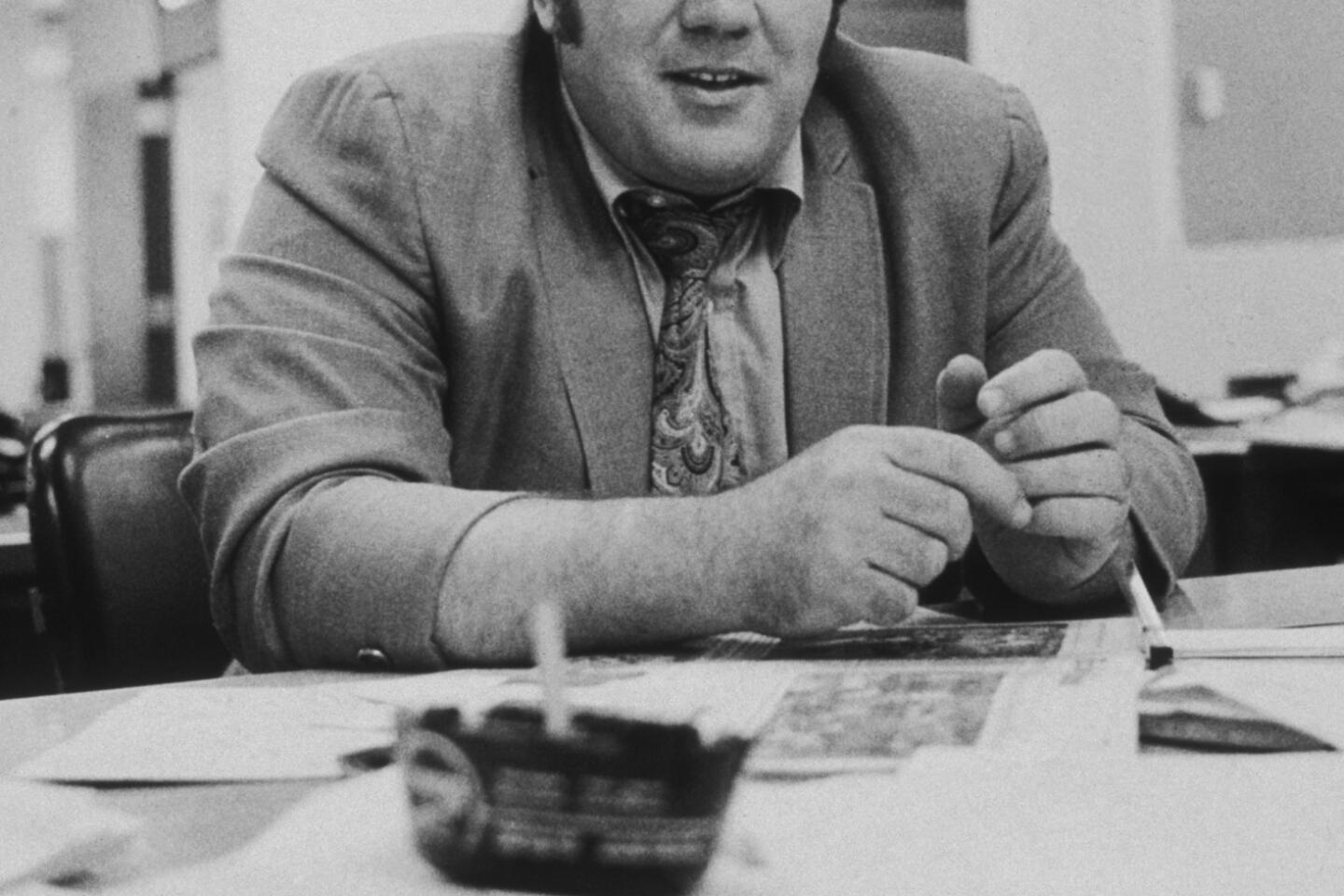

Jimmy Breslin, legendary New York City columnist, dies at 88

- Share via

Jimmy Breslin, the street-savvy, Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper columnist whose two-fisted prose championing the little guy and pillorying those who betrayed the public trust made him a New York City institution for more than 40 years, died Sunday. He was 88.

Breslin, who also turned out a string of fiction and nonfiction books, died of complications from pneumonia, the Associated Press reported, citing his stepdaughter, Emily Eldridge.

For the record:

5:06 p.m. Jan. 22, 2025An earlier version of this article said Jimmy Breslin died at the age of 87. He was 88.

A self-described “unlettered bum” from the borough of Queens who nevertheless was known to read Dostoevsky for relaxation, Breslin launched his career as a columnist at the New York Herald Tribune in 1963.

From start to finish — at Newsday, where his last regular column ran on election day in 2004 — the stocky, loud and aggressive writer vividly captured what he considered “the only city in the world worth talking about.”

Los Angeles Times columnist Jack Smith once described Breslin’s writing style as being “like an Irish wind that has blown through Queens and Harlem and Mutchie’s bar. It is a pound of Hemingway and a pound of Joyce and 240 pounds of Breslin.”

Breslin was part of the wave of practitioners of what came to be known as New Journalism: a group of gifted writers that included Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Hunter S. Thompson, Joan Didion and others who reported on the social and cultural upheavals of the 1960s and ’70s in newspaper and magazine journalism that read like good fiction.

“I never thought about how to do a column,” Breslin told Marc Weingarten, author of “The Gang That Wouldn’t Write Straight,” a 2006 book about the New Journalism revolution. “It just came naturally, I guess. It had a point of view and it had to spring right out of the news.”

There is, Breslin added, “an immediacy that makes the column fresh. Like you were covering the eighth race at Belmont. But no one was doing it when I started. That’s why everyone thought it was new.”

“Jimmy was incredible, the greatest newspaper columnist of my era,” Wolfe, who was hired as a general assignment reporter at the Herald Tribune in 1961, told Weingarten. “He turned out that column five times a week, and practically all of it was reporting. He introduced Queens to New York.”

That included introducing his readers to an array of Runyonesque characters — guys such as Fat Thomas, a 450-pound bookmaker; Jerry the Booster, a shoplifter; Bad Eddie, who “doesn’t do anything nice,” and Marvin the Torch.

“Marvin the Torch never could keep his hands off somebody else’s business, particularly if the business was losing money. Now this is accepted behavior in Marvin’s profession, which is arson,” Breslin wrote.

Breslin had a diverse fan base that included David Berkowitz, the “Son of Sam” serial killer, who wrote him letters while terrorizing New Yorkers in the 1970s. “I also want to tell you,” Berkowitz wrote in one missive, “that I read your column daily and find it quite informative.”

Occasionally, Breslin’s reporting extended far beyond the Big Apple. And as a reporter, he was famous for splitting from the journalistic pack.

Immediately after President Kennedy was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963, Breslin flew to Dallas, where he interviewed the Parkland Memorial Hospital surgeon who “took charge of the hopeless job of trying to keep the 35th president of the United States from death.”

He also interviewed the Catholic priest who administered the last rites, and the funeral director who picked out a bronze casket to bear the president’s body, to write his newspaper article, headlined “A Death in Emergency Room One.”

And in Washington, D.C., on the day Kennedy was buried, Breslin ignored the pomp of the funeral procession and instead wrote about the $3.01-an-hour equipment operator at Arlington National Cemetery who was assigned to dig Kennedy’s grave.

During the ’60s, the New York Herald Tribune’s star columnist — and regular contributor to the newspaper’s renowned Sunday magazine, New York — was on the scene of many other major events, including the Alabama voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965.

Sent to Vietnam the same year, he not only filed stories on the troops in the field but reported on what black soldiers thought about the Watts riots and hung out at a racetrack with a Special Forces sergeant and the Vietnamese prostitute who accompanied him.

But it’s as a columnist covering his hometown that Breslin earned his reputation, writing in his straightforward, oftentimes humorous, prose:

“The first funeral for Andrew Goodman was at night and it was a lot of work. To begin with they had to kill him.”

I think he believes that it is his responsibility to let the voiceless have a voice.

— Pete Hamill

“Football is a game designed to keep coal miners off the streets.”

“The auditorium, named after a dead Queens politician, is windowless in honor of the secrecy in which he lived and, probably, the bank vaults he frequented.”

Breslin was a three-times-a-week columnist for the New York Daily News in 1986, when he won the Pulitzer Prize for “columns which consistently championed ordinary citizens.”

Journalism’s most prestigious award came in the wake of a string of noteworthy Breslin columns, including those in which he revealed that some of the city’s cops were using “stun guns” to get confessions, that there was widespread bribery in the city’s parking bureau, and that subway vigilante Bernhard Goetz had shot two of his four black teenage victims, whom he said were about to rob him, in the back.

Breslin also had written compassionately about AIDS in his column.

“I’ve never seen him use the column against people who didn’t have power,” writer Pete Hamill, a longtime friend, told the Miami Herald in 1986. “I think he believes that it is his responsibility to let the voiceless have a voice. He’s definitely not interested in interviewing [then U.S. Secretary of State] George Shultz.”

Like Marvin the Torch or Jerry the Booster, the rumpled, Irish American bard from Queens was as much a character as anyone he wrote about.

Frustrated by his Queens neighbors constantly coming to his door to complain about his kids, Breslin had a sign installed in his front yard that proclaimed: “People I’m Not Talking to This Year.” And, as he informed readers of his column, “right under it, in neat columns, like a service honor role, was the name of everybody who lives on my block. Everybody.”

To protest the eviction of a homeless man who had been arrested and taken to Bellevue Hospital for living on a traffic island in the middle of East River Drive, Breslin took over the same spot, complete with beach umbrella, bathing suit, radio and lounge chair.

In the process of turning out his columns, magazine articles and fiction and nonfiction books, including the 1969 bestselling comic novel “The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight,” Breslin became a well-known celebrity.

He pitched Piels beer in a TV commercial (“a good drinkin’ beah”), guest-hosted a segment of “Saturday Night Live” and hosted his own TV show: “Jimmy Breslin’s People,” a one-hour, twice-weekly program that lasted 13 weeks on ABC in 1986.

Breslin also ran for council president in the city’s Democratic primary election in 1969 on a losing ticket with author Norman Mailer for mayor. Their platform: “To Make New York City the 51st State.”

Although Breslin has been described as an exacting reporter who took copious notes during interviews, he had his share of journalistic critics.

After Breslin won the Pulitzer Prize in 1986, Newsweek’s Jonathan Alter raised the issue of the columnist’s “fabled ear for dialogue,” which “has struck some colleagues as a bit too good, too epigrammatic for the way people really speak between quotation marks.”

To which Breslin irately countered: “They [other reporters] take a cop on the beat and make him sound like he’s under secretary of state! They’re the ones who make up quotes.”

He went on to defend his occasional columns that featured Marvin the Torch and other set characters as his way of giving readers a comic break from “the misery and TV oatmeal of their lives.”

In his book, Weingarten wrote that Buddy Weiss, the Herald Tribune’s managing editor, “had too much faith in Breslin’s skill as a reporter to question his veracity, but he did allow a degree of creative latitude regarding dialogue and the use of minor details to enliven some of his more fanciful set pieces.”

Breslin was born in Jamaica, Queens, on Oct. 17, 1928. His father, an alcoholic piano player, later abandoned the family. To support Breslin and his younger sister, Deirdre, their heavy-drinking mother worked as a supervisor in the welfare department.

Breslin fared poorly in school, but he loved reading the sports pages and developed an early love of writing; at age 8, he turned out a hand-printed, one-sheet newsletter filled with schoolyard gossip called the Flash.

Beginning as a copy boy at the Long Island Press in the mid-1940s before he was 16, he later attended Long Island University at night and worked a variety of reporting jobs at the paper, including covering sports. Over the next decade and a half, he worked as a sportswriter for several newspapers, including the New York Journal-American.

In 1954, Breslin married Rosemary Dattolico, with whom he had six children. In his columns, he referred to his wife as “the former Rosemary Dattolico.”

Because Breslin did not drive, he got around in taxis. He also was known to sometimes enlist his wife, who would pack their kids into her car in the middle of the night to drive him to the scene of a fire or homicide.

To help support his family, Breslin began writing books. His first, “Sunny Jim: The Life of America’s Most Beloved Horseman, James Fitzsimmons,” was published in 1962 to little notice.

But his second book, published a year later — “Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?: The Improbable Saga of the New York Mets’ First Year” — became a regional bestseller and led to his being hired by the New York Herald Tribune.

Among his more than 20 books are the novels “World Without End, Amen” and “Table Money,” the biography “Damon Runyon: A Life,” and “I Want to Thank My Brain for Remembering Me,” a memoir about his 1994 brain surgery. His last book, published in 2008, was “The Good Rat: A True Story.”

In the late ’60s, Breslin began writing for New York, the new magazine launched by editor Clay Felker, who had been editor of the by-then defunct Herald Tribune’s similarly named Sunday magazine.

Breslin’s wife of 26 years died of cancer in 1981. A year later, he married Ronnie Eldridge, an executive with New York’s Port Authority and a widow with three children, and moved from blue-collar Queens to Eldridge’s chic Central Park West apartment in Manhattan.

Breslin reportedly cut down on his drinking and smoking and began swimming for exercise. Otherwise, he remained the same: a man whom colleagues have described as profane, argumentative, arrogant, bullying and hot-tempered.

In his election day column for Newsday in November 2004, Breslin called the presidential election for Democratic Sen. John F. Kerry of Massachusetts, whom he confidently predicted would win “by a wide margin.”

Buried in his boasting, Breslin surprised his readers by noting that “I invented this column form. I now leave, but will return here for cameo appearances.”

The less-than-prophetic headline for that day’s column, referring to his prediction of a Kerry win, declared, “I’m right — again. So I quit. Beautiful.”

He signed off his last regular column for Newsday with, “Thanks for the use of the hall.”

Always a writer, he continued to turn out books, including “Branch Rickey,” a 2011 portrait of the Brooklyn Dodgers executive who broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier by signing Jackie Robinson.

Breslin had six children from his first marriage: twins James and Kevin, Rosemary, Patrick, Kelly and Christopher; and three stepchildren, Daniel, Emily and Lucy.

Breslin’s daughter Rosemary died of a rare blood disease at age 47 in 2004; Kelly died at age 44 in 2009 after collapsing at a New York City restaurant four days earlier.

McLellan is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.