The president was polarizing, even crude. The shocking became routine. Somehow, we survived 1968 — or did we?

- Share via

The year was fading. It was the morning of Christmas Eve, 1968, and the three-member crew of Apollo 8 was on its fourth orbit of the moon — the fourth such orbit in human history. Following their flight plan, the astronauts were executing a 180-degree roll, slowly turning the capsule as it shot through space.

“Oh my God!”

Astronaut Bill Anders had been peering out a side window, holding up a bulky Hasselblad camera to take photographs of the moon’s cratered surface. Looking up at the lunar horizon, he glimpsed something that no one had seen before: an Earthrise.

“Here’s the Earth comin’ up,” he said, a trace of wonder in his voice. “Wow, is it pretty!”

Down there, on that gorgeous blue orb, it had been a hell of a year. The Vietnam War was raging, and Americans were fighting one another in the streets of their own cities. Half the world was engulfed in protest; angry students nearly shut down France and were slaughtered in Mexico. The Cultural Revolution swept like a fury across China; the Soviet Union crushed the Prague Spring. Assassins claimed the lives of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy; a beleaguered President Lyndon Johnson declined to run for reelection. Now Richard Nixon was weeks away from inauguration.

It all looked so peaceful, from the moon.

Anders snapped a black and white photo, then hollered to Jim Lovell. “You got a color film, Jim? Hand me a roll of color, quick, would you?… Hurry!”

Here’s the Earth comin’ up. Wow, is it pretty!”

— Astronaut Bill Anders

The photograph that Anders took became one of the most celebrated ever. It showed the Earth in all its living glory. It invited people to step away from one of the most contentious years anyone could remember and gain some perspective. Many talked about how it seemed to show the beauty and fragility of their one and only world, spinning through a dark and indifferent universe. The picture was credited with helping to launch the environmental movement.

But maybe it was Anders’ next words that said the most — about hoping to capture a perfect image for his camera on the next orbit. “It’ll come up again — I think,” he told Lovell. He thought.

Because in 1968, who knew?

A lot has changed in 50 years. The internet and cellphones have transformed the way we communicate. Our politics have become coarser and more polarized. Progress, however halting, has been made in race relations, in upholding the rights of women and people of different gender identities. Climate change has fundamentally altered the planet.

RELATED | 1968: A timeline of anger, grief and change »

Yet the parallels between now and then are hard to ignore. In 1968, the United States was a deeply divided nation, whose president was viewed by many as crass and unbefitting his office. The United States was mired in a long war that many saw as pointless. White supremacists, rallying behind the presidential campaign of former Alabama Gov. George Wallace, appeared newly emboldened. Gun violence and rampant drug abuse had given rise to worries about the fundamental health of American society. Women, people of color and gays and lesbians were demanding equality and respect.

And each day seemed to bring a new shock.

The news cycle may have been slower then, but the news was not. Here are just a few of the events of that tumultuous year:

In January, North Korean patrol boats seized a U.S. Navy spy ship, the Pueblo, and its crew of 83, raising the prospect of war with the reclusive Communist state. Later that month, North Vietnam launched the Tet Offensive, a massive assault on U.S.-held bases and cities throughout South Vietnam that deeply shook the confidence of the American public over a war their leaders had told them they were winning.

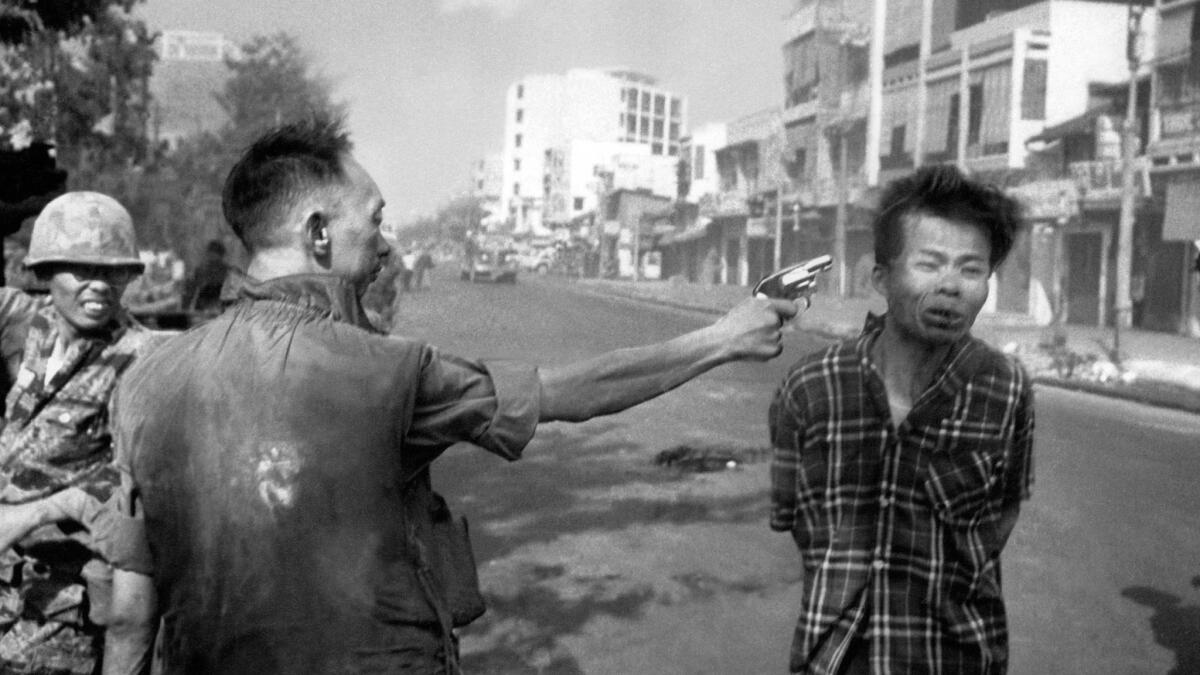

In February, Associated Press photographer Eddie Adams took a picture of South Vietnamese Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a Viet Cong prisoner on a Saigon street — a horrifying image that fed concerns that the United States was propping up a corrupt regime.

In March, Sen. Eugene McCarthy came within 230 votes of defeating Johnson in the New Hampshire Democratic primary. Four days later, Sen. Robert Kennedy, younger brother of the slain president, announced that he too would challenge the incumbent. At the end of the month, a weary Johnson delivered a long, nationally televised address, ostensibly about the Vietnam War.

RELATED | East L.A., 1968: The day a school walkout helped ignite the Chicano power movement »

Journalists talk about “burying the lead” — placing the most important news far down in an article. No one has ever buried the lead like Johnson, who concluded his speech with words that millions of Americans can recite to this day: “Accordingly, I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president.”

It was just four days later, on April 4, that King was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn. He was 39 years old. Kennedy got the word while campaigning in Indianapolis, and delivered the news to a shocked crowd — five decades later, it is still horrifying to hear their screams. His short, spontaneous speech would go down as one of the most eloquent in American politics.

It concluded: “Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world.”

Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world.”

— Robert F. Kennedy

Those words went unheeded. Within hours, riots erupted in 110 American cities, entire swaths of which were burned to the ground. The whole country seemed to be on fire. Had the American experiment failed?

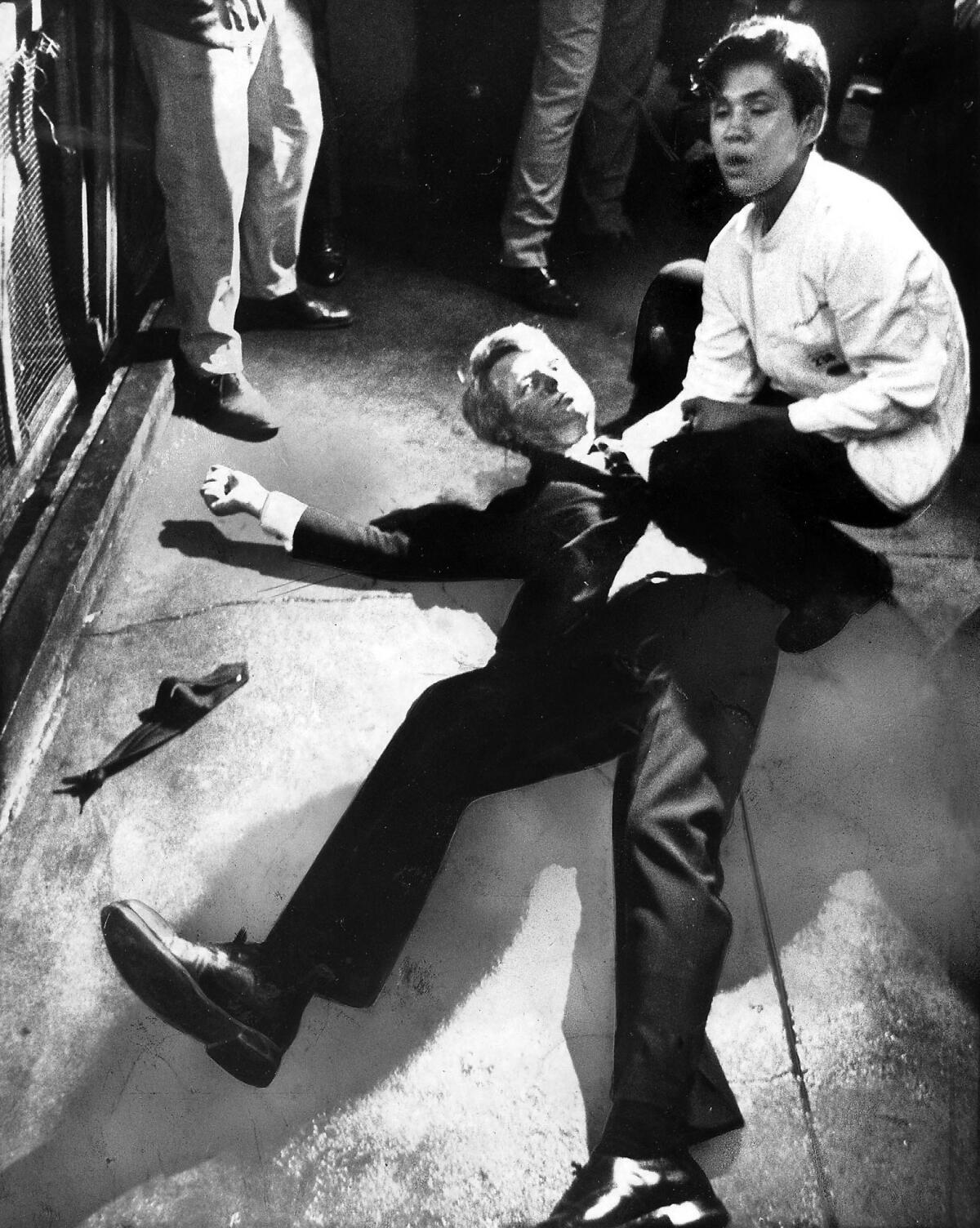

On June 4, Kennedy won the California Democratic primary, making him the odds-on favorite to become his party’s presidential nominee. A few minutes after midnight, he was shot to death at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles.

To millions of Americans, the back-to-back assassinations felt like the end of hope.

In August, at a heavily secured convention in Miami Beach, Republicans nominated Richard Nixon as their presidential candidate. Later that month, the Democrats convened in Chicago, where the streets quickly turned into a battle zone. “The whole world is watching!” antiwar demonstrators chanted as cops used their nightsticks to beat them brutally and cameras captured the mayhem for an international audience. The Democrats nominated Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey as their standard-bearer.

In October, the Summer Olympics were held in Mexico City, where, days earlier, police and soldiers had turned their guns on student protesters, killing or wounding hundreds. The Games would be remembered for this scene: African American athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith raising black-gloved fists from a medal podium as the national anthem played. It was a moment of singular power, reflecting both black pride and black anger.

In November, Nixon defeated Humphrey. In a victory speech, he pledged “an open administration” that would seek “to bridge the generation gap [and] the gap between the races. We want to bring America together."

On Dec. 21, Apollo 8 began its journey toward the moon.

On Christmas Eve, hours after the Earthrise photo was snapped, the three astronauts went on live television. Broadcast internationally, their appearance had an estimated audience of 1 billion people — at that point, the largest audience for any event in history.

Anders said the astronauts had a message for the world. He paused, and began to read from a King James Bible:

“In the beginning, God created the Heaven and the Earth. And the Earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters, and God said, ‘Let there be light.’ And there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good, and God divided the light from the darkness.”

He handed the Bible to Lovell, who read the next section of Genesis.

Mission Cmdr. Frank Borman concluded the cosmic broadcast. “And from the crew of Apollo 8,” he said, “we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas and God bless all of you — all of you on the good Earth.”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.