on CBS’ live, 15-minute nightly newscast.

Six months later, he became a director and, before long, the sole director and producer of what came to be called “Douglas Edwards With the News.”

Hewitt, who was known for having an “idea-a-minute personality,” was responsible for a number of TV news innovations.

To keep Edwards from staring at his script during his live news broadcast, Hewitt had the script written on poster boards, which were held up next to the side of the camera. (The much more efficient TelePrompTer did not arrive until later.)

One of his biggest innovations came during the 1952 Republican National Convention in Chicago: the idea of superimposing on the lower portion of the screen the names and identities of the politicians who appeared on camera. The technique, later known as a “chyron” or “super,” became standard practice for all news broadcasts.

In the 1950s, Hewitt also produced and directed CBS News programs such as Edward R. Murrow’s “See It Now” and “Person to Person,” as well as the prestigious cultural series “Omnibus.”

In his dogged attempt to deliver great TV to viewers, Hewitt in 1956 talked a Navy helicopter pilot into flying him, Edwards and a film crew out to the luxury liner Andrea Doria, which had collided with another ship in the North Atlantic. They wound up getting footage of the liner as it disappeared into the ocean.

“That night,” he later wrote, “CBS News had its biggest exclusive of the year.”

Hewitt, however, was known to rankle his CBS News bosses with his sometimes unorthodox methods. That included once making an off-camera obscene gesture at prisoners to get them angry enough to re-create the scene of a New Jersey prison riot for his cameras after the riot had ended.

With Cronkite in frequent conflict with Hewitt over their differing approaches to the news -- and with “CBS Evening News With Walter Cronkite” losing the ratings battle to NBC’s “The Huntley-Brinkley Report” -- Hewitt was removed as executive producer in late 1964.

Special unit

Fred Friendly, the network’s news division president, then gave Hewitt his own “special unit” to produce live programs and documentaries around the world.

During this time, Hewitt turned out programs such as “Town Meeting of the World,” a series in which prominent international figures sat for discussions and interviews.

He also produced one of his finest hours of television, an intimate documentary profile of Frank Sinatra.

But Hewitt felt as though he was “in limbo” during this period.

Then came “60 Minutes.”

Over the years, the show featured countless memorable stories, including an investigation into the slaughter of Kenyan elephants for their tusks, a profile of Johnny Carson and a 1992 interview with presidential candidate Bill Clinton in which Clinton addressed questions of marital infidelity.

When asked what he considered the finest hour for the program, Hewitt would mention Safer’s award-winning 1983 report on Lenell Geter. An engineer who had been wrongly convicted of armed robbery and sentenced to a life term in Texas, Geter was freed a few days after Safer discredited the evidence that had put him behind bars.

The pioneer newsmagazine has received scores of Emmys and other prestigious awards. But it also received its share of criticism, including charges of bias, distortion, sensationalism and theatricality.

Hewitt’s darkest hour came in 1995 when he failed to resist CBS management’s decision to shelve a Wallace interview with whistle-blower Jeffrey Wigand, the former vice president of research and development at Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. who agreed to go on camera with incriminating charges against his former employer regarding the dangers and addictive nature of its products.

Wigand had signed a confidentiality agreement with the tobacco company that prohibited him from revealing inside information.

Any attempt by CBS to induce Wigand to break the contract, the network was advised by its lawyers, could lead to a multibillion-dollar lawsuit that would put the network in jeopardy.

Hewitt, who stated publicly that “we’ve got a story we think is solid,” nevertheless sided with the network’s decision not to broadcast the interview -- a stance for which he was criticized by many fellow journalists.

“It was not my proudest moment,” Hewitt conceded in “Don Hewitt: 90 Minutes on ’60 Minutes,’ ” a 1998 segment of “American Masters” on PBS.

In November 1995, “60 Minutes” did broadcast a segment on the bind the story had put them in, without naming Wigand and the company he had worked for by name, as well as reporting what Hewitt later called “all the salient facts we had learned about the chicanery of the tobacco companies.”

And three months later, after the Wigand story went public when the Wall Street Journal published an account of his testimony in a Mississippi court case and revealed Brown & Williamson’s campaign to undermine Wigand’s credibility, “60 Minutes” aired its Wigand segment.

“The Insider,” a 1999 movie based on the incident, starred Al Pacino and Russell Crowe, with Philip Baker Hall as Hewitt.

In 2004, 36 years after launching “60 Minutes,” the 81-year-old Hewitt was forced to turn over the reins to 49-year-old Jeffrey Fager.

Despite his reluctant departure from “60 Minutes,” Hewitt did not retire.

He simply moved a floor below his ninth-floor office on West 57th Street in Manhattan,where he continued as executive producer of CBS News. In recent years, he was involved in projects outside of CBS.

He is survived by his third wife, former television news correspondent Marilyn Berger; his sons, Steven and Jeffrey; his daughter, Lisa Cassara; his stepdaughter, Jilian Childers Hewitt, whom Hewitt adopted; and three grandchildren.

Hewitt never lost his love for the news business, recalling in his 2001 memoir “Tell Me a Story: Fifty Years and 60 Minutes in Television” how he felt when he was hired for his copy boy job at the New York Herald Tribune.

“I know it sounds corny,” he wrote, “but when I walked into that building on 41st Street and heard the presses, I thought I had died and gone to heaven.”

Times staff writer Matea Gold contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.