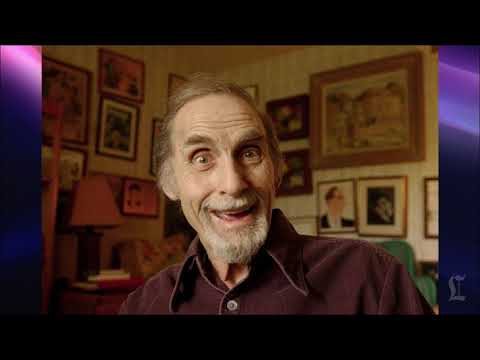

Sid Caesar dies at 91; comedy giant of the small screen

Television pioneer Sid Caesar died this week at his home in Beverly Hills after a brief illness; he was 91.

- Share via

In a day before comedy was laced with irony and studded with mean-spirited barbs, Sid Caesar was more than funny.

He was hilariously, outrageously, tear-inducingly, gather-up-the-whole-family-for-this funny.

A veteran of the Catskills with an elastic face, a knack for gibberish and a mind that could find comedy gold in the workings of a Bavarian cuckoo clock, Caesar was the king of live television sketch comedy in the 1950s.

Some of the best writers — Carl Reiner, Neil Simon and Mel Brooks — vied to work for him. No slouches at comedy themselves, they were dazzled by his genius and, at times, horrified by his temper; he once tore the sink from a hotel bathroom and threatened to throw Brooks out an 18th-story window.

Caesar went public with some of his emotional problems in 1956, long before it was common for celebrities to do so. He is best known, though, not for his tormented inner life but for the inspired zaniness of the sketches on his trademark programs, “Your Show of Shows” and “Caesar’s Hour.”

A two-time Emmy Award-winning performer, Caesar died Wednesday at his home in Beverly Hills after a brief illness, according to his biographer Eddy Friedfeld. He was 91.

“He was without a doubt the greatest monologuist, pantomimist and sketch artist that ever worked on TV,” Reiner told The Times on Wednesday. “He set the template for all the other comedians that came after him, but none could do what Sid did.”

Larry Gelbart, who wrote for “Caesar’s Hour” and some of Caesar’s TV specials, once described him as “the single most gifted man ever to grace the small screen, except when Sid was on it, it grew somewhat in size.”

With his flair for verbal and physical comedy honed while performing during his World War II service in the Coast Guard and in nightclubs and theaters after the war, Caesar burst on the national scene in 1949 as the star of the “Admiral Broadway Revue,” a live, hourlong show from New York that aired Friday nights simultaneously on NBC and the DuMont network.

The Max Liebman-produced show, which was built around Caesar and teamed him with comedic actress Imogene Coca, featured guest stars, comedy sketches and large production numbers.

The “Admiral Broadway Revue” was a hit — so much so that it was canceled after less than five months when the Admiral Corp. withdrew its sole sponsorship: It reportedly needed to use the money it had been putting into the program to build a factory to keep up with the skyrocketing number of orders for its TV sets generated by the show.

But the “Admiral Broadway Revue” was only a warmup for what Caesar later called the main event: “Your Show of Shows.”

The live, 90-minute Saturday night show, produced by Liebman and showcasing the comic ensemble of Caesar, Coca, Reiner and Howard Morris, aired from 1950 to 1954 and won two Emmys for best variety show.

Caesar later compared performing the 90-minute show live before a theater audience, without the aid of cue cards or TelePrompTers, to doing a new Broadway show each week. And they did it 39 weeks each season.

Out of that pressure cooker came innumerable classic comedy moments.

There were domestic sketches, including one in which Caesar and Coca are a married couple trying to decide how to tip at a fancy restaurant. In another, Caesar is a husband who is so anxious about a big meeting the next morning that he can’t fall asleep. But instead of taking sleeping pills, he mistakenly takes pep pills.

In one of the show’s most memorable sketches, Caesar, Coca, Reiner and Morris wordlessly played the figures on a large town clock that appear with mechanical precision on the hour, until the clock goes on the fritz.

There also were parodies of movies such as “Sunset Boulevard” and “From Here to Eternity,” as well as foreign films that displayed Caesar’s signature foreign language double talk.

Brooks, who wrote for “Your Show of Shows” and “Caesar’s Hour,” once said that Caesar “always took comedy to a stratospheric level. You’d come in and say, ‘This is the best, the best, the best,’ and he’d just come around and turn it into something better.”

Caesar later said the key to the show’s success “unquestionably was the writing.”

Among the members of the “Your Show of Shows” legendary Writers’ Room, in addition to Reiner, Simon and Brooks, were Mel Tolkin, Lucille Kallen, Tony Webster, Joe Stein and Neil Simon’s brother Danny.

“Every morning, I would walk into the room, sit down in my chair, and shoot the breeze for a few minutes with the writers,” Caesar wrote in “Caesar’s Hours: My Life in Comedy With Love and Laughter,” a 2003 book written with Friedfeld. “I then lit a cigar, which was the signal to start working, and said: ‘All right, let’s hear the brilliance.’ ”

And, he wrote, the “energy that existed inside the walls of the Writers’ Room as we created was palpable. We laughed a lot, we screamed a lot and then we hollered a lot. It was a combination of euphoria and terror.”

As the highly paid star of a hit TV show — he earned a princely $25,000 a week in the fourth season of “Your Show of Shows” — Caesar moved from Queens into an apartment on 5th Avenue. He also purchased a new black Cadillac convertible, bought dozens of handmade suits, smoked expensive Havana cigars and tipped lavishly.

But behind the visible signs of success was an insecure man who drank heavily outside work and took sedatives to sleep to deal with the pressure of doing the weekly show and his own personal demons.

His drinking at the time, Caesar later wrote, caused his underlying anger and violence to emerge.

Most famously, after a day of doing nine performances at a theater in Chicago, a drunk Caesar angrily lifted Brooks and rushed him to the open window of an 18th floor hotel room after Brooks kept insisting they go out.

“You want out? I’ll show you out,” Caesar yelled, dangling Brooks halfway out the window before Caesar’s brother, Dave, grabbed him and Brooks was pulled back into the room.

Caesar addressed some of his emotional issues and his entry into psychoanalysis in a 1956 Look magazine article.

“On stage, I could hide behind the characters and inanimate objects I created,” he wrote. “Off stage, with my real personality for all to see, I was a mess. It was difficult for me to establish a normal, healthy relationship with anyone. I couldn’t believe that anyone could like me for myself.”

The youngest of four sons, Caesar was born Sept. 8, 1922, in Yonkers, N.Y., where his Polish-immigrant father owned a luncheonette that catered to factory workers.

By the time he was in elementary school, Caesar had learned to mimic the sounds of the immigrant Italians, Russians, Poles, French, Spanish and others who ate at his father’s restaurant.

When he first demonstrated his flair for foreign language double talk — gibberish that sounded like the real thing — to the immigrant groups seated at the various tables, he had the whole room breaking up. And, he later wrote in his 1982 autobiography “Where Have I Been?” “it was the beginning of a comic device that helped me earn millions later on.”

But Caesar wasn’t thinking in terms of a career in comedy at the time. He took saxophone lessons as a child and at the age of 16, after graduating from high school in 1939, he moved to New York City. He played sax with bands there and at resort hotels in the Catskills, where he began helping the resident comics in comedy sketches.

While performing comedy at the Avon Lodge in Woodridge, N.Y., during the summer of 1942, Caesar met the niece of the owner, Florence Levy. They were married in 1943 and had three children, Michele, Rick and Karen.

While stationed at a Coast Guard base in Brooklyn during World War II, Caesar co-produced a musical revue in which he and others performed skits that satirized life on the base.

That led to performing in the revue at other Coast Guard and Navy bases. Caesar was then asked to appear in the big Coast Guard revue “Tars and Spars,” which played in theaters around the country. The revue’s civilian director was Liebman, who played a key role in Caesar’s postwar career.

While still in the Coast Guard, Caesar appeared in the 1946 movie version of “Tars and Spars.”

On the basis of his performance in “Tars and Spars,” Caesar was invited to perform for two weeks at the Copacabana nightclub in New York City, opening on New Year’s Day 1947. He went on to perform on the nightclub and movie theater-vaudeville circuit and was cast in a 1948 Broadway revue called “Make Mine Manhattan,” a hit that ran for a year.

Then came Caesar’s meteoric rise on “Admiral Broadway Revue” and “Your Show of Shows.”

“Your Show of Shows” won Emmys for best variety show in 1952 and ’53. At the end of its fourth season, however, NBC decided to drop the program and give Caesar and co-star Coca their own shows.

“The Imogene Coca Show” was canceled after a single season. But “Caesar’s Hour,” with Nanette Fabray replacing Coca, and Reiner and Morris returning as regulars, was a success.

The new show earned Caesar another Emmy in 1957, the same year the program was canceled.

In 1958, Caesar was reunited with Coca on the short-lived “Sid Caesar Invites You,” a live, half-hour comedy-variety series on ABC, and he went on to do a number of hourlong TV specials.

He starred on Broadway in 1962 in “Little Me,” playing seven characters. And he was one of the big names in director Stanley Kramer’s star-studded 1963 comedy film “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.”

But Caesar’s return to weekly television the same year was a bust: “The Sid Caesar Show,” a half-hour comedy-variety show on ABC that ended after five months.

Over the next few decades, Caesar continued to perform on stage and make occasional guest appearances on TV series and in movies such as Brooks’ “Silent Movie” and “History of the World: Part 1,” and “Grease.”

But for much of that time, his drinking and pill-taking continued to dramatically affect his life. During the first four months of 1978, he never left his house and rarely even got out of bed.

While starring in a dinner theater production in Canada that May, Caesar had trouble remembering his lines and wasn’t even sure where he was supposed to stand or sit.

It was then, while back in his dressing room, that he realized he had to decide whether he wanted to live or die.

He chose, he wrote in “Where Have I Been?” to live.

He checked into a hospital and went off booze and pills cold turkey, the first step in recovering from what he described as his own personal 20-year Great Depression.

“I survived it all — blackouts, wipeouts, falling down, disaster, disaster, disaster, because of my wife, my beautiful, steadfast wife. And my kids,” Caesar told the Boston Globe in 1992. “I’m a happy man now. Contented.”

Caesar’s wife of 67 years, Florence, died in 2010. He is survived by his daughters Michele Glad and Karen Caesar, son Richard and two grandsons.

McLellan is a former Times staff writer. Times staff writer Steve Chawkins contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.