As Hurricane Matthew approaches South Carolina, many residents are staying put

How do hurricanes work? Here’s what you should know about “the greatest storm on Earth.”

- Share via

Reporting from Charleston, S.C. — Walking through Charleston on Wednesday morning, you could barely tell that Hurricane Matthew was approaching. As waves lapped against the Battery, a fortified seawall and promenade in the historic part of town, tourists strolled along, sipping cappuccinos, eating ice cream and snapping photos of workers boarding up some of the city’s finest candy-colored antebellum mansions.

“It’ll be fine – as long as we don’t run out of wine,” said Christine Harrison, a tourist from Houston, as she sauntered along the Battery with her husband, Travis. The weather was overcast yet mild, with a gentle, warm breeze ruffling the palm trees.

A total of 1.1 million people were told to evacuate 100 miles of South Carolina coastline on Wednesday, the state’s largest evacuation in 17 years. About 1,500 National Guard soldiers had been mobilized to help.

Matthew is not expected to arrive in South Carolina until the weekend, but Gov. Nikki Haley urged residents and visitors in Charleston and Beaufort counties to begin evacuating no later than 3 p.m. “The storm did slow down, and it did move somewhat, but we are not in stable territory yet,” Haley warned coastal residents at a news conference, noting that more areas are likely to be evacuated Thursday.

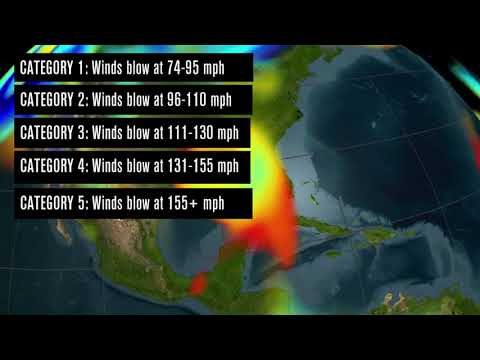

Florida, Georgia and the Carolinas have all called states of emergency in preparation for the storm that has pummeled Haiti and Cuba with 145 mph winds and storm surges. According to the National Hurricane Center, hurricane conditions “with the potential for life-threatening inundation” are possible along Florida’s east coast by late Thursday, with tropical storm conditions possible by early Thursday.

“For those of you that are wondering whether you should leave or not, I again will tell you that if you do not leave, you are putting a law enforcement officer or a National Guardsman’s life on the line when they have to go back and get you,” Haley warned.

During morning rush hour, delays started to form on Interstate 26, the main road from Charleston to Columbia, as residents headed west ahead of the coastal evacuation order. But by midmorning the traffic was relatively normal, and many remained in the city, stocking up on supplies.

Some gas stations in and around the city were out of fuel. A long line of cars snaked around the parking lot of downtown Charleston’s Harris Teeter supermarket as residents piled carts with water, paper towels, eggs, beer and rotisserie chickens.

“I think we’re going to be OK,” said Ford Reese, 75, a retired sales rep, who filled his cart with 12 bottles of Chardonnay to take back to his 1830s home on Society Street. “We’re on high ground and the house has survived all the other hurricanes.”

Downtown was quieter than usual, lacking the usual sights of horse-drawn carriages on the cobblestone streets and Gullah women perched on the sidewalks making sweetgrass baskets. Yet many restaurants, cafes and hotels remained open, and some guides were still conducting tours.

Across the Ashley River on James Island, clusters of golfers in polo shirts and shorts were still teeing off on the lush, manicured grounds of the Country Club of Charleston.

As many locals piled into their cars to drive 100 miles west, some were headed in the opposite direction to homes on the water’s edge.

“I’m coming home to help my husband put up the shutters,” said Heart Bernados, 50, an artist who lives on Johns Island, as she landed at Charleston International Airport on Wednesday morning after a conference in Nashville. “I’m leaning towards leaving, but he wants to protect the house.”

Several residents said the storm didn’t seem too severe and they had too much work to leave.

“We don’t have 14 hours to sit in the car,” said Lyndsay Jordan, a 24-year-old law student, as she loaded water into a shopping cart at Harris Teeter. “We’re studying for our midterms.”

“It seems a little early to evacuate,” agreed Alon Faiman, 23, a fellow student. “I don’t think it’s going to be that bad. The eye of the storm is not even going to be close. But I’ve never been in a hurricane before….”

Others were hedging their bets. Waiting at a gas station in James Island to fill up his Nissan Versa, Bart Smits, a 38-year-old medical researcher, said he was sending his wife and children west without him.

“Still, if it gets really bad and starts to bend back to us, I might leave,” he said.

To prevent congestion, eastbound lanes were reversed on major routes, such as Interstate 26. Thousands of law enforcement officers and National Guard troops were posted at intersections to aid motorists, and a row of more than 20 military aircraft stood on alert at Charleston’s airport.

It was the first large-scale evacuation in South Carolina since Hurricane Floyd hit the East Coast in 1999, which caused major traffic congestion. Back then, the state didn’t reverse the highway lanes, and roads were backed up for hours.

Even with interstate lane reversals, some predict heavy gridlock. Many of the coastal communities around Charleston have boomed in recent years, with Charleston County alone growing by more than 80,000 residents since Floyd struck.

Throughout the day, the streets got quieter. Gradually, more residences, law offices and antique stores were boarded up.

As sandbags were installed outside the doors of the historic City Market on Wednesday afternoon, a few vendors were still at their usual stalls, plying baskets, everlasting roses and wooden bowls to a slow trickle of tourists in deck shoes and shorts.

Yet by 3 p.m., Michael Ellis, a 55-year-old sweetgrass basket maker, was about ready to pack up and return to his family in Hanahan, about 15 miles north of Charleston. Business was slow, but he didn’t think he would evacuate.

“This is just like a baby for us,” he said, shrugging. “But they say the storm is turning, so we have to be on the safe side.”

Slowly, as the evacuation order came into effect, the streets filled with service workers.

Not long after the last guest left the Church Street Inn, Joemetta Murphy, 25, a head of housekeeping, exited the brick building in her work uniform, swinging a plastic bag filled with a carton of chocolate milk and a pack of Reese’s Puffs. She wasn’t sure what she’d do when she got home.

“I’m not evacuating,” she said as she loaded her bags into her sedan. “I’d like to come to work tomorrow, but they’ve closed the place up. I don’t know what I’m going to do. All I do is work. Maybe I’ll watch movies and sleep.”

Jarvie is a special correspondent. The Associated Press contributed to this report.

ALSO

Federal contractor charged with stealing classified government information

Canadian government says it will implement a nationwide carbon tax by 2018

Colombian voters reject peace deal between the government and FARC rebels

UPDATES:

1:50 p.m.: This article was updated with additional quotes from residents and details throughout.

1:22 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details about the evacuations in South Carolina.

This article was originally published at 12:05 p.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.