Feds to help pay for tracking devices for autistic children

- Share via

NEW YORK -- The tragic case of Avonte Oquendo, a 14-year-old with autism who was found dead three months after running away from school, prompted Justice Department officials this week to expand a program to help parents obtain tracking devices for children with autism.

The announcement Wednesday means that federal grant funds, which already cover tracking devices for adults with Alzheimer’s disease, will also apply to children with autism. Sen. Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.), who had requested the funds, said the devices were available immediately for parents who wanted them.

Schumer also has proposed “Avonte’s Law,” a measure that would create a grant program specifically aimed at children with autism. It would allocate $10 million to the Justice Department for the program.

In a statement, Schumer said the department had “done the right thing” in providing grant money for children with autism in addition to adults with Alzheimer’s but that Avonte’s Law still was needed.

“The tragic end to the search for Avonte Oquendo clearly demonstrates that we need to do more to protect children with autism who are at risk of running away,” Schumer said.

With a tracking device, a parent, teacher or caregiver of a child with autism could notify the company that provided the device. Using GPS technology, the company could dispatch emergency responders to track the wearer. The devices, which Schumer said would cost about $85 each, can be worn on the wrist or ankle or clipped to clothing.

Schumer, quoting figures from national autism organizations, said 49% of children or teenagers with autism tend to run away or wander, often having close calls if they drift into traffic or near water.

Avonte, who was nonverbal, was at school in Queens when he ran off on Oct. 4 about 12:30 p.m. Video cameras captured him running down his school corridor and going out a door that had been left open. No security guards are visible, and he was unattended despite his special needs.

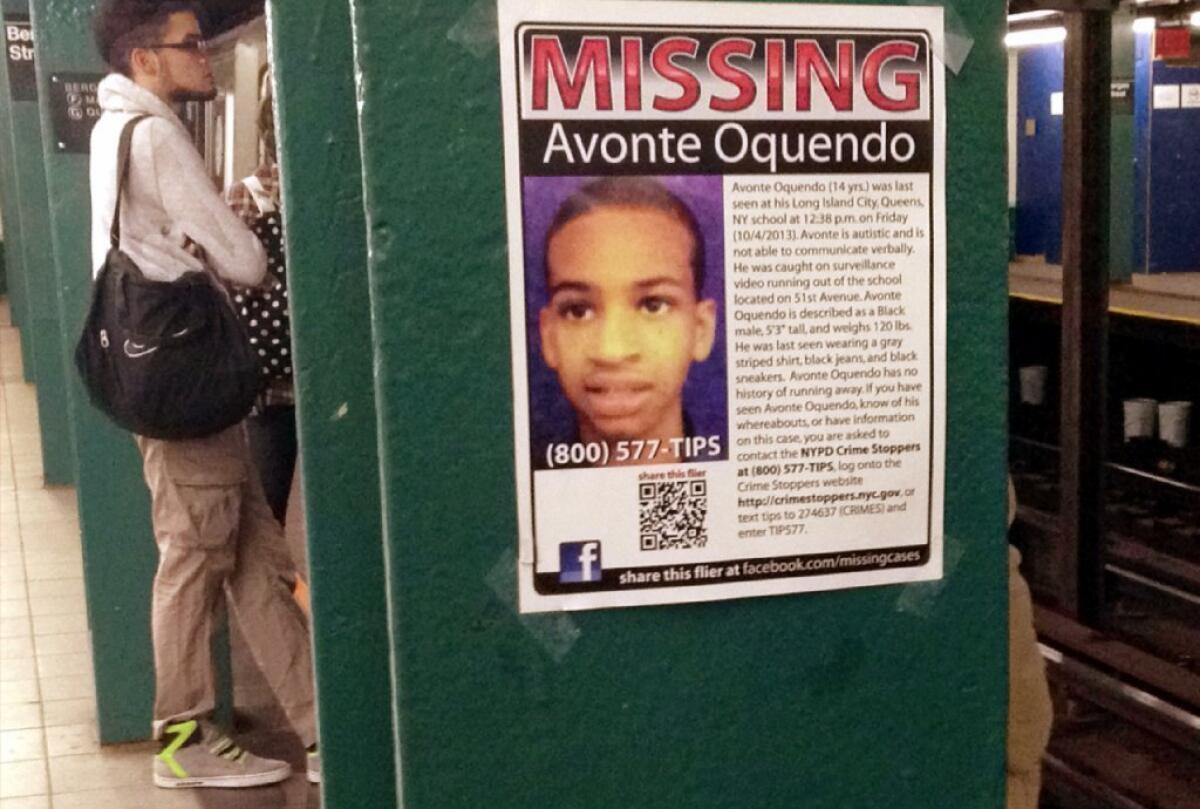

Police and the boy’s family launched a massive search with help from volunteers, who for more than three months plastered “missing” posters across the city. The boy’s remains were found Jan. 16 in the East River.

Avonte’s Law, which Schumer proposed in November, would authorize federal funds for the purchase of tracking devices as well as training in their use.

The idea is not without skeptics. Some parents say their autistic children would yank off any device attached to them or their clothing. Others express worries about privacy if the government is funding the devices.

Ashley Parker, a spokeswoman for the Autism Society in Bethesda, Md., said such tracking devices are available through private companies and nonprofit groups. Schumer’s proposal would mark the first time federal funds had been used to pay for them.

“We in general support anything that prevents the dangers that come with wandering,” Parker said. But she added that tracking devices alone were not enough.

Police and others called upon to help find a person with autism who has wandered away need training so that if they encounter the person, they know how to approach him or her, Parker said. That is especially true when the missing person does not speak.

Parker also said adults or older children with autism might have a legitimate reason, such as abuse, for wanting to get away from their caregivers.

“I think it’s a great idea for a lot of kids,” she said of tracking devices. “But there is always that concern that it could be used in a negative sense.”

Kpana Kpoto, the parent of a child with autism who appeared at a news conference with Schumer as he announced his proposed legislation, supports Avonte’s Law but said there would need to be “different options that different parents can try out.”

“Some children have sensory issues and may not want something on their wrist,” she said. “They may not want something on their ankles.”

Kpoto’s son is 6 years old. She said that when she heard about Avonte’s disappearance, “one of the first things I did was go online and try to find a tracking device” for her child.

A 2012 study by the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore found that children between the ages of 4 and 7 with autism were four times more likely to wander away than children of the same age without autism. The study, based on a survey of parents of children with autism, found that 49% of the children had tried to run off at least once after they reached age 4.

Avonte’s parents have filed a $5-million lawsuit against the city’s Department of Education, accusing school officials of failing to keep an eye on Avonte and alleging that they waited at least an hour before alerting his mother that her son was missing.

ALSO:

Shell abandons plan for Alaska offshore drilling

Across snow-struck Atlanta it’s a case of ‘Dude, where’s my car?’

Maryland mall shooter wrote in his journal that he was ‘ready to die’

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.