Matt Bevin’s victory in Kentucky highlights Democrats’ Southern demise

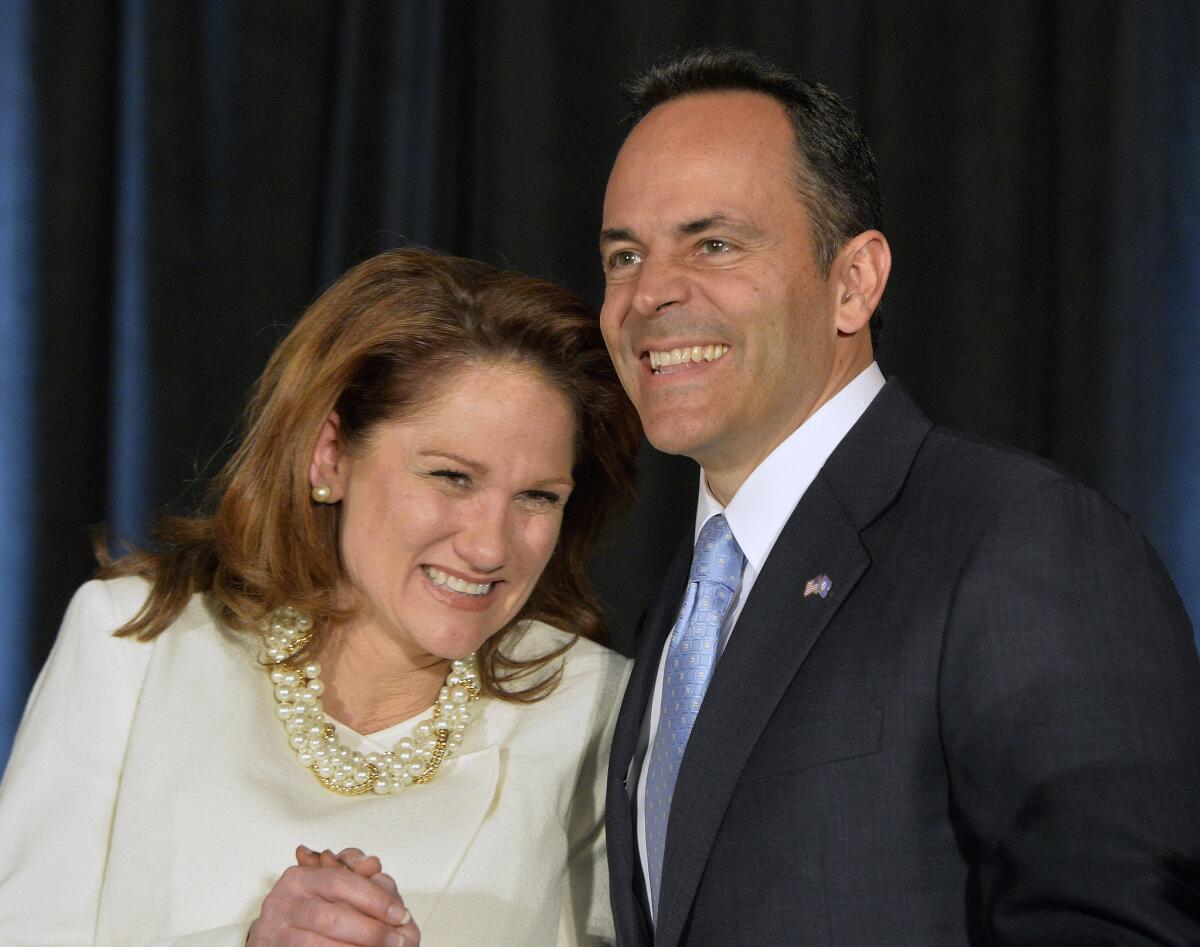

Kentucky Republican Gov.-elect Matt Bevin, right, and his wife, Glenna.

- Share via

The Democratic Party’s half-century of decline across the South was all but complete Wednesday after Kentucky elected a Republican governor who campaigned against abortion, gay marriage and, for a time, Obamacare.

The victory of tea party favorite Matt Bevin affirmed the appeal of outsider candidates challenging the establishment in a year when real estate mogul Donald Trump and retired neurosurgeon Ben Carson are leading the party’s presidential race.

Bevin, an investment manager who has never held public office, branded Democratic rival Jack Conway as a “career politician.” He ran television commercials calling Conway, Kentucky’s attorney general, “pro-abortion,” “anti-coal” and a champion of President Obama’s “liberal agenda” — reprising themes that swept many Republicans into office in last year’s midterm elections.

When Bevin is sworn in next month, Democrats will hold just two governorships in the South: Terry McAuliffe in Virginia and Earl Ray Tomblin in West Virginia. The sole legislative chamber that Democrats still control in the South is Kentucky’s House of Representatives.

“We’re sort of catching up to the rest of the South,” said Al Cross, a veteran Louisville political columnist and director of the University of Kentucky’s Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues.

The Democrats’ lock on the South began to erode after enactment of federal civil rights laws in the 1960s. The decline accelerated as the nation’s polarization over cultural issues intensified in the decades since then.

Kentucky’s shift away from Democrats has been slower than in some neighboring states, thanks partly to the 2005 indictment of its last Republican governor, Ernie Fletcher, in a political patronage scandal, Cross said.

For Bevin, Obama’s unpopularity in culturally conservative states like Kentucky proved a major asset. His advertising leaned heavily on tying Conway to the president.

Obama is also a major factor in the Nov. 21 runoff for governor of Louisiana, where Republican U.S. Sen. David Vitter is trying to use the president’s low popularity there to damage Democratic opponent John Bel Edwards.

Since 2008, when Obama won the presidency, Democrats have lost 13 governorships and more than 900 state legislative seats across the U.S.

In Kentucky, Bevin campaigned as a Christian conservative businessman who would protect coal mining, a backbone industry in the Appalachians.

Jim Cauley, a Democratic strategist in Louisville, said that timeworn tactic was especially effective in rural areas where the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is seen as a coal-mine job killer.

“There’s this feeling that the liberal Democrats are coming to get them,” Cauley said. “They don’t have Christmas because Barack’s coming at them with the EPA.”

Bevin highlighted his “pro-life” and “pro-family” stances. He stressed his opposition to Planned Parenthood and his support for Kim Davis, the Kentucky county clerk who spent several days in jail for refusing to obey federal court orders to issue marriage licenses after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriage was legal. Bevin paid her a jailhouse visit.

He also campaigned against Obamacare, a sensitive issue in a state where the Affordable Care Act has extended coverage to more than 500,000 people, mostly through an expansion of Medicaid under Democratic Gov. Steve Beshear.

Bevin wound up backpedaling on his initial pledge to stop the Medicaid expansion, saying he would continue to accept federal money to keep the newly insured covered but would require some of them to pay fees.

Bevin’s pivot came as Republican White House contenders, with a few exceptions, strike a less bellicose posture against the healthcare law than they did in 2012.

“We went from ‘repeal, repeal, repeal’ to ‘repeal and replace,’” said Jennifer Duffy, senior editor of the nonpartisan Cook Political Report. “That, to me, is shorthand for Republicans figuring out you couldn’t just talk about repeal. Maybe someone explained to them exactly what would happen if they repealed it.”

Former Kentucky Republican Chairman John McCarthy said Democrats had counted on a boost at the polls from many who gained health coverage, but “they didn’t show up to vote.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.