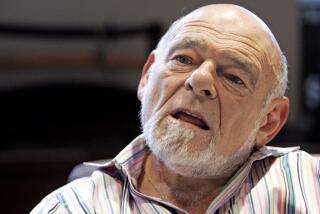

John Van de Kamp, former California attorney general and L.A. County district attorney, dies at 81

- Share via

John and Andrea Van de Kamp had been married almost a decade when they went to the Kentucky Derby in 1986.

By that point, Van de Kamp was already a career politician and had garnered a reputation for being cautious — friends and colleagues saw a measured but thoughtful leader who would routinely defend laws he personally opposed, because it was his job to do so.

But at Churchill Downs, Van de Kamp and a friend split a $100 bet on a 17-to-1 longshot.

When the horse won, Van de Kamp’s wife was introduced to a side of her husband she didn’t know. “I’d never heard him yell before,” she said. “… I heard words that I didn’t know he knew. I must say, he was quite articulate with them.”

A towering political figure who became the top prosecutor in Los Angeles County and then California before running for governor, Van de Kamp died Tuesday at his home in Pasadena after a brief illness. He was 81. A family friend, Fred Registrar, confirmed his death.

One election cycle after that spring afternoon at the racetrack, opponents would accuse Van de Kamp of being too dull and robotic to take the reins of governor of California . The criticisms would ultimately help sink the Southland native in the 1990 Democratic primary against Dianne Feinstein, and he would never again seek high-profile political office.

But by that time, the modestly raised member of a family known for its baked goods and windmill-themed bakeries had already left a significant mark in public life. In a career that spanned decades, Van de Kamp helped institute a revolutionary computerized fingerprint identification program, was instrumental in the push to “fast track” cases stuck in the state’s civil courts, and pressed a laundry list of environmental, consumer rights and campaign finance reform cases that chiseled his public image into that of a liberal lion.

“John Van de Kamp lived for the values of justice and opportunity that define the state of California,” said state Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra, who once worked for Van de Kamp. “I will forever be grateful for the confidence he showed in me from my earliest days of public service under his leadership at the California Department of Justice.”

“John understood the higher calling of public service,” Becerra said. “He performed for the people of California like few others.”

Gov. Jerry Brown also praised the former attorney general.

“John was a wonderful public servant and had a real sense of justice,” Brown said in a statement released by his office.

Born in Pasadena to a bank teller and a teacher — and into a prominent family whose name was synonymous with baked goods — Van de Kamp attended a private school in Altadena, which thrust him into the outdoors and fostered in him an early appreciation for nature.

By 16, the precocious student went away to Dartmouth, and after a brief foray into broadcasting, he graduated from Stanford Law School in his early 20s. He served a short stint in the military before being appointed an assistant U.S. attorney.

He eventually entered politics, making an unsuccessful bid for a San Fernando Valley congressional seat, and continued working on campaigns until 1971, when he was tapped to head L.A.’s new Federal Public Defender’s Office. The job required him to switch sides, sometimes standing up to the very agencies he had once fought for.

Five years later, he would reverse roles again, after being selected to replace L.A. County’s district attorney, who had died in office.

“An extraordinary leader of impeccable integrity, John never backed away from taking strong, principled stands on tough issues,” Los Angeles City Atty. Mike Feuer recalled. “John was supremely effective at everything he did — always with a quiet confidence and devotion to public service that inspired generations of lawyers.”

It was in this role that Van de Kamp came face to face with the infamous Hillside Stranglers case, which would blotch his public career.

In 1977 and 1978, 10 young women and girls had been strangled, their bodies dumped on hillsides near downtown Los Angeles. Four years later, Van de Kamp, as district attorney, had to decide whether to prosecute one of the accused killers.

One suspect, Kenneth Bianchi, had accepted responsibility for five killings in a plea bargain that spared him the death penalty. He also agreed to be the key witness against his accomplice and cousin, Angelo Buono Jr.

But Bianchi began changing his story to investigators, and doubt emerged about his reliability as a witness. Ultimately, senior prosecutors recommended dropping the murder charges against Buono and instead prosecuting him on lesser sex crimes. Van de Kamp approved the plan.

Then, in a bold and unusual move, Superior Court Judge Ronald George ordered the capital case to continue. It was transferred to then-Atty. Gen. George Deukmejian, whose office eventually secured Buono’s conviction for nine of 10 murders.

“We made an error in that case,” Van de Kamp told The Times later, during his bid for governor. “And I take full responsibility.”

Despite the setback, Van de Kamp easily won election to the state attorney general’s office, where he created special units to handle child abuse, sexual assault and police shootings. It was there he launched the Cal-ID fingerprint system and, in an uncharacteristically brash move, strode into the Legislature with an AK-47 to support an effort to limit private ownership of assault weapons.

But the job of being the state’s top prosecutor would expose him to new problems that would eventually hamstring his campaign for governor. In his role as attorney general, for example, he felt compelled to defend the state’s efforts to prohibit the use of Medi-Cal benefits for abortions — though he disagreed with the law.

It proved to be one of many contradictions. Indeed, as he campaigned against Feinstein, a somewhat confounding portrait of the longtime politician emerged: a Roman Catholic who supported a woman’s right to choose; an opponent of the death penalty who touted sending inmates to death row; a lifelong political insider who campaigned on “draining the ethical swamp” of Sacramento special interests.

Feinstein won the race, though she went on to lose to eventual Gov. Pete Wilson. Van de Kamp, meanwhile, came back home, serving as president of the State Bar of California, representing the thoroughbred owners of California and becoming a special monitor in beaten-down Vernon.

“He exemplified all that is best about public service,” said Harvey Rosenfield, founder of the advocacy group Consumer Watchdog. “He was a determined advocate but always gracious and thoughtful. John represented a golden era of politics, when the public’s interest was always the priority over partisan gain.”

Van de Kamp is survived by his wife and a daughter, Diana.

Times staff writer Patrick McGreevy contributed to this report.

UPDATES:

6:15 p.m.: This article was updated throughout with more biographical information and reaction.

This article was originally published at 12:35 p.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.