Touches of home help Venice clinic put young patients at ease

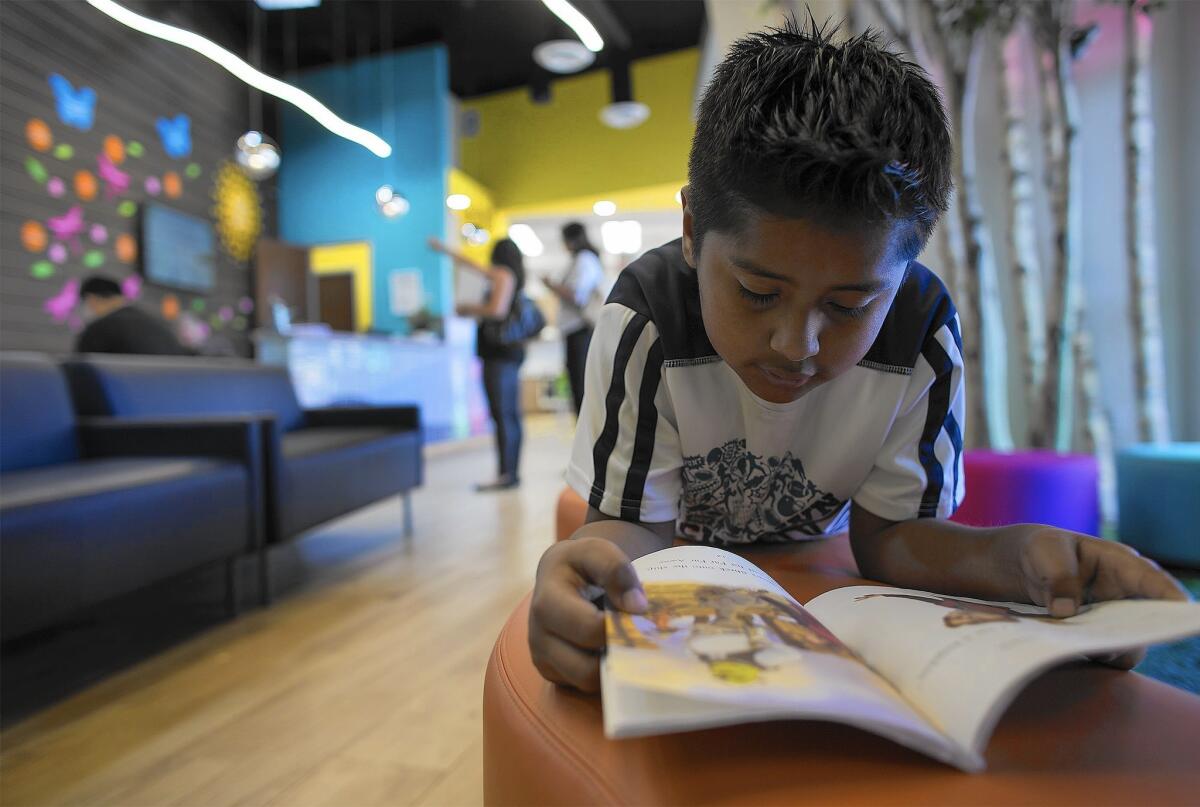

Fernando Hernandez, 8, of Los Angeles, reads a book while waiting for his doctor appointment at the new Lou Colen Children’s Health & Wellness Center.

- Share via

When Yana Barba stepped into the Venice Family Clinic’s new children’s health center this month, what she found was not a typical doctor’s waiting room.

It smelled of cinnamon from the sweet potatoes a staff member was pulling out of an oven in the corner. A child squealed with glee as he played with a toy gorilla and stomped his feet on a carpet of artificial grass.

Barba’s 5-year-old daughter Marissa ran over to a huge digital whiteboard and began drawing on it with her finger. Another woman and her toddler had sunk into a couch to read a book.

Barba, who is nine months pregnant, has to come in for a visit every two weeks for prenatal care. It’s easy to bring her daughter along, she said, since there are so many ways to entertain kids here. “I don’t even think they know they’re at a doctor’s office,” said Barba, 40.

The Lou Colen Children’s Health and Wellness Center is part of a network of free clinics that have historically served uninsured patients in Los Angeles County. Though this branch — which opened in Del Rey last month — still treats many low-income families, its patient-friendly design and services reflect a shift in the way clinics across the nation are delivering healthcare.

For poor families, such health centers were often seen as drab places of last resort, said Giovanna Giuliani, associate director for California HealthCare Foundation‘s Improving Access team.

But now, clinics are trying to brighten that reputation.

Along with a waiting room kitchen where staff members offer free cooking demonstrations, the new Venice Family clinic has shelves of books for kids to take home after each visit. There’s a toy forest to play in, with life-size trees made of steel and covered with synthetic bark and painted to appear lifelike.

NEWSLETTER: Get essential California headlines delivered daily >>

With the health insurance expansion under the Affordable Care Act, newly insured patients have options for the first time beyond free clinics. That’s led clinic administrators to think about ways to make themselves more appealing to patients, so those they’ve treated free for years will continue to visit now that they have insurance.

Before the Affordable Care Act went into effect last year, 65% of Venice Family clinic patients were uninsured. Now, 55% can pay for their care through Medi-Cal, the state’s health program for the poor that was expanded under the law.

“That’s momentous. That’s the first time it’s swung the other way,” said Laney Kapgan, the clinic’s chief development officer. The clinic, which is an affiliate of UCLA, covers the cost of uninsured patients with the help of grants and funding from L.A. County.

Venice Family Clinic Chief Executive Elizabeth Benson Forer said she and her colleagues spent two years determining the best way to design the new clinic so it would be a resource that families would want to visit.

They opted to put couches in the waiting room instead of the typical hard-backed chairs so sick kids could nuzzle up against their parents. They also built extra-large exam rooms after noticing that families often visit the clinic in big groups.

To brainstorm ideas for designing the new clinic, administrators also enlisted the help of students from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena.

Alaina Mickes, a student who worked on the project, said that she tried to keep in mind the question “What does it look like to the child, and what does it look like to the adults?”

So kids would enjoy their visits, they gave each treatment room a forest, ocean or galaxy motif and installed furniture with shelving to hold baskets of toys.

In the waiting room, Mickes said she wanted to create an area where kids could feel like they were outdoors. Low-income kids living in the area around the urban clinic struggle with obesity and staying active.

Administrators also designed the clinic so it could function as a “patient-centered medical home,” a place where patients feel comfortable returning for treatment by providers who know them and their medical histories. A concept pushed by the Affordable Care Act, such medical homes also allow providers to track patients’ treatment and deliver the best care possible as a team.

To encourage such staff collaboration, the clinic abandoned the idea of separate offices for doctors and nurses, and instead built one big room in the back for all workers.

“What it’s trying to accomplish is more holistic care for the patient, so that when you go into the clinic, you know who’s taking care of you,” said Giuliani of the California HealthCare Foundation.

Follow @skarlamangla on Twitter for more L.A. health news.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.