How college football helped bring down Missouri’s president

Supporters of Concerned Student 1950 celebrate University of Missouri System President Tim Wolfe’s resignation announcement in Columbia, Mo.

- Share via

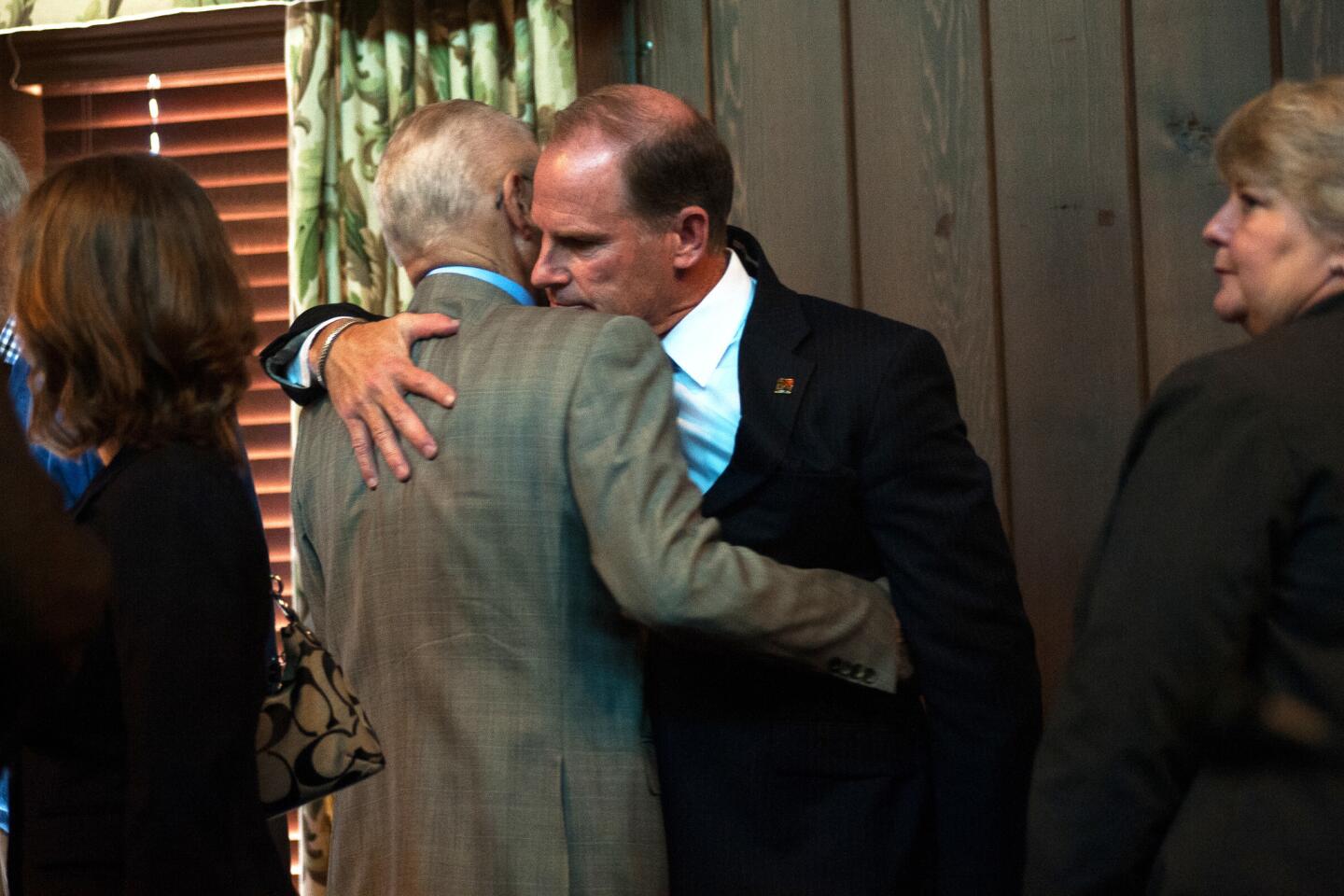

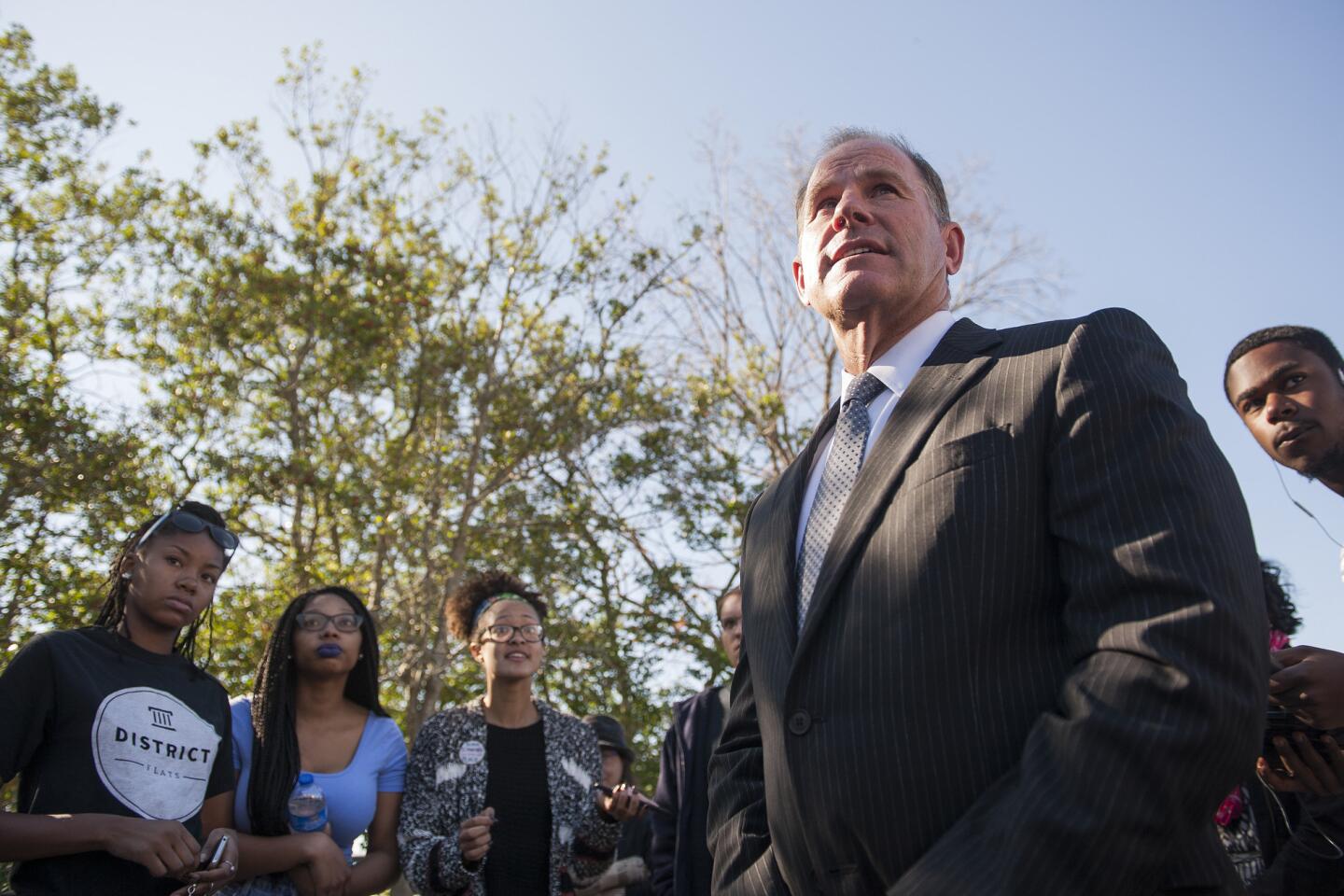

Tim Wolfe, the embattled president of the University of Missouri System, resigned Monday after months of turmoil with faculty, students and his economically powerful football team in open revolt over his handling of racial tensions.

It was the decision over the weekend by the football team to boycott activities, which would have cost the school $1 million, that broke Wolfe’s hold on the university’s top job.

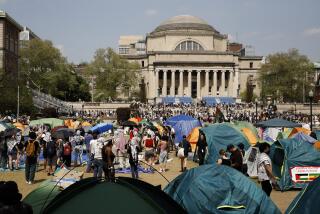

But an important hunger strike by a single graduate student helped mobilize public opinion, and a variety of protests by student groups and a threatened walkout by some faculty contributed to one of the most successful protests at a major university in recent years.

The University of Missouri was founded in 1839 in Columbia, Mo., as the first public university west of the Mississippi River and the first state university in the territory of the Louisiana Purchase. Missouri’s flagship campus is in Columbia, and there are three other campuses.

According to fall enrollment statistics, the school has about 35,000 students with about two-thirds coming from within the state. More than 27,000 are undergraduates.

The undergraduate population is about 79% white and 17.1% minority. Blacks make up about 8% of the student body. Missouri’s population is about 83% white and less than 12% black.

Sitting on the crossroads of the West and the South, Missouri has a more conflicted history on race that some areas. During the Civil War, Missouri was split in sympathy between the Union and the Confederacy which accepted Missouri but never fully controlled it.

Racial issues continued to plague the state, most famously in August 2014, when a white police officer shot and killed an unarmed black teenager, Michael Brown, in Ferguson, a northern suburb of St. Louis. The shooting and the decision by a grand jury not to charge officer Darren Wilson set off rioting and became the most visible outcome of more than a year of turmoil over the relations between minorities and police.

The protests in Ferguson had a broad effect, including about 120 miles west on the Columbia campus.

The Missouri Students Assn. in a letter on Sunday to the system’s governing body said there had been “an increase in tension and inequality with no systemic support” since Brown’s fatal shooting.

The Ferguson protests also helped push the #BlackLivesMatter hash tag in the social media universe, and that too had an impact in helping to spread the current uproar in Columbia. Last Friday, there were just a few hundred tweets about the University of Missouri. On Sunday, there were nearly 16,000. By Monday, after the resignation, it was up to about 60,000.

The protests at the university began early in the fall semester after Missouri’s student government president, who is black, said he was called a racial slur by the occupant of a passing pickup truck while walking on campus. Members of the Legion of Black Collegians, the leading voice for African Americans on campus, said racial slurs were directed at them by an unidentified person walking by. And a swastika drawn in feces was found recently in a dormitory bathroom.

During an Oct. 10 homecoming parade, black protesters blocked Wolfe’s car, and he did not get out and talk to them. The dissidents were eventually removed by police. Many of the protests have been led by an organization called Concerned Student 1950, which gets its name from the year the university accepted its first black student.

A final step came on Saturday night when black members of the football team joined the outcry. The white players quickly backed them up, as did football coach Gary Pinkel. By Sunday, a campus sit-in had grown in size, graduate student groups planned walkouts and politicians began to weigh in.

Even though the football team is having a losing season so far, its economic power is large. According to data compiled by USA Today, Missouri’s athletic program generated $83.7 million in revenue last year, on $80.2 million in cost — a net of $3.5 million in profit.

There was also an immediate scheduling issue. The Missouri Tigers’ next game is Saturday against Brigham Young University at Arrowhead Stadium, the home of the NFL’s Kansas City Chiefs. Cancellation could have cost the school a $1-million fine, according to a report in the Kansas City Star.

Follow @latimesmuskal for national news.

ALSO

Air Force struggles to add drone pilots and address fatigue and stress

Supreme Court gives police using deadly force in chases more immunity

‘Tale of two Californias’: Coastal voters upbeat on economy, inland residents anxious

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.