Studs Terkel, writer and radio personality, dies at 96

- Share via

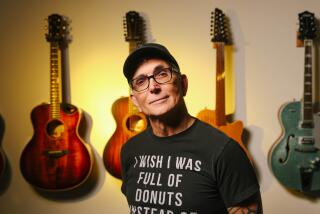

Studs Terkel, who made his name listening to ordinary folks talk about their ordinary lives -- and who turned that knack for conversation into a much-honored literary career -- died Friday. He was 96.

Terkel died of old age at his home in Chicago, his son Dan said.

“He lived a long, eventful, satisfying, though sometimes tempestuous life,” Dan Terkell said. “I think that pretty well sums it up.”

The author of blockbuster oral histories on World War II, the Great Depression and contemporary attitudes toward work, Terkel roamed the country engaging an astounding cross-section of Americans in tape-recorded chats -- about their dreams, their fears, their chewing gum, about racism, courage, dirty floors and the Beatles.

With his loud laugh and raspy voice, plus his inept fumbles with his tape recorder, he set his subjects at ease and tugged from them memories, predictions and simple truths about their everyday existence. Terkel transcribed and edited the interviews, then compiled them into books that were at once intimate and sweeping, among them “Division Street,” “Hard Times,” “Working,” and “The Good War,” which won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction.

Terkel was also a legendary radio personality, hosting a daily music and interview show on Chicago’s WFMT for 45 years.

He never prepared his questions. He interrupted his guests often. Yet Terkel was known as a master interviewer, able to establish an easy rapport with just about anyone. His secret, he once said, was simple: “It’s listening.”

And listen he did: to sultry jazz singers and insecure housewives; to a repentant Ku Klux Klan leader; to Bob Dylan, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Marlene Dietrich, Bertrand Russell; to a parking lot attendant and a lesbian grandmother; to a piano tuner; and to a barber.

As the late CBS newsman Charles Kuralt once said: “When Studs Terkel listens, everybody talks.”

Reviewers called Terkel’s oral histories accessible, powerful and deeply moving. “Readers will experience emotions they didn’t know they had,” the Cleveland Plain Dealer wrote of his World War II book. Though they were lengthy -- some more than 600 pages -- most of Terkel’s books shot straight to the bestseller list and much of his work was translated for publication abroad.

“I think he was the most extraordinary social observer this country has produced,” said Dr. Robert Coles, a Harvard professor of psychiatry who considered Terkel a friend and inspiration.

Though Terkel did interview the rich and famous, “he recognized the need to pay attention to the poor, the vulnerable, the ordinary people,” Coles said. “I pray for the day when American universities will understand that Studs Terkel is worth many departments of sociology. He’s an institution in himself.”

Louis “Studs” Terkel was born May 16, 1912, in New York City. His family moved to Chicago when he was a boy, and he quickly grew to love the city.

“It’s not that Chicago is that great,” he once said. “In fact, it’s horrible. But living here is like being married to a woman with a broken nose. There may be lovelier lovelies, but never a lovely so real.”

Real was what Terkel always wanted to get at: real people, real lives and real emotions.

He did not claim to be a social scientist. He did not seek to conduct a statistically valid poll. He simply talked to people he found interesting. He didn’t hide his liberal politics, and at times his cross-sections seemed tilted heavily to the left. In general, though, Terkel sought to reach across lines of politics, race, class, education and geography to coax America’s history from its varied voices.

“ ‘Statistics’ become persons, each one unique,” he once wrote. “I am constantly astonished.”

Terkel developed his taste for gabbing as a child hanging out with the blue-collar workers who lived in his family’s Chicago rooming house. The men would get drunk on a Saturday night and talk to young Terkel for hours.

His father, a tailor, died when Terkel was 19. His mother, Anna, was able to put him through the University of Chicago for an undergraduate and a law school education. Yet Terkel graduated disillusioned with the law. So he worked for a time as a federal statistician. He acted in radio soap operas (usually playing a gangster, with lines of “stunning banality,” he recalled).

Finally, in the 1940s, he moved into radio full time, first as a newscaster, then as a disc jockey and variety-show host on Chicago’s WFMT. By this time, he had thrown off his given name in favor of Studs -- a tribute to the fictional Studs Lonigan, a rough and ready-for-anything character created by novelist James T. Farrell.

Well on his way to becoming a Chicago institution, Terkel expanded into television in 1949 with “Studs’ Place.” An informal mix of banter and jazz, the show was set in a restaurant. “It was kind of like a ‘Cheers.’ But better,” Terkel said years later.

The breezy but smart informality of his programs won Terkel a devoted audience on radio and TV.

“Studs’ Place” ran from 1949 to 1953 -- and was only canceled, Terkel later maintained, because he was blacklisted by Sen. Joseph McCarthy for his liberal leanings. (He supported causes like rent control, desegregation and the abolition of the poll tax. “In those days, it was all quite radical,” he recalled.)

Throughout the 1950s and ‘60s, Terkel continued to broadcast his radio interviews while writing newspaper columns, acting in Chicago theaters and even penning plays of his own.

He hit upon oral history as an outlet for his insatiable curiosity in 1967, when at the age of 55 he published “Division Street: America” -- a series of conversations about race with Chicago residents. The New York Times praised the book as “a modern morality play, a drama with as many conflicts as life itself.”

Terkel had himself a new career.

Blending journalism, history, sociology and literature, Terkel traipsed across the country, tape recorder at the ready, for the next 3 1/2 decades.

“I tape, therefore I am,” Terkel used to say. “Only one other man has used the tape recorder with as much fervor as I -- Richard Nixon.”

Terkel’s techniques came in for some criticism, especially after “The Good War” won a Pulitzer Prize. Some called his work overly sentimental. Others accused him of letting his liberal politics taint his selection of interview subjects and his editing of conversations. Still others wondered aloud how Terkel could be considered a master author when he did little more than transcribe other people’s memories.

In response, Terkel said he had but one goal for each of his books: to open new worlds for his readers. He wanted them to feel what it was like to be a laid-off factory hand during the Depression. Or a soldier facing his first enemy fire. Or a black businessman, or a poor Latino. Or a Miss USA.

“If I can get that in a book,” Terkel said, “that’s what it’s all about.”

Thus, in “Hard Times,” he probed the guilt many senior citizens felt for having survived the Great Depression. In “Working,” he let Americans vent about their jobs -- and found a depressing majority saw themselves as automatons. In “The Good War,” he got his subjects to discuss racism, officers shot in the back by their own troops, and other topics that mainstream historians had shied away from.

“No one has done more to expand the American library of voices,” President Clinton said upon awarding Terkel a National Humanities Medal in 1997.

“People would say the truth to him even when they had lied to themselves for their [whole] lives,” Terkel’s longtime editor, Andre Schiffrin, added. “The key thing was his respect for them. He wasn’t there to use them. He wasn’t there to make a point. He really wanted to hear what they had to say, and he respected them.”

Terkel, his editor added, was “a true democrat.”

Editing his interviews into book-ready segments took great discipline; often, Terkel had room for less than 10% of his material. Exchanging draft after draft with Schiffrin -- who published all his books at New Press -- Terkel would struggle to distill an evening’s conversation into an essential, honest portrait of just five or six pages.

In his later years, Terkel returned to his original tapes to mine material for new books -- and to catalog reel after reel in the Chicago Historical Society archive. (The society has put excerpts from those interviews online at www.studsterkel.org.) The exercise was his way of combating what he described as “national Alzheimer’s disease” -- the rush-rush, live for the minute pace he deplored as irreverent and dangerous.

“We don’t remember anything. There’s no yesterday in this country,” he often complained. “I want to re-create those yesterdays.”

Despite his passion for the past, Terkel didn’t live in it; he kept a hectic schedule of travel, interviews and writing even after signing off from his daily radio show on Jan. 1, 1988. That same year he appeared in “Eight Men Out,” a film about the Black Sox scandal of 1919, in the role of a savvy newspaperman.

In 1996, Terkel had quintuple bypass surgery -- and emerged hale as ever, still dedicated to his daily routine of two martinis, two cigars, and too many hours at the electric typewriter. His book of interviews about death and dying, “Hope Dies Last,” was released in 2004, when he was 92.

In 2005, at the age of 93, Terkel had another round of open-heart surgery, which doctors described as terribly risky for a man his age. He was back at work within weeks, promoting his 16th book, “And They All Sang,” an eclectic collection of interviews from his half-century on the radio.

When officials from Rutgers University knocked on Terkel’s door in May 2007 to present him with the Stephen E. Ambrose Oral History Award, they could hear furious typing inside. At the age of 95, he was polishing his memoir, “Touch and Go,” published in 2007.

Though he was nearly deaf by then, Terkel’s memory for names, dates and bawdy anecdotes was impeccable.

Dressed in his trademark red and white checked shirt and red socks, Terkel would entertain visitors at his Chicago home with long rants against President Bush. His monologues were sprinkled with an array of allusions: He’d quote Shakespeare and Henry Kissinger and “Ode on a Grecian Urn” -- and then, moments later, delve into the details of the 1920s Teapot Dome scandal.

Though rarely given to introspection, Terkel did tell one interviewer that he felt he had shortchanged his family by being so absorbed in his work. His wife of 60 years, Ida, died in 1999. He is survived by their son, Dan, who altered the spelling of his last name to Terkell.

Terkel planned his funeral years ago.

He wanted readings from Mark Twain and George Bernard Shaw; music from Schubert and Mississippi bluesman Big Bill Broonzy. He wanted his ashes -- and Ida’s -- to be scattered in the Chicago square where, as a young man, he stood on a soapbox and shouted out his leftist views.

And Studs Terkel wanted this as his epitaph: “Curiosity did not kill this cat.”

Simon is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.