Immigrants lacking papers work legally — as their own bosses

- Share via

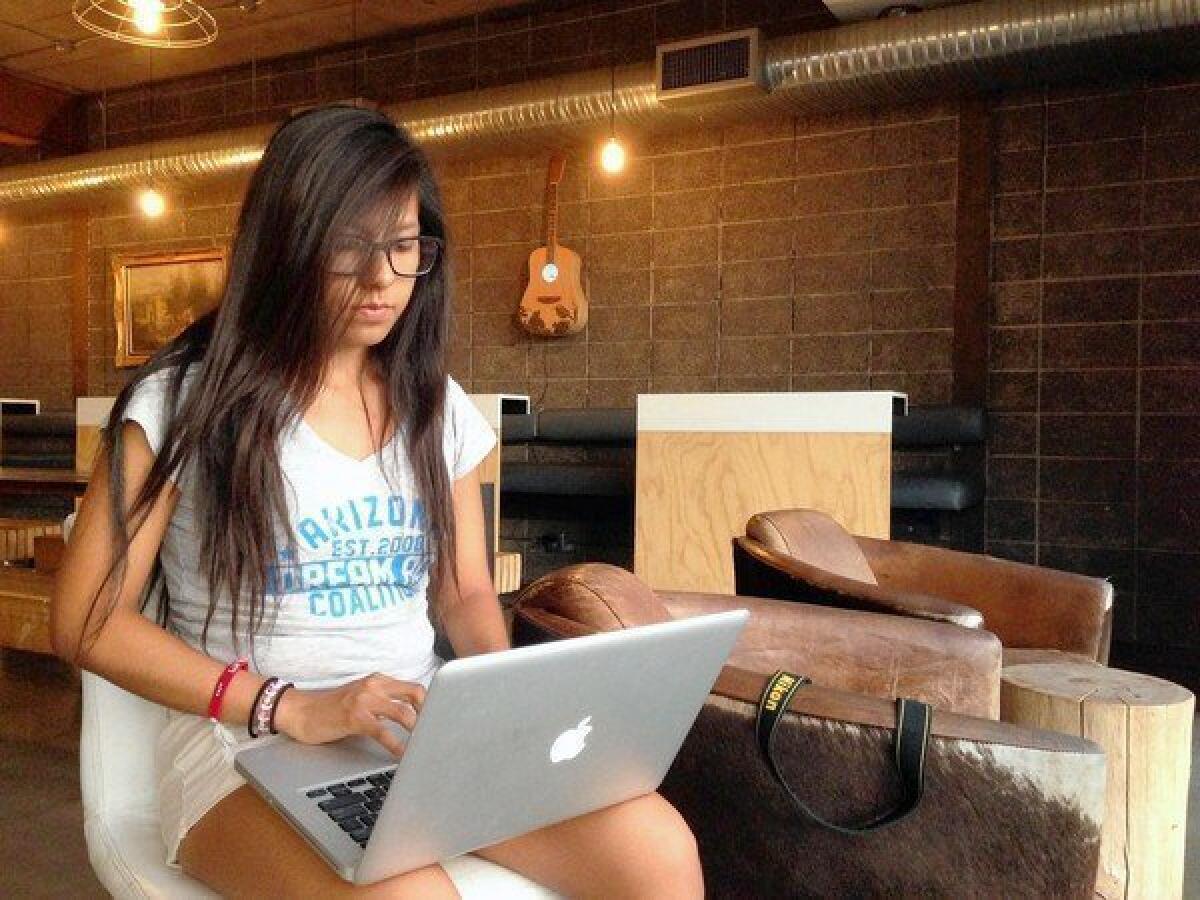

PHOENIX — At just 20 years of age, Carla Chavarria sits at the helm of a thriving graphic design business, launching branding and media campaigns for national organizations. Some of her projects are so large she has to hire staff.

Still, Chavarria has to hop on buses to meet clients throughout Phoenix because Arizona won’t give her a driver’s license. The state considers her to be in the country illegally, even though she recently obtained a two-year reprieve from deportation under the Obama administration’s deferred action program.

She may not drive, but along with thousands of other young people who entered the country illegally, Chavarria has found a way to make a living without breaking the law.

Although federal law prohibits employers from hiring someone residing in the country illegally, there is no law prohibiting such a person from starting a business or becoming an independent contractor.

As a result, some young immigrants are forming limited liability companies or starting freelance careers — even providing jobs to U.S. citizens — as the prospect of an immigration law revamp plods along in Congress.

Ever since 1986, when employer sanctions took effect as part of the immigration overhaul signed by President Reagan, creating a company or becoming an independent contractor has been a way for people who are in the country illegally to work on a contract basis and get around immigration enforcement.

But organizers who help immigrants said the idea has taken on new life in recent years, often among tech-savvy young people who came into the country illegally or overstayed visas.

Chavarria, who was 7 when she crossed into Arizona from Mexico with her mother, said her parents told her from a young age that anything was possible in her newly adopted country.

“We’re taught as young kids that this is the land of opportunity,” she said. “They told me, ‘You could be anything you want to be if you work hard, you’re a good person, obey your parents and go to school.’”

But when she graduated from high school in Phoenix, Chavarria discovered that her lack of legal status was a roadblock to becoming a graphic designer. Although she won a scholarship, she said, she could afford to take only two classes at a time at Scottsdale Community College because she wasn’t willing to risk working with fraudulent documents to pay for school.

Congress delivered another blow to Chavarria in 2010 when it failed to pass the Dream Act, which would provide a path to legalization for young adults who were brought into the country illegally as children.

The next year, after she became more involved with the Dream Act Coalition, she discovered a way she could sell her designs to others without fear of repercussions.

How is this possible? Though the issue is complex, the answer boils down to how labor law defines employees, said Muzaffar Chishti, an expert on the intersection of labor and immigration law at the Migration Policy Institute.

For example, employees often have set hours and use equipment provided by the employer. Independent contractors make their own hours, get paid per project by submitting invoices and use their own tools. Also, someone who hires an independent contractor isn’t obligated by immigration law to verify that person’s legal status.

At a workshop hosted by immigrant rights activists, Chavarria learned about these intricacies of labor law — and how to register as a limited liability company. “I didn’t know it was possible,” Chavarria said. “And it wasn’t that hard.”

It was as easy as downloading the forms from the Internet, opening up a bank account and turning in paperwork to the state along with a $50 fee. Proof of citizenship is not required. Regulations vary, but similar procedures exist in other states. In California, the fee is a bit higher and there’s an annual minimum tax of $800, but the process is similar to Arizona’s.

It’s unclear how many entrepreneurs there are like Chavarria. Immigration experts say anecdotal evidence suggests interest in such businesses has grown in recent years as more states have adopted tougher illegal-immigration laws. But research is scant.

Indications of a trend could be found, however, in a Public Policy Institute of California report on the effects of Arizona’s 2007 mandatory E-Verify law, which forced businesses to use a federal system intended to weed out people working in the country illegally.

The study found that 25,000 workers living in Arizona illegally became self-employed in 2009. That was an 8% jump over the number a year earlier. They probably formed limited liability companies, created their own businesses or even left employers to become independent contractors.

Freddy S. Pech, 25, a Mexican national who lives in East Los Angeles, said he decided to remain an independent graphic designer rather than form a limited liability company.

“I never found the need to create an LLC. I still pay my taxes and all that,” said Pech, who came to the country legally as a child but overstayed his visa.

Erika Andiola, a well-known Arizona immigrant rights activist who recently qualified for immigration relief under the federal deferred action program, said she knows many young people in the movement who created their own companies.

She started one as a political consultant and likes to say that if she ever listed all the entrepreneurs like her on a Facebook page, she could call it “the undocu-Chamber of Commerce.”

For some, starting a business can be too challenging.

Andiola had urged her brother, who works in construction, to form his own company. The idea didn’t go anywhere, however, because Arizona law says only U.S. citizens can qualify for the necessary permits for his line of work.

People who come to the U.S. later in life have other obstacles, said Mary Lopez, an associate professor of economics at Occidental College in Los Angeles, who specializes in labor and immigrant entrepreneurship.

The older generation tends to be less educated and distrustful of the U.S. banking and financial system. Not so the younger generation.

“We are talking about two different generations,” Lopez said. “The longer you stay in the United States and assimilate, the more financially aware you are.”

Lillia Romo, who was brought into the U.S. illegally when she was 4, started a school to teach English as a second language in 2009 in Phoenix. She can see the generational gap between her and her mother.

“We have more resources that our parents don’t have,” she said. “We feel more comfortable in the U.S. It can be intimidating for them. For us, it is just how it is.”

Romo and her mother run the school together, but not for long. The 25-year-old obtained immigration relief under the deferred action program and plans to get a regular job and finish school to follow her dream of becoming a doctor for the underserved.

Chavarria also qualified for relief under the federal program this year. Although she said the program gives her peace of mind, she doesn’t want to become an employee. She likes the autonomy of having her own business.

Most days, a coffee shop in Phoenix serves as her office, and she charges clients $350 to $5,000 per project. The first time she contracted workers for a large campaign, an odd thought hit her: Although others couldn’t hire her, she could hire others.

She also realized that her success had a larger significance.

“They say we’re taking money and jobs and don’t pay taxes,” Chavarria said of arguments made against immigrants in the country illegally. “In reality, it’s the opposite. We pay taxes. We create jobs. I’m hiring people — U.S. citizens.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.