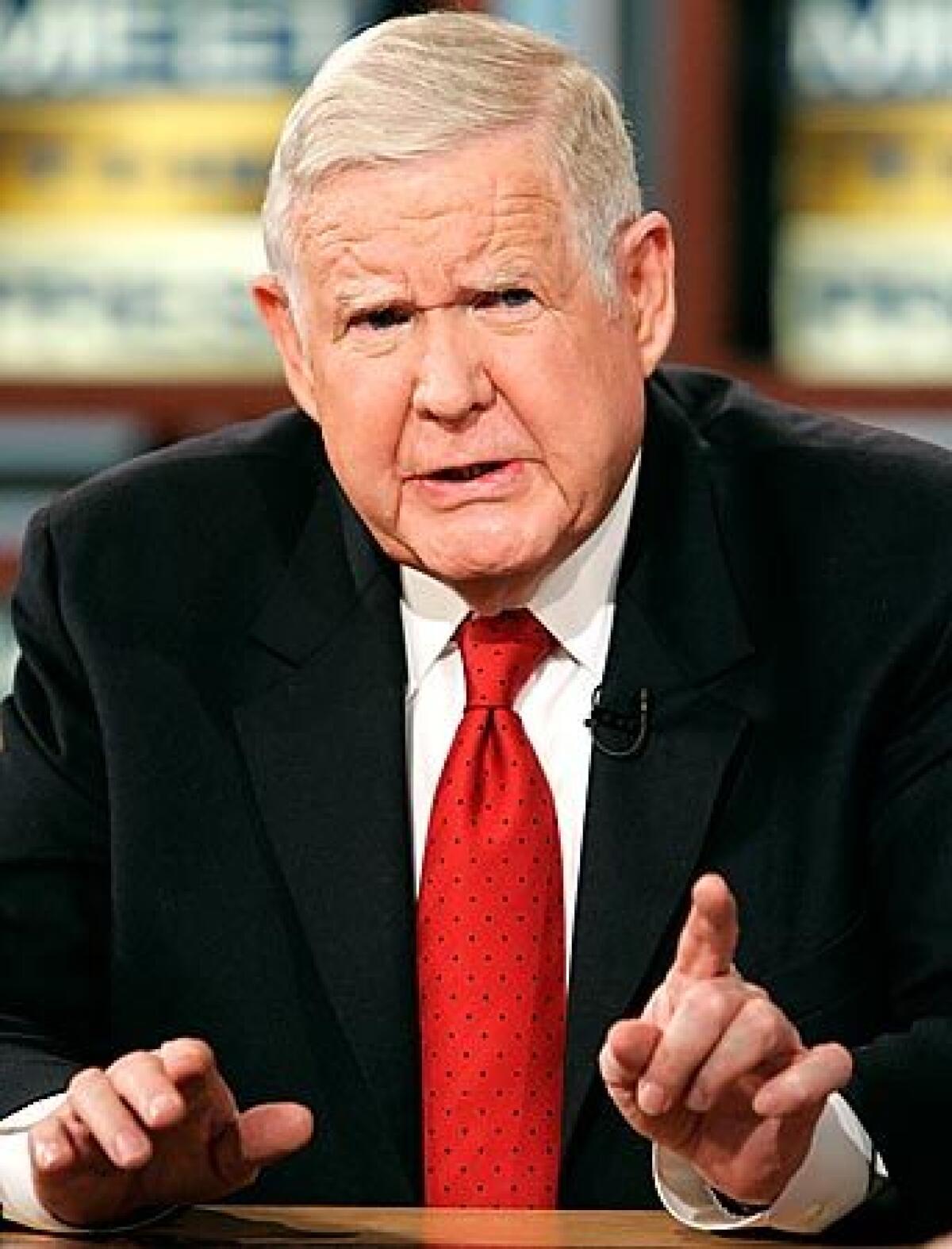

John Murtha dies at 77; Pennsylvania Democrat forcefully opposed Iraq war in Congress

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — John Murtha, the Democratic congressman from Pennsylvania and decorated former Marine whose fierce opposition to the Iraq war helped catalyze public sentiment against the conflict, died Monday. He was 77.

Murtha died at Virginia Hospital Center in Arlington, Va., surrounded by his family, his office announced. He had been hospitalized with complications from gallbladder surgery.

“With the passing of Jack Murtha, America lost a great patriot,” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said in a statement about Murtha, who was an ally of the California congresswoman.

Although his turn against the war in 2005 made him a national figure, Murtha was known inside Washington for decades as the consummate behind-the-scenes deal maker, an old-line power broker and physically imposing figure who unrepentantly delivered billions of federal dollars to his home state.

In his later years, Murtha became a favorite target of critics demanding an end to Congress’ earmarking largesse, a personification of the power of pork. Contractors and lobbyists close to him were the target of federal corruption probes. He, however, was never charged with a crime, nor found to have committed an ethical breach.

As a result, Pennsylvania’s longest-serving member of Congress leaves a complicated legacy -- praised by antiwar liberals for his courage while pilloried by government reformers.

Still, it was no small thing for the then 73-year-old Murtha, a decorated Vietnam veteran and longtime champion of the armed forces, to stand before television cameras in 2005 and call for an immediate pullout of American forces from Iraq. In doing so, he became the unlikely face of congressional opposition to the war.

“Our military’s done everything that has been asked of them,” Murtha said then. “The U.S. cannot accomplish anything further in Iraq militarily,” he said. “It’s time to bring the troops home.”

His view was, in turn, savaged by President George W. Bush and congressional Republicans and supported, but not embraced, by nervous Democrats. “Jack Murtha went out and spoke for Jack Murtha,” said Rep. Rahm Emanuel of Illinois, now the White House chief of staff, who then headed the Democratic House election effort.

John Patrick Murtha Jr. was born in New Martinsville, W.Va., on June 17, 1932, a child of the Depression. His family soon moved across the border to Pennsylvania. Military service ran in his blood: An ancestor had fought in the Revolutionary War, another with the Union Army in the Civil War. His father and three uncles served in World War II.

Murtha, too, would soon enlist, leaving college to join the Marines after the Korean War broke out in 1950. He became a drill instructor but didn’t serve overseas.

He returned to Pennsylvania to take over the family business, a car wash and a gas station, and resume his studies, earning a bachelor’s degree in economics from the University of Pittsburgh. He also joined a Marine reserve unit, then volunteered for active duty in 1966, as the war in Vietnam escalated, leaving behind his wife, Joyce, and three small children.

A major with the 1st Marine Regiment, he spent the bulk of his time in the field, overseeing intelligence operations.

Wounded twice, he was awarded two Purple Hearts, a Bronze Star and the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry.

Murtha entered politics upon his return to the United States, first securing a seat in the state Legislature and then winning a special House election in 1974, becoming the first Vietnam veteran to serve in Congress.

He immediately established himself as a Democratic hawk, voting to fund the war in Vietnam long after the national mood had soured.

During his fourth term in the House, Murtha faced a political test, becoming ensnared in the FBI’s Abscam bribery investigation. He was videotaped speaking to an FBI agent posing as a lawyer for a rich Arab sheik, refusing to take $50,000 in cash -- supposedly in exchange for help obtaining a visa for the sheik.

The Justice Department cleared him, and he testified against two other congressmen, John Murphy and Frank Thompson, who were later convicted. Murtha was reelected.

As Republicans continually mounted furious efforts to defeat him in his western Pennsylvania district, Murtha cast himself as a man who could deliver the goods back to a region devastated by the decline in the coal and steel industries. It was estimated that Murtha, in his prime as a senior member of the subcommittee that sets the Pentagon’s budget, sent more than $100 million in contracts to his district, largely through earmarks for military-related projects.

An airport near his hometown of Johnstown, Pa., is often cited by critics as evidence of his earmarking might. Despite operating only three commercial flights a day (along with some military flights), the John Murtha Johnstown-Cambria County Airport has received more than $200 million in federal funds.

In 2008, federal agents raided a lobbying firm in Washington, the PMA Group, that specialized in securing military contracts for its clients, and another firm in Johnstown that was largely funded through Murtha’s earmarks. Both donated heavily to Murtha’s reelection efforts. The investigations are ongoing, but the Office of Congressional Ethics closed a probe of Murtha in December.

The probes were concurrent with calls in the House to clean up the earmark process -- an effort that President Obama endorsed. Murtha, however, was never apologetic for using his congressional power to benefit his economically depressed home.

“If I am corrupt,” he said in a March 2009 interview with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “it is because I take care of my district.”

A special election will be held to fill Murtha’s seat, but a date has not been set.

Survivors include his wife, Joyce, whom he married in 1955; his daughter, Donna Murtha; his twin sons, John and Patrick; three grandchildren; and two brothers, Robert and James.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.