Justice Department won’t charge officer, calls for Ferguson police reform

- Share via

Reporting from Ferguson, Mo. — Months after the killing of an unarmed black man by a white policeman convulsed this city and led to protests across the nation, the Justice Department decided not to charge the officer but called for substantial change in the police department, which investigators found had engaged in a pattern of racial abuse against African Americans.

In two reports released Wednesday, the Justice Department suggested 26 recommendations for the police department and the local courts, including added sensitivity training for officers and a ban on ticketing and arrest quotas that targeted blacks.

The department said it chose not to charge Darren Wilson, the white officer, because there was no evidence that he willfully deprived Michael Brown of his rights by using force beyond what police are legally empowered to use.

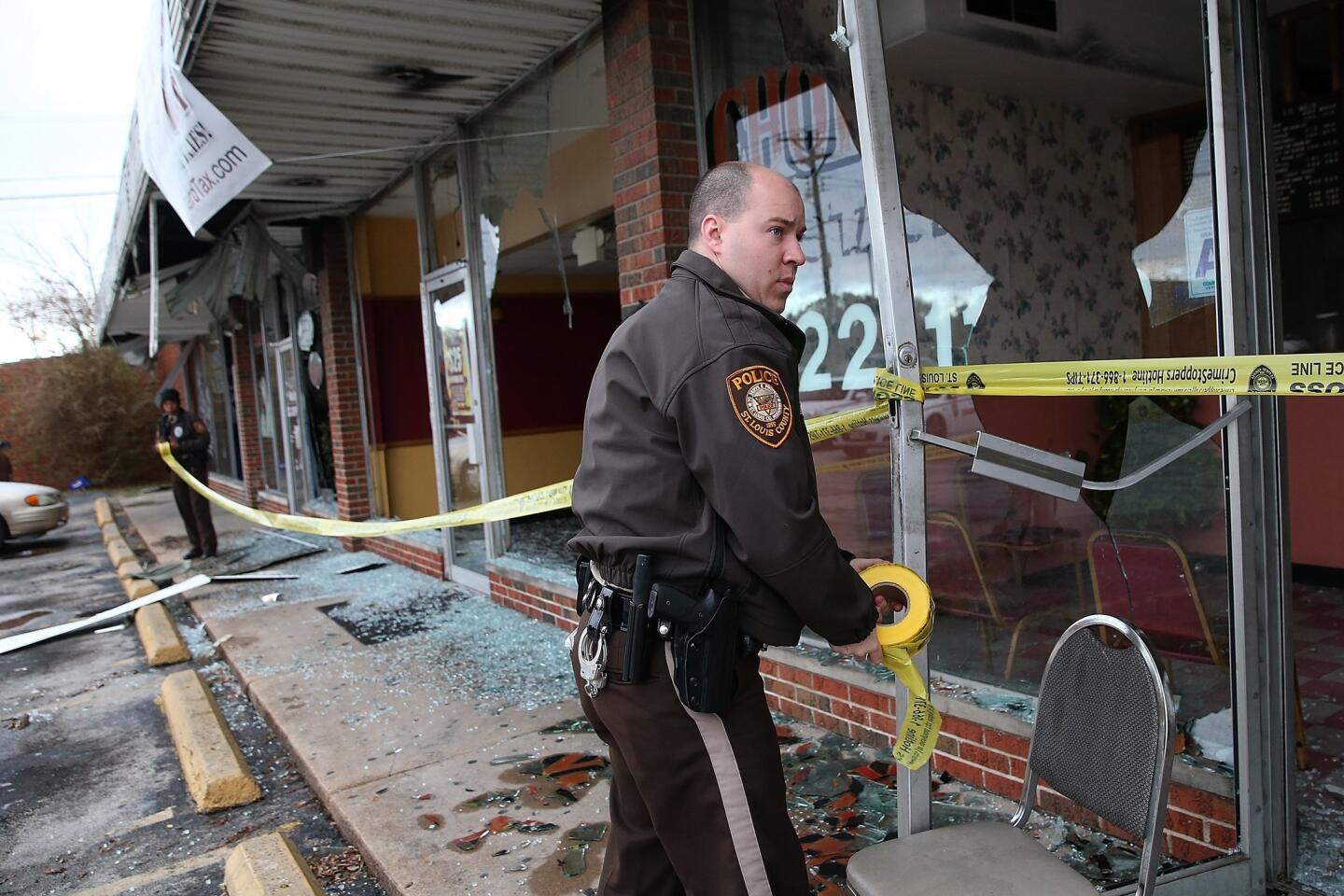

The report found no evidence to disprove Wilson’s testimony to a St. Louis County grand jury that he feared for his safety during the Aug. 9 confrontation. The grand jury declined to file charges, setting off a second wave of violent demonstrations in November.

Nor could investigators find credible witnesses and evidence to back up claims that Brown was shot as he tried to surrender and had raised his hands — a contention that inspired protesters’ slogan, “Hands up, don’t shoot!”

Ferguson Mayor James Knowles III told reporters at an evening news conference that the city had begun making changes in the police and court systems to respond to the Justice Department’s findings.

One police department employee has been fired and two others are on administrative leave awaiting a final ruling on their fate in connection with a series of racist emails exchanged by city workers, he said. One of the emails compared President Obama to a chimpanzee.

“Let me be clear,” the mayor said. “This kind of behavior will not be tolerated in the Ferguson Police Department or ... in the city of Ferguson.”

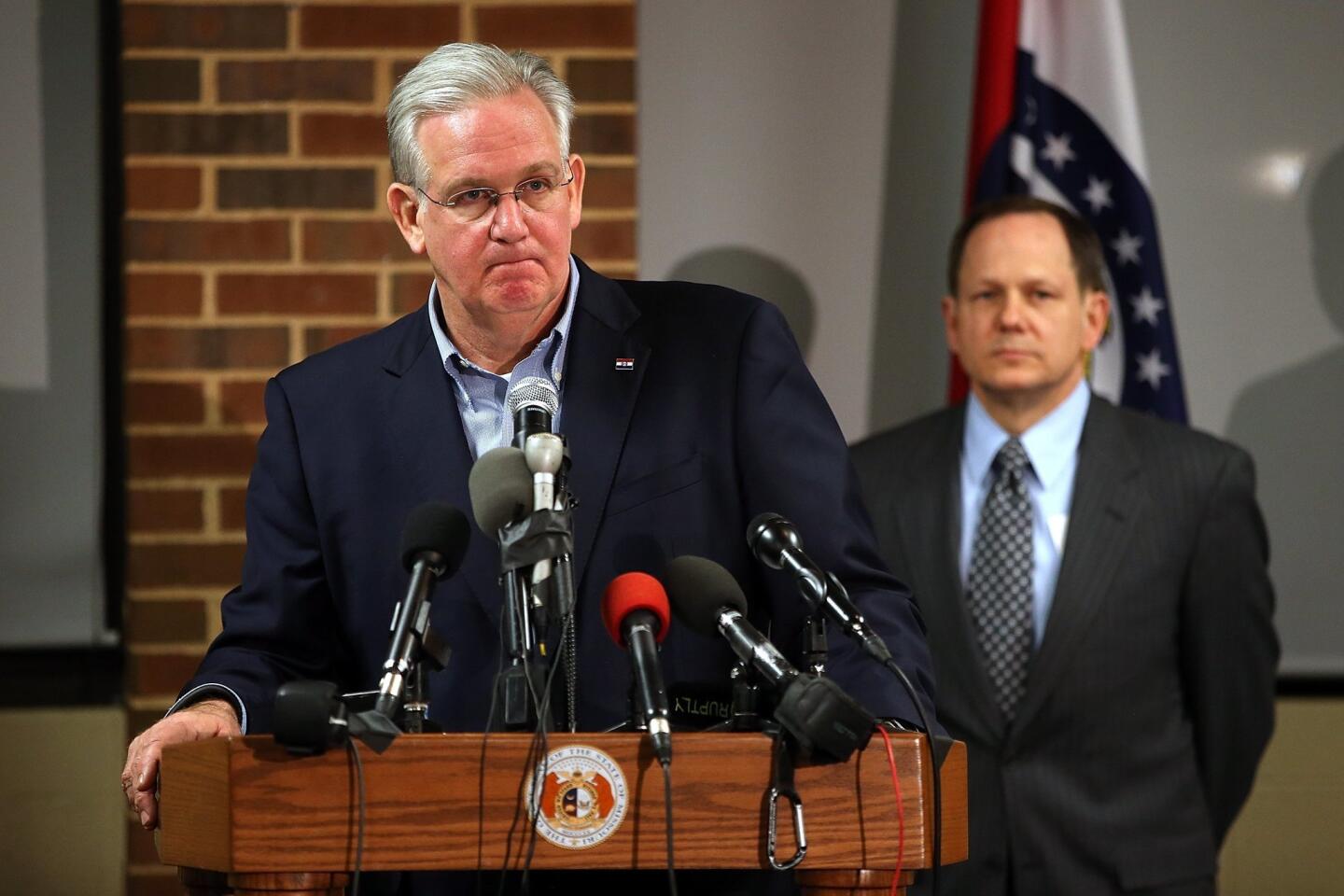

Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon said he was deeply disturbed by the Justice Department’s findings.

“Discrimination has no place in our justice system and no place in a democratic society,” Nixon said in a statement. “All Missourians deserve to be treated with fairness, dignity and respect.”

Earlier in the day, Brown’s parents, Lesley McSpadden and Michael Brown Sr., said their son’s death would not be in vain if it brought change.

“While we are saddened by this decision, we are encouraged that the DOJ will hold the Ferguson Police Department accountable for the pattern of racial bias and profiling they found in their handling of interactions with people of color,” the parents’ statement said. “It is our hope that through this action, true change will come not only in Ferguson, but around the country. If that change happens, our son’s death will not have been in vain.”

Former Mayor Brian Fletcher, who is campaigning for city council, said he wants to know what the Justice Department ultimately expects of the city.

“I never realized there was so much distrust,” said Fletcher, who is white and who served as mayor from 2005 to 2011.

But Cassandra Butler, a political scientist who has lived in Ferguson for 34 years and is African American, said she was more aware of the problems.

“We have a lot of work to do in the city,” Butler said.

The reports mark the end of one of the highest-profile cases during the tenure of Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr., the first African American to lead the Justice Department. Holder had visited Ferguson during the tempestuous days after the shooting.

“Some of those protesters were right,” Holder said, adding the phrase to his prepared text as he announced the findings Wednesday.

Holder has been criticized by conservatives for being too sympathetic to the protesters and too quick to step into the controversy over Wilson, who left the Ferguson Police Department last year.

The decision not to prosecute Wilson had been expected. Officials in recent weeks said the case did not meet the higher standards required for a federal civil rights prosecution.

The Justice Department report described a widespread pattern of racial discrimination that had turned Ferguson into a “powder keg” by the time the local grand jury declined to indict Wilson. Although Holder said violence is never justified, he said the “highly toxic environment, defined by mistrust and resentment,” contributed to the unrest.

“In a sense, members of the community may not have been responding only to a single isolated confrontation,” Holder said, “but to a pervasive, corrosive and deeply unfortunate lack of trust.”

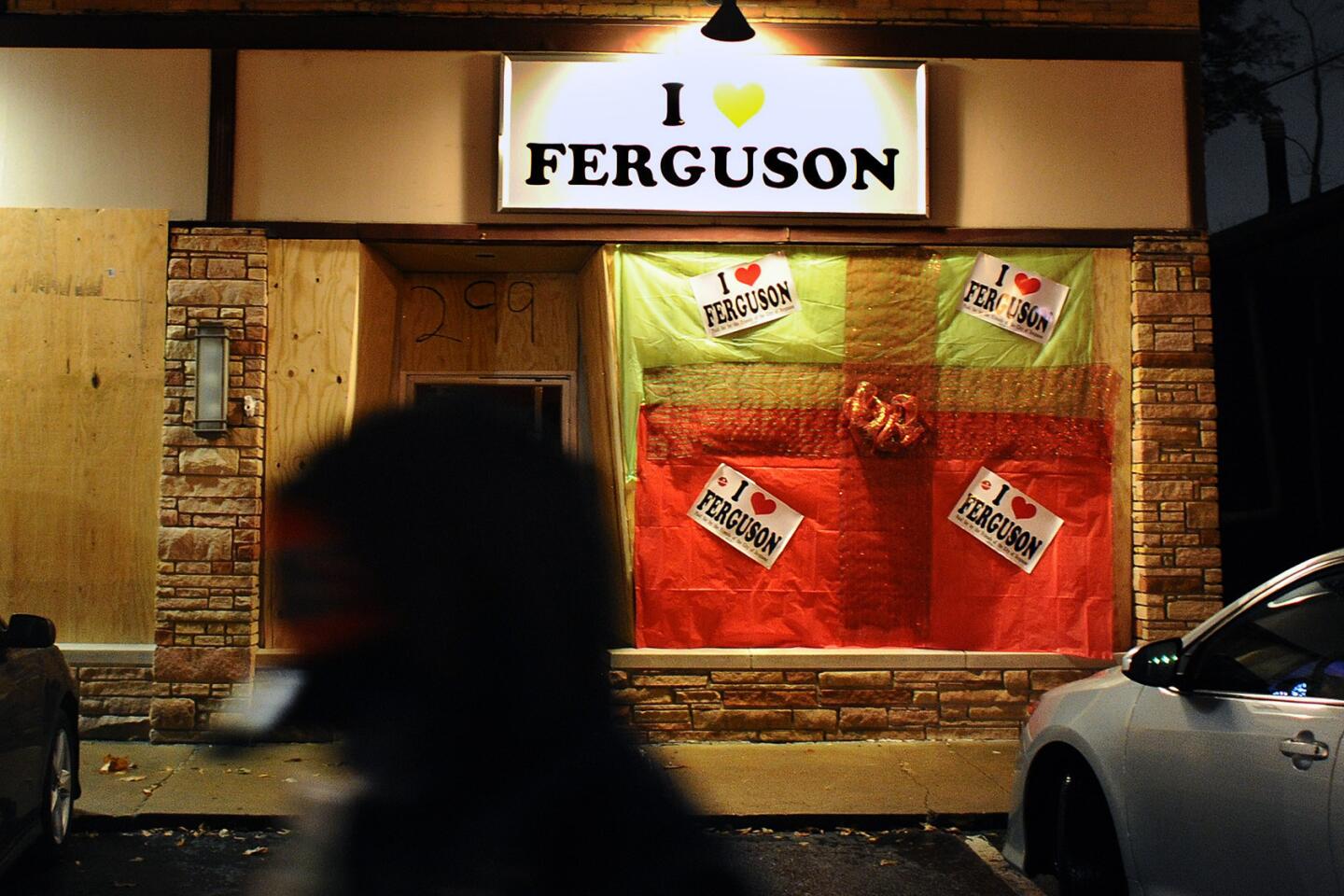

At Prime Time barber shop on West Florissant Avenue, site of protests and looting last fall and summer, barber Toriano Johnson watched the news on television and said he hoped the city would respond by cleaning house.

“They need to clean the whole department out and try to diversify,” said Johnson, 39, as he sat in the busy shop Wednesday.

If the police chief and the department are not replaced, he said, “it’s not going to be enough for the neighborhood. They got to remove the chief. They need to clean out the whole department for the community to see they’re making a change.”

He said the report on Officer Wilson “doesn’t surprise anyone.”

Next door at Ferguson Burger Bar, owner Charles Davis was also watching the news and hoping the Justice Department’s report would lead to an overhaul of the police department and of the city “command structure.”

“They just have to have somebody in charge to reprimand people if they don’t do things right,” said Davis, 47. “You have to get somebody in there with a different mind-set.”

African Americans make up about two-thirds of the population of Ferguson, about 10 miles northwest of downtown St. Louis. At the time of the Brown shooting, only three of 53 city police officers were black.

Late Wednesday, protesters blocked traffic in front of the Ferguson Police Department. They carried familiar signs: “Black lives matter” and “No justice, no peace.” They chanted, “Killer cops have got to go!”

A white male driver who was forced to turn around shouted a racial epithet at the crowd.

About 60 demonstrators braved temperatures in the low 20s as 10 p.m. neared. About 20 riot police stood next to the building.

Margaret Morrow, 67, a retired auto worker from St. Louis, said she had come despite the cold because the Justice Department “failed us.”

“I want them to get rid of everybody in the police department,” said Morrow, who is African American.

She stood across the street from the crowd with Cathy Jackson, 62, a retired bus driver, who is white.

“I don’t understand how the DOJ can say this is a racist department, they were racially profiling, but on the day Michael Brown was shot, that officer didn’t violate his civil rights,” Jackson said.

At least three demonstrators were arrested shortly after 10 p.m. It was unclear for what. By 10:30, more than half of the crowd had dispersed.

Under Holder, the Justice Department has conducted about 20 investigations of police departments in the last six years. Holder has announced he is stepping down.

Justice Department investigations that find wrongdoing usually lead to a consent decree with the municipality, and an independent monitor is appointed to oversee the recommended changes, including the retraining of law enforcement officers.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.