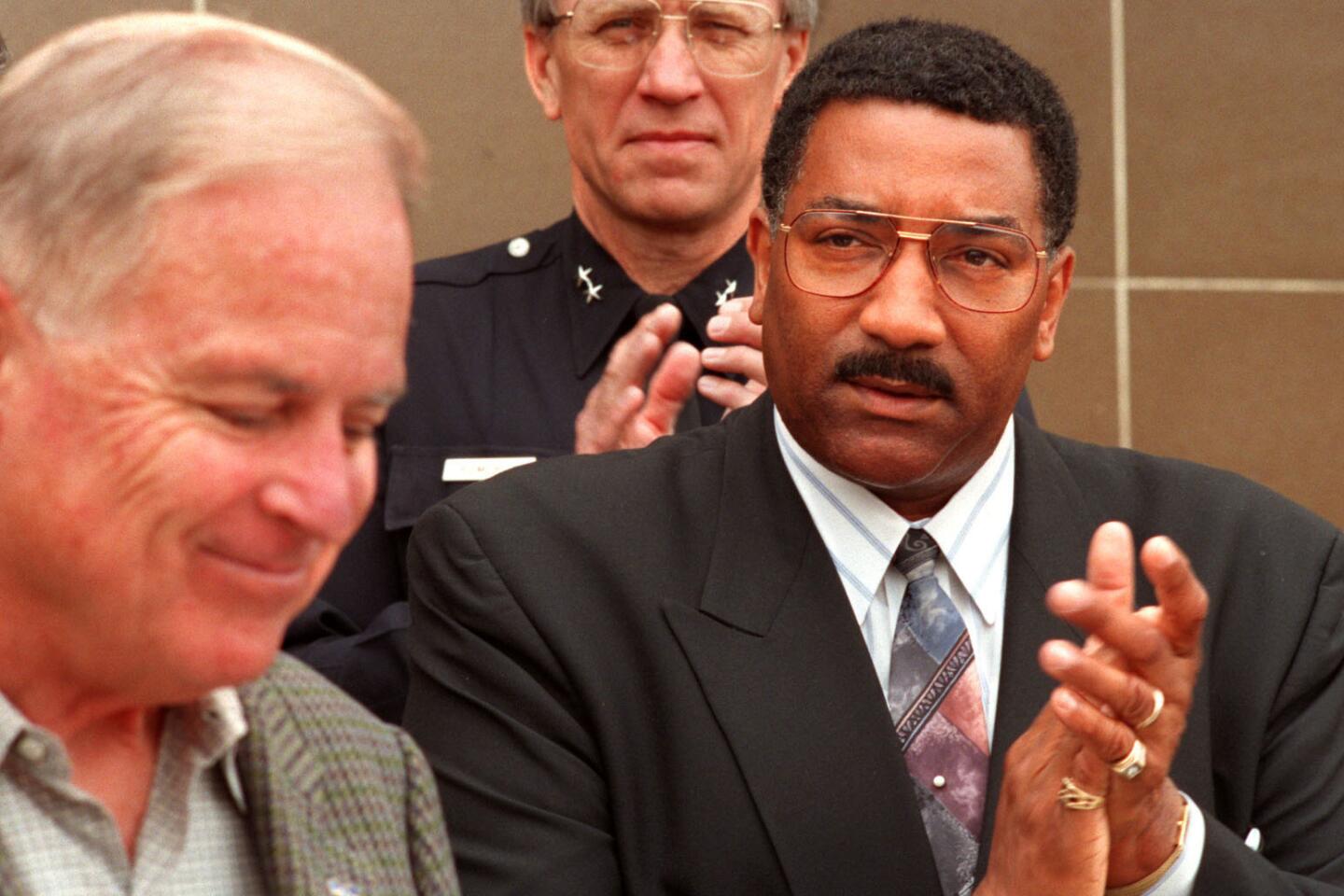

From the Archives: LAPD chief Willie Williams reflects on reforms and roadblocks: ‘I was the guinea pig’

Los Angeles Police Chief Willie L. Williams during a May 16, 1997, farewell interview in his office.

- Share via

A sometimes contemplative, sometimes bitter Police Chief Willie L. Williams reflected Thursday on his five-year term at the helm of the Los Angeles Police Department, crediting himself with implementing important reforms, while also complaining that he was a “guinea pig” confronted with daily attempts by political leaders to meddle in departmental affairs.

“Politics has greatly intruded, for the right or the wrong reasons, into the day-to-day management activities of the Los Angeles Police Department,” Williams said in an interview with The Times. “I don’t think it takes a brain surgeon to see that.”

Williams, who for years has hailed the reform measures passed by voters in 1992, registered his first public criticism of those changes, suggesting that they had passed too much power to politicians and stripped the LAPD of its independence. The result, said the outgoing chief: a police agency beset by the competing agendas of 15 City Council members, five police commissioners and the mayor.

“I’m just not sure today if it’s what the public wants or what the public intended when they changed the charter in 1992,” said the chief, whose bid for a second term ended unsuccessfully amid complaints about his honesty and his capabilities as a manager. “I think the public wanted accountability to the civilian structure, but I don’t know that they wanted the 21 bosses getting involved in the day-to-day managerial issues of the department.”

For Williams, Thursday--his last day at the office--was one of farewells. He spent much of the day hosting open houses and saying goodbye to LAPD employees, more than 500 of whom lined the halls outside his office waiting for a chance to shake his hand and have their pictures taken with him. He posed for a group photograph with the department’s top brass on the front lawn of Parker Center, and he met with Police Commission President Raymond C. Fisher, head of the panel that unanimously voted in March to deny the chief a second five-year term.

Afterward, Fisher described the session as a “graceful goodbye.”

“I expressed my appreciation for what he had done for the city,” the commission president said. “I told him I knew it had been a painful process for both of us, but I said I thought he handled himself with professionalism and dignity.”

Williams’ last official day as chief is Saturday, when he will participate in the LAPD’s annual celebrity golf tournament. After that, Assistant Chief Bayan Lewis will take the reins until a permanent successor is chosen.

Rebuilding Public Support

In his interview with The Times, Williams listed a number of accomplishments, most notably his work to infuse the LAPD with the law enforcement philosophy known as community-based policing, his push to diversify the ranks and his success at rebuilding public support for the LAPD.

Politics has greatly intruded, for the right or the wrong reasons, into the day-to-day management activities of the Los Angeles Police Department.

— Willie Williams

“It takes a long time to achieve perfection, and we’re not there yet,” Williams said of his moves to bring women and minorities into the LAPD and to promote them into its upper ranks. “But for the first time there’s no doubt where the chief stands on these issues, and we’ve begun to make significant strides.”

Even Williams’ critics credit him with those gains, particularly in the area of restoring public confidence in the LAPD.

When Williams came to Los Angeles in 1992, confidence in the Police Department had been badly rattled, first by the 1991 beating of Rodney G. King and then by the department’s response to the riots the next year. Williams launched an ambitious community-outreach effort, and within two years, the department’s public approval ratings had climbed, along with the chief’s, to more than 60%.

As he described his achievements, Williams appeared relaxed Thursday. Dressed in civilian clothes, a gray suit and pale yellow shirt, he smiled occasionally, leaning back in his chair or gazing toward his office windows as he reflected.

When he turned to his tenure’s struggles, however, the outgoing chief spoke more quickly and with obvious anger.

“In a sense, I was the guinea pig,” Williams said, adding that he believes his successor will find it easier going because of the steps he already has taken. “It’s always nice when you can follow the trailblazer.”

Williams did not criticize Mayor Richard Riordan by name. But he pointedly passed up several chances to praise the mayor and he broadly hinted at his unhappiness with the city’s chief executive.

Asked whether he supported Riordan, the chief answered: “He’s the elected mayor. He’s supposed to represent me and my family and everybody else who lives in Los Angeles.”

Asked whether he believes Riordan has served the LAPD well, Williams smiled thinly and responded: “He serves the city overall well. He got reelected.”

Finally, Williams acknowledged: “The mayor and I had some agreements at times, and we had some significant disagreements, but that’s life with the big guys in the big league.”

Riordan, whose displeasure with some aspects of the chief’s management is no secret, did not respond directly to Williams’ comments. Instead, he reiterated through a spokeswoman that he believes Williams did register important accomplishments during his time as the 50th LAPD chief.

“When the chief took office, there was a need for stronger relationships between the Police Department and the community,” Riordan said. “Chief Williams did a good job of building those relationships.”

Although both top officials danced around their differences Thursday, the chief made it clear that he and Riordan long had been at odds. Williams, for instance, characterized the mayor as overly concerned with adding police officers while failing to recognize the larger issues involved in Police Department expansion.

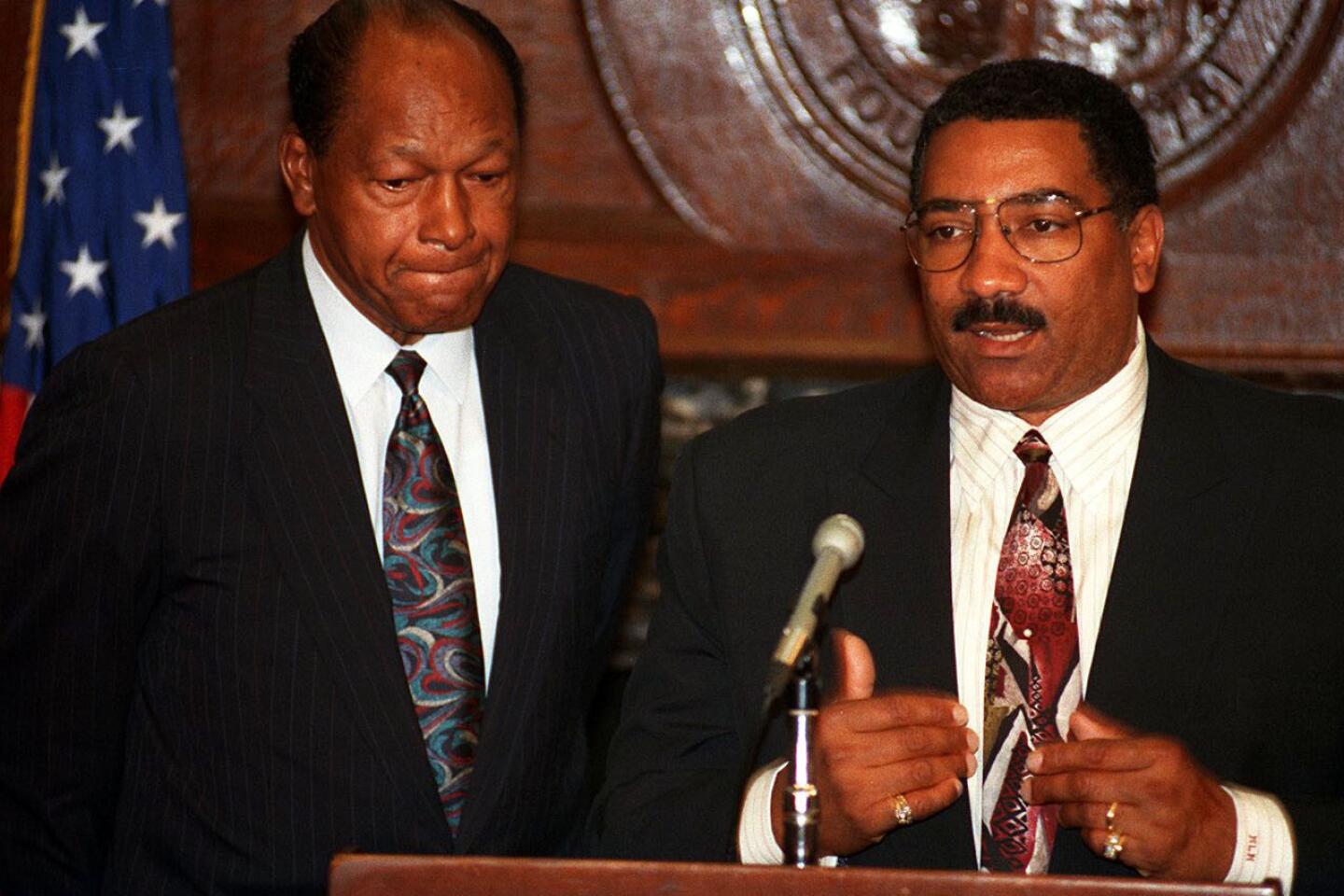

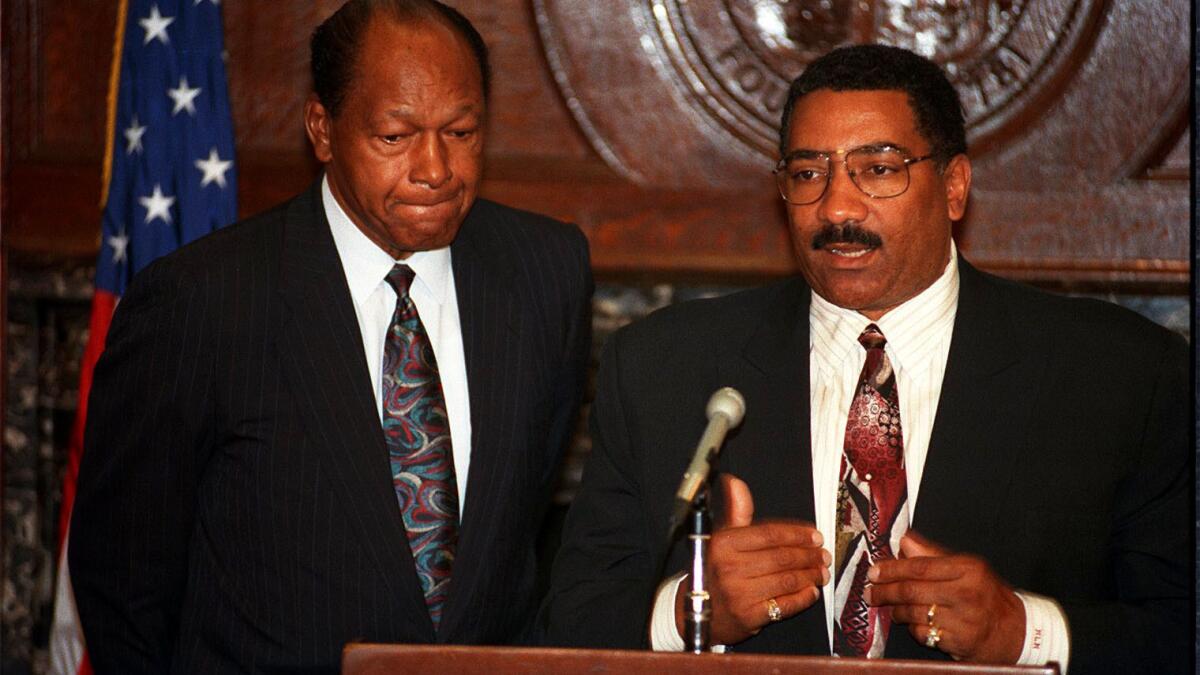

Los Angeles Police Chief Willie Williams answers questions about the city’s riot preparedness as Mayor Ton Bradley listens in 1993.

When he ran for mayor in 1993, Riordan pledged to expand the LAPD by 3,000 officers in four years, a promise that he asked Williams to carry out but that was not fulfilled.

“The challenge for me as chief in dealing with a brand-new mayor and staff who only wanted to see people in blue suits, perhaps, was that I wasn’t a brand-new chief,” said Williams, who was brought to Los Angeles from Philadelphia by then-Mayor Tom Bradley and his Police Commission, only to have all those leaders gone within a year, replaced by Riordan and his appointees.

“I knew that when you aggressively try to hire a net increase of 2,000 or 3,000, it requires supervisors, detectives. It requires cars, radios, civilians, overtime, new buildings. All those things go in there,” Williams said. “My job was to say so. It was interpreted that the chief was disagreeing with the mayor. No, I was doing what a chief of police was supposed to do. . . . It was my job to get it done.”

After initially registering concerns about Riordan’s expansion plans, Williams and his top staff joined the mayor’s office in drafting a hiring blueprint. That document became an albatross for the chief, in part because it did not fully take attrition into account. As a result, the LAPD was forced to play catch-up and to vastly step up hiring to make up for the officers who were leaving more quickly than anticipated.

For years, the department fell behind the plan goals, irritating Riordan and his aides. That was compounded further when the initial additions to the department were used to backfill vacancies rather than to expand patrol operations, as the mayor desired. Eventually, the department began to expand its street patrols, but only after substantial goading from the mayor and his appointees.

What’s more, the intense emphasis on expansion troubled many reform advocates, who worried that the department was losing its emphasis on internal improvements, especially the reform blueprint drafted by the Christopher Commission in 1991. Thursday, Williams insisted that he had consistently lobbied for reforms despite the competing pressures to put more officers on the street.

Christopher Reforms Criticized

At the same time, the chief registered surprising dissatisfaction with the Christopher Commission report, a document that largely was responsible for Williams ending up with the LAPD chief’s job. It was the Christopher Commission that urged former Chief Daryl F. Gates to step down, eventually creating the vacancy that Williams filled.

But the commission recommendations approved by voters in 1992 also limited the chief to two five-year terms and gave the Police Commission broad power to decide whether a chief deserved reappointment. It was that process that the commission exercised in March when it voted against giving Williams a second term.

In the interview, Williams said it may be time to look again at some of the Christopher Commission recommendations.

“It was just a report with recommendations,” Williams said. “It wasn’t a Bible.”

In the years since the report concluded that racism and excessive use of force were widespread issues in the LAPD and warranted sweeping management changes, the situation facing Los Angeles police has shifted, Williams said.

“The public’s wants and expectations have changed,” he said. “The guiding principles and philosophy are still there, and should be followed. But you certainly have to take a look and say, ‘Is it as necessary to do certain things today as it was in 1991?’ ”

Although the issues of LAPD expansion and reform were the mainstays of Williams’ administration, his closing months in office were marked by his increasingly fractious relationship with City Hall. Williams had several times been accused of lying, most notably in the investigation of charges that he received free accommodations in Las Vegas, but also in a series of other issues such as his position on a lawsuit facing the city, a proposal to modify the work schedule of police officers and a statement he made regarding the LAPD monitoring potentially problem officers.

Those issues, combined with growing questions about his effectiveness as a manager, left Williams increasingly defensive as he launched his bid for reappointment.

Then, when the Police Commission set out to evaluate his performance over the past five years, Williams’ lawyers launched a series of broadsides against the panel and its right to consider the chief’s continued tenure. They threatened lawsuits and accused Riordan and other officials of mistreating Williams.

As the tension surrounding the issue mounted, some officials drew comparisons to the closing days of Daryl Gates’ administration, when Gates and his Police Commission bosses fell into open combat.

Both Williams and Gates reject that comparison, and Williams said Thursday that he does not regret having gone to bat for his job, even though he realizes that it angered some city leaders.

“Let me tell you something,” Williams said, his eyes narrowing and his pace quickening. “When you’re a chief of police, when you’re a leader, you have to do what you think is right. . . . Willie Williams would not be able to look in the mirror, look at his family, look at his children, look at his friends and neighbors, look at people in this department if I just packed up my bags and went away when someone says, ‘Chief, we don’t like what you’re doing. Get out of town.’ I didn’t walk into Los Angeles to be tossed out of town, and I wasn’t going to be tossed out without expressing my concerns.”

Police Officer Career Over

The decision on a permanent successor to Williams is expected sometime in August. The Police Commission will choose three top finalists and forward their names to Riordan for him to consider. The mayor can pick one of the three or, if he is not satisfied with those choices, ask for more candidates to evaluate.

At the moment, speculation centers around Deputy Chief Mark Kroeker, who heads operations in the South Bureau, and Deputy Chief Bernard Parks, who supervises the Bureau of Special Investigations. Neither has been a Williams favorite: Kroeker is the only senior officer at the LAPD never to have received a promotion from Chief Williams, and Parks is the only top-ranking one to have been demoted by him. Deputy Chief David J. Gascon also is considered a potential successor, and a few possible candidates outside the LAPD have surfaced as well.

Williams declined Thursday to discuss whom he would favor for the permanent job, beyond saying he expects the next chief to come from inside the LAPD.

Although Williams said he hopes to find work as a consultant after leaving the department--and added that he is considering writing a book and giving speeches--he stressed that his career as a police officer is over.

And despite the controversies and disagreements, the earthquakes, fires and political infighting, Williams said he will retire without regret.

“That’s part of being a leader in an organization,” he said. “Each person takes it as far as you can, and then the next person comes in and takes it to the next step. I think . . . history is going to say that the Williams administration made major, long-lasting changes in LAPD, not just short-lived ones.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.