‘El Chapo’ prosecutors may have ‘outsmarted themselves’ with complex charges, expert says

- Share via

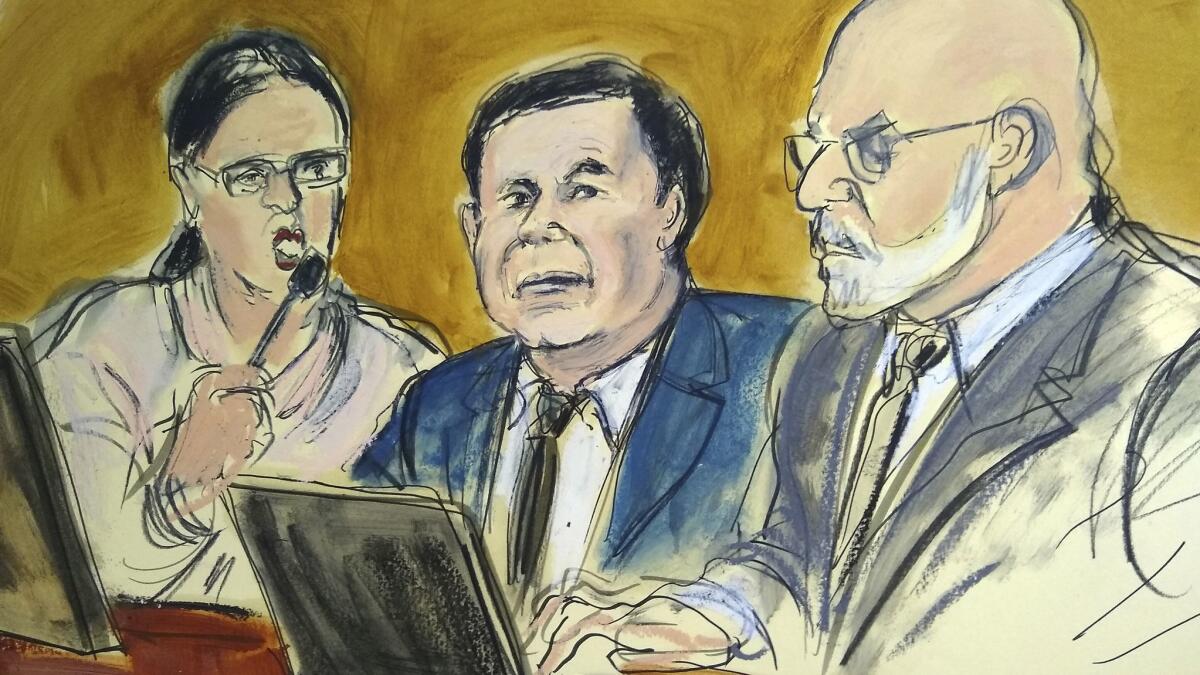

Reporting from New York — With two notorious prison breaks under his belt, a diamond-encrusted pistol on his hip, and a self-aggrandizing interview with Rolling Stone, Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman seems to have done a pretty good job convincing people across the globe that he’s one of the most powerful drug kingpins in modern history.

The question remains, however, whether the prosecutors who have tried the federal case against Guzman have been as persuasive to the only 12 men and women in the world who now matter: the jurors deliberating behind closed doors in a Brooklyn federal courthouse.

The exhaustive case against the 61-year-old, one that was a decade in the making, is certainly the government’s to lose. Prosecutors offered mountains of evidence in the monumental 12-week trial, including scores of intercepted phone calls and texts allegedly capturing Guzman arranging drug deals, and hours of testimony from his closest associates, giving an unprecedented view of the inner workings of his Sinaloa cartel — the brutal, multibillion-dollar narcotics empire prosecutors say he helped build over decades.

By contrast, Guzman’s defense team — which argued throughout the trial that Guzman was framed in a multinational conspiracy, with the help of the “lying” cooperating witnesses for the prosecution — presented a 30-minute case, with a single witness: an FBI agent who seemed less than comfortable with being called to the stand.

The jurors, who spent last Monday through Thursday deliberating — and will be back at it on Monday — are certainly not speeding through their decision.

If prosecutors thought their sweeping case would be handily won, the jury is not obliging. But four days deliberating after such a long and intense trial should not be cause for government alarm, legal experts say — though it could be a sign that the charges, as constituted, have made it unnecessarily difficult for jurors to find Guzman guilty.

So what’s going on? The men and women faced with deciding the infamous drug boss’ fate have a particularly complex set of charges to parse through — there are 10 counts in a 25-page charging document covering accusations that he sold and manufactured hundreds of tons of cocaine, methamphetamine and heroin; conspired to murder a host of rivals; and helped run one of the world’s largest international drug cartels. Jurors have all the counts laid out on what’s called a verdict sheet, which is eight pages long. They also had more than two hours of instruction on how to decide on the charges, some of which are interlinked. Some counts come with multiple yes or no questions jurors must answer, and one, the first count, includes 27 separate violations to decide upon.

Count one, engaging in a continuing criminal enterprise, essentially accuses him of being the mastermind behind the vast cartel. Guzman must be found guilty of at least three violations for him to be found guilty of the count. If he is guilty of count one, he would receive a mandatory life sentence.

“I respect the jury for being careful here,” said Laurie Levenson, a professor of criminal law at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. “They’re not just checking the boxes here. At least some seem to be weighing the charges, and being just as methodical as the government was in presenting the case.”

The verdict sheet the jurors must fill out is unusual in its complexity, Levenson said — but so is the case. “There aren’t many El Chapos out there.”

What makes the verdict sheet particularly trying is that first criminal enterprise charge; it’s rarely used, because it’s so difficult to prove, said Jimmy Gurule, a law professor at Notre Dame and a former federal prosecutor who prosecuted drug kingpins in Los Angeles.

There’s also the fact that some of the charges are cross-referenced. Jurors, for example, are instructed that they can find Guzman guilty of violation 27 under count one, which is murder conspiracy, only if they’ve also found him guilty of count two (conspiracy to manufacture and distribute cocaine, meth, heroin and marijuana), count three (cocaine importation conspiracy) or count four (cocaine distribution conspiracy). To make things even more complex: Some of the violations under count one are themselves separate charges. For example, violation 13 in count one, international cocaine distribution, is the same as count five.

“Prosecutors may have outsmarted themselves with these charges and made them overly complicated for jurors,” Gurule said. “It’s a very heavy lift for jurors to get through.”

Even if there weren’t all the “connecting the dots” among the charges, the case would still be very tough for jurors to process, he said.

“The reason it’s so hard to prove that top charge is that when you’re a drug boss, it’s not like you’re the guy out there selling the drugs — he’s running an international business, with tentacles in countries around the world, he’s delegating to hundreds of people,” Gurule said. “That means when prosecutors charge him with a crime based on a specific drug bust, jurors have to often decide if they believe the cooperating witnesses, who are themselves drug dealers, or other corroborating evidence, that El Chapo was the man directly behind it — it’s not so straightforward.”

Although legal experts say it’s unlikely Guzman will be fully acquitted, it’s very possible jurors will come back with different decisions on a variety of charges. “You have to remember that each count stands or falls on its own,” Gurule said. “They could be hung on some charges, acquit on some charges and find him guilty on others.”

Juries are allowed to be inconsistent in their verdicts, according to experts, but if the verdicts are egregiously contradictory, the defense might have grounds for an appeal. If the jurors remain hung up on some counts but issue verdicts on others, the government could seek to retry those counts.

With the large-scale drug-trafficking charges against him, even a guilty verdict on a couple of the drug counts — even without the top criminal enterprise charge — could still easily send Guzman away for life, experts said. But when it comes to juries, nothing can be taken for granted.

“At the end of the day, the burden is completely on the government to prove each and every charge beyond a reasonable doubt,” said Thaddeus Hoffmeister, a law professor at the University of Dayton. “And the truth is, no one can ever know what a jury is going to do.”

Plagianos is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.