Congress is urged to honor little-known Revolutionary War hero

- Share via

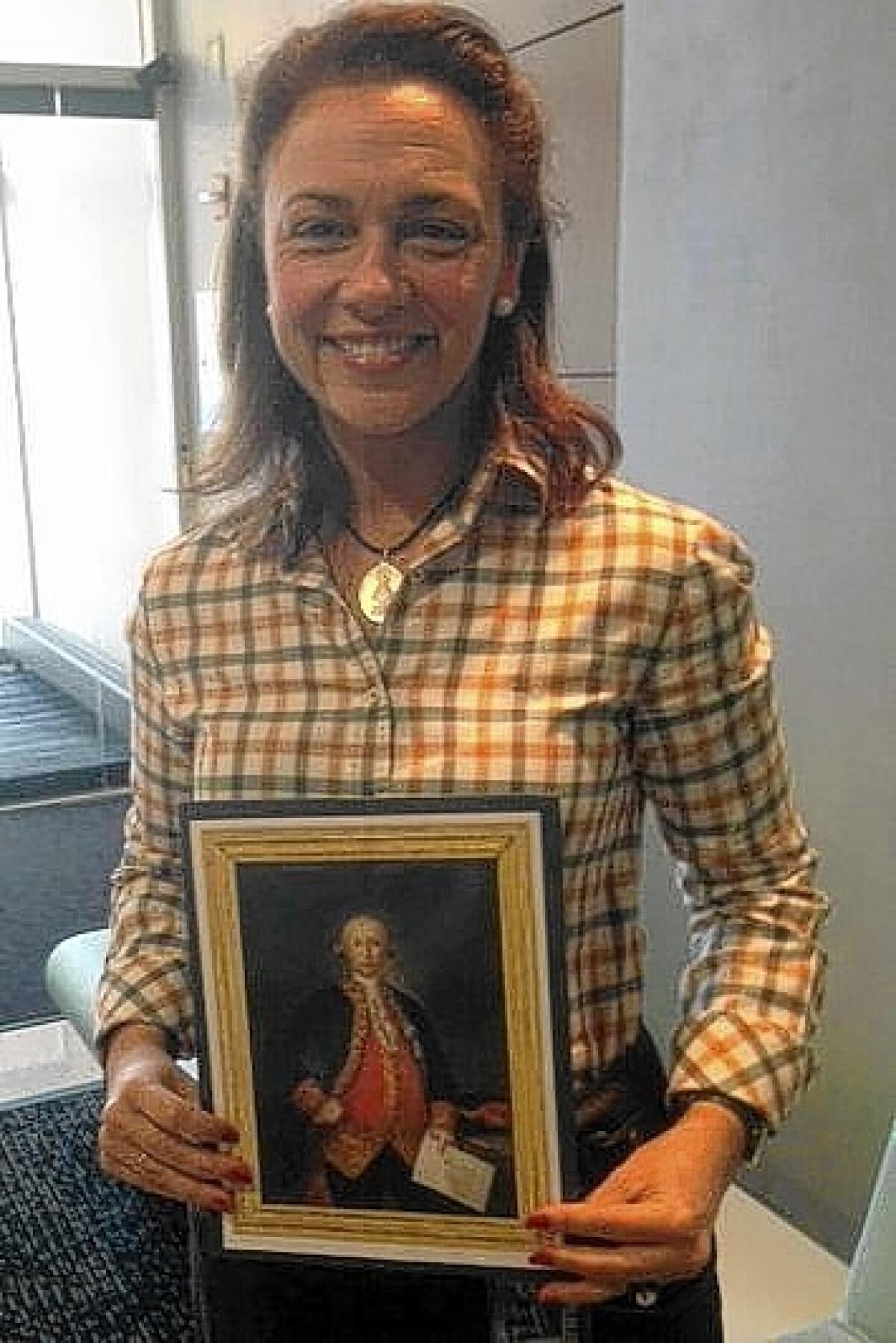

Reporting from Washington — Teresa Valcarce wants to see Congress keep a promise it made in 1783.

Back then, the year the Revolutionary War ended, Congress agreed to display a portrait of Bernardo de Galvez in the Capitol to honor the Spanish statesman’s efforts to aid the colonies in their struggle against Britain.

A group out of Pensacola, Fla., meanwhile, wants to see Galvez granted honorary citizenship, an honor bestowed on such notables as Lafayette and Churchill.

Never heard of Bernardo de Galvez? Exactly.

He is perhaps the Rodney Dangerfield of the American Revolution. But Valcarce, a Spanish immigrant who obtained her citizenship six years ago, and the Pensacola group hope to remedy that.

Galvez was governor of Louisiana during the reign of King Carlos III. He sent arms and supplies to the colonists and, after Spain’s entry into the war in 1779, led attacks on British outposts in the Gulf Coast area.

His actions, according to the U.S. Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad, “relieved British pressure on Washington’s armies.” In Pensacola, when Spanish ships were slow to attack the British capital of West Florida, Galvez sailed into the harbor alone, according to the Defense Department’s “Hispanics in America’s Defense.”

“Shamed and inspired by his example of personal leadership and bravery, the remaining ships followed,” the report says. Galvez’s coat of arms later included a ship with a flying pennant that says, “Yo Solo,” or “I alone.”

“As Lafayette was the symbolic representative of France, Bernardo de Galvez should be the symbolic representative of Spain,” says a report sent to Congress by Pensacola residents backing honorary citizenship. “Both countries provided vital support to the continental government, yet Spain’s influence often has been overlooked.”

It’s not as if Galvez has been entirely forgotten. Galveston, Texas, is named after him. A 15-cent postage stamp was issued in his honor in 1980.

He is lesser known than other Revolutionary War heroes, such as the Marquis de Lafayette, whose portrait hangs in the House chamber, and Thaddeus Kosciuszko, who has a bust in the Capitol and a street named after him in downtown Los Angeles, albeit a very short one.

Washington has a statue of the Spaniard astride a horse, a 1976 bicentennial gift from Spain, but it often draws the same response from passersby: Who?

“I gave a talk to 200 people in Galveston, Texas, and three people raised their hands when I asked if they knew where the town’s name came from,” said Thomas E. Chavez, author of “Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift.”

Recognition of Galvez, he said, “will open up a whole new world of information about the birth of our nation and will take an already beautiful story and make it better.”

Valcarce was unaware of Galvez’s role in the revolution until she visited Mobile, Ala., site of one of his battles.

“We were just walking around the city,” she said. “Suddenly, I saw the symbol of Malaga.” It was a statue of a fisherman carrying baskets on his shoulders — identical to one in the Spanish province where Galvez was born. At the time, Valcarce was living in Malaga (then a sister city of Mobile). Then she spotted a plaque describing Galvez’s exploits.

That was 16 years ago. Recently, Valcarce read an article in a Spanish newspaper saying the Continental Congress had accepted a portrait of Galvez.

That launched the 45-year-old mother of three from the Washington area on a mission to get a newly commissioned portrait of Galvez hung in the Capitol. “I am only asking my country to keep its word,” she said.

The Continental Congress in 1783 voted to accept New Orleans merchant Oliver Pollock’s offer of a portrait of Galvez “to be placed in the room in which Congress meet[s],” according to the Journals of the Continental Congress.

But whether a portrait was ever put on display is unclear.

Valcarce, who works as an administrative assistant, has pored through historic records, visited congressional offices and raised the matter with the Spanish prime minister during a recent gathering at the Washington home of Spain’s ambassador to the U.S.

“The guy who picks up the phone at the Historical Office of the Senate calls me ‘the Lady of the Portrait,’” she said.

Valcarce has lined up support for her cause, and a group is ready to donate a new portrait.

“If we make a promise to hang a portrait of the Spanish hero of the American Revolution in the U.S. Capitol building, and we can honor that promise without spending a nickel, why don’t we?” said Joseph W. Dooley, president general of the 33,000-member National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution.

The case of honorary citizenship was floated in the past, but gained new impetus after Galvez was named a Great Floridian by the state in 2012. “Almost everyone in Pensacola knows about this magnificent Spaniard,” said Nancy Fetterman, a volunteer historian.

Rep. Jeff Miller (R-Fla.), who represents the area, introduced the citizenship legislation, lining up the support of the Florida House delegation.

But it won’t be easy. The last time Congress awarded honorary citizenship was in 2009 to another Revolutionary War general, the Polish-born Casimir Pulaski.

Others conferred the honor were Lafayette; Winston Churchill; Mother Teresa; Pennsylvania founder William Penn and his wife, Hannah; and Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who rescued thousands of Jews from Nazi death camps.

Honorary citizenship has been proposed for others, including Anne Frank, Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Anwar Sadat. None got it.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.