For better or worse, John Updike produced a nearly endless stream of work

- Share via

For David Foster Wallace, he was one of “the Great Male Narcissists.” Martin Amis declared that the last section of his 1989 memoir “Self-Consciousness” was “to my knowledge the best thing yet written on what it is like to get older: age, and the only end of age.” Nicholson Baker celebrated his “assured touch, [his] adjectival resourcefulness.”

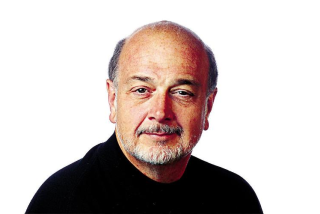

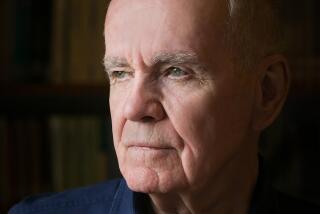

But for me, the lasting image of John Updike, who died Tuesday of lung cancer at age 76, is as a self-described “freelancer,” who produced a nearly endless stream of book reviews, novels, stories, poems and occasional pieces -- more than 60 volumes’ worth in all -- because he felt he’d be forgotten if he didn’t keep his name in print.

I met Updike in November, when I did a public interview with him at UCLA Live. He had been sick, he said, with pneumonia. He looked thin, but he was hearty, dressed in a suit and a pink tie. Before the event, we sat in the green room at Royce Hall and talked baseball, going back and forth about the Yankees (my team) and the Red Sox (his), as well as the Philadelphia Phillies, who had won the World Series a few weeks before.

It’s easy to forget, amid all his writing, that one of Updike’s early masterpieces was a 1960 essay for the New Yorker called “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” in which he describes Ted Williams’ final game, a spectacle he almost effortlessly elevated to the level of art. “The affair between Boston and Ted Williams,” Updike wrote, “has been no mere summer romance; it has been a marriage, composed of spats, mutual disappointments, and, toward the end, a mellowing hoard of shared memories. It falls into three stages, which may be termed Youth, Maturity, and Age; or Thesis, Antithesis, and Synthesis; or Jason, Achilles, and Nestor.”

This was Updike’s gift: the felicitous phrase, the attention to detail, the ability to make the mundane profound. And yet, this was also his greatest limitation, for in his lesser efforts, he never quite penetrated the surface of his language, leaving us to skitter along the exterior without breaking through to the emotions underneath.

To my surprise, Updike was very open about this; he brought it up, once we were onstage. Did he write too much? he asked rhetorically. Probably. But he had made a promise to himself early on that he would publish a book a year, and a novel every other year, and he saw no reason to rethink it now.

Had he written some books that hadn’t worked? Certainly. What writer of his longevity hadn’t, on occasion, missed the mark? But better that, he suggested, than to hole up, a la Saul Bellow, and only deliver a piece of writing every five years. Think of the anxiety to deliver, the pressure to produce a masterwork. It was far more useful, he had decided, to be front and center in the culture, to be a working writer, to do the best he could and then move on.

Updike is commonly regarded as the poet laureate of the suburbs, but that’s not really accurate. Yes, he evoked a certain middle-class domestic culture at the precise moment (the 1960s and 1970s) that it was exploding; without him, there’d be no Rick Moody, no Ethan Canin -- to name just two.

But more than suburban life, Updike was really an explorer of consciousness, of the mental drama; this is why Wallace derided him as a solipsist. Even his most celebrated works, the Rabbit novels, are less about domestic life than they are sagas of one man -- confused, guilt-ridden, tormented by his own not-fully-thought-out choices -- struggling to make sense of himself. For Updike, it didn’t happen unless he’d thought it through, reflected on it. If that, at times, could keep us at a distance, it was the clearest expression of who he was.

This is why, of all his contemporaries, Updike was the most effective critic; for more than 40 years, he reviewed books and art for the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books with acuity and grace. He described it as a way to keep his hand in, but in fact, criticism became a parallel spoke of his career, a balance to his fiction, a way to think about, as well as to produce, literature.

Clearly, the two pursuits spoke to each other within him; “Rabbit, Run” -- published in 1960, when he was just 28 -- was written in reaction to another iconic novel of its moment, Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road.” What Updike wanted, he explained on that night at UCLA, was to write a book in which going on the road had consequences, to explore what might have happened had Kerouac’s Sal Paradise left a wife and child behind.

Such a statement speaks to a certain rigid moral vision, which was again, perhaps, both a weakness and a strength. Updike was not a revolutionary writer, and he may have suffered from having lived -- and written -- through revolutionary times. His least compelling books, such as 2006’s “Terrorist,” are attempts to remain relevant; he was at his finest when he described the world he saw.

But that, too, is the legacy of the working writer, which Updike was until the end.

Ulin is book editor of The Times.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.