South L.A. student finds a different world at UC Berkeley

Kashawn Campbell overcame many obstacles to become a straight-A student. But his freshman year at Berkeley shook him to the core.

- Share via

School had always been his safe harbor.

Growing up in one of South Los Angeles' bleakest, most violent neighborhoods, he learned about the world by watching "Jeopardy" and willed himself to become a straight-A student.

His teachers and his classmates at Jefferson High all rooted for the slight and hopeful African American teenager. He was named the prom king, the most likely to succeed, the senior class salutatorian. He was accepted to UC Berkeley, one of the nation's most renowned public universities.

A semester later, Kashawn Campbell sat inside a cramped room on a dorm floor that Cal reserves for black students. It was early January, and he stared nervously at his first college transcript.

There wasn't much good to see.

He had barely passed an introductory science course. In College Writing 1A, his essays — pockmarked with misplaced words and odd phrases — were so weak that he would have to take the class again.

He had never felt this kind of failure, nor felt this insecure. The second term was just days away and he had a 1.7 GPA. If he didn't improve his grades by school year's end, he would flunk out.

He tried to stay calm. He promised himself he would beat back the depression that had come in waves those first months of school. He would work harder, be better organized, be more like his roommate and new best friend, Spencer Simpson, who was making college look easy.

On a nearby desk lay a small diary he recently filled with affirmations and goals. He thumbed through it.

"I can do this! I can do this!" he had written. "Let the studying begin! … It's time for Kashawn's Comeback!"

This is the story of Kashawn Campbell's freshman year.

Nothing had ever been easy for Kashawn.

"When I delivered him, I thought he was dead," said his mother, Lillie, recalling the umbilical cord tight around his neck. "He was still as stone but eventually he came to. Proved he was a survivor. Ever since, I've called him my miracle child."

Kashawn Campbell was a straight-A student at Jefferson High School in South L.A. But he is struggling at UC Berkeley. More photos

A single mom, she often worked two jobs to make ends meet, at times as a graveyard shift security guard. Someone needed to care for her baby, so she paid an elderly neighbor named Sylvia to house, feed and care for Kashawn.

"Me and Kashawn always had a strong connection," Lillie said. "But Sylvia raised my boy, yes she did."

Sylvia didn't read many magazines, newspapers or books. Only rarely did she take Kashawn outside their neighborhood. Still, she was kind and loving, and he loved her in turn, as if she were his grandmother.

"I used what she taught me and expanded it," Kashawn said. That meant deciding early on that the life he was surrounded by wasn't what he wanted his future to be. "I had to be the one to push myself to do beyond well…. If I didn't do that, nothing was going to ever change."

When I delivered him, I thought he was dead. He was still as stone but eventually he came to. Proved he was a survivor. Ever since, I've called him my miracle child."— Lillie, Kashawn Campbell's mother

Jefferson, made up almost entirely of Latinos and blacks, had a woeful reputation. His freshman year, just under 13% of its students were judged to be proficient in English, less than 1% in math.

"It was so rare to have a kid like Kashawn, especially an African American male, wanting that badly to go to college," said Jeremy McDavid, a former Jefferson vice principal. "We got together as a staff and decided that this kid, we cannot let him down."

By the end of his senior year, Kashawn's 4.06 grade point average was second best in the senior class. Because of a statewide program to attract top students from every public California high school, a spot at a UC system campus waited for him.

But when he got his acceptance letter from Berkeley, he couldn't celebrate like he always thought he would. It was Sylvia. She was losing a battle with cancer.

He sat near her hospice bed on a muggy day to give her the news. "I'm going to Cal, grandma," he said. She could barely open her eyes. "I'm going up there and I'm going to keep working hard and doing great. Nothing's going to change."

Sylvia died later that day.

A month later, when his mother drove him to Berkeley and dropped him off at his dormitory, Kashawn still crumbled into tears at the thought of Sylvia.

Yet he did everything he could to fit in. He lived at the African-American Theme Program — two floors in Christian Hall housing roughly 50 black freshmen, an effort to build bonds among a community whose numbers have dwindled over the last two decades.

To help prepare for his first college finals week, Kashawn Campbell attended as many study groups as possible. More photos

He filled his dorm room with Cal posters, and wore clothes emblazoned with the school's name. Each morning the gawky, bone-thin teen energetically reminded his dorm mates to "have a Caltastic day!"

"It was clear that Kashawn was someone who didn't know about, or maybe care about, social norms," said one of his friends. "A lot of people would laugh at first. They didn't understand how someone could be that enthusiastic."

But as the semester got going, he began to stumble. The first essay for the writing class that accounted for half of his course load was so bad his teacher gave him a "No Pass." Same for the second essay.

"It's like a different planet here," he said one day, walking down Telegraph Avenue through a mash of humanity he'd never been exposed to before: white kids, Asian kids, rich kids, bearded hipsters and burnt-out hippies. Many of them jaywalked. Not Kashawn. Just as he'd been taught, he only used crosswalks, only stepped onto the street when the coast was clear or a light flashed green. His shoulders slumped.

"I'm not used to the people. Not used to the type of buildings. Definitely not used to the pressure I feel."

Part of the pressure came from race. After peaking at 7% in the late 1980s and early '90s, the undergraduate African American population at Cal had been declining for years, especially since Proposition 209 had banned affirmative action in admissions to California public colleges. When Kashawn arrived, 3% of Berkeley undergraduates were African American.

Spencer Simpson spends time studying in his dorm room before class. Simpson grew up in Inglewood and attended Inglewood High. More photos

The low numbers were the source of constant talk on the theme program floors, the symbolic center of black life for Cal freshmen.

"Sometimes we feel like we're not wanted on campus," Kashawn said, surrounded at a dinner table by several of his dorm mates, all of them nodding in agreement. "It's usually subtle things, glances or not being invited to study groups. Little, constant aggressions."

He also felt a more personal burden.

He couldn't let his mother down. She kept a box stuffed with each of his perfect report cards. She swore that he was going to be a lawyer, maybe even the president. Back home her bank account was running low, and he sent some of his scholarship money home to keep her going.

He'd never been depressed. Now clouds of sadness descended every few weeks. When they did he was barely able to speak, even to Spencer, his roommate.

The biggest of his burdens was schoolwork. At Jefferson, a long essay took a page and perfect grades came after an hour of study a night.

At Cal, he was among the hardest workers in the dorm, but he could barely keep afloat.

Seeking help, he went at least once a week to the office of his writing instructor, Verda Delp.

Have a Caltastic day!"— Kashawn Campbell

The more she saw him, the more she worried. His writing often didn't make sense. He struggled to comprehend the readings for her class and think critically about the text.

"It took awhile for him to understand there was a problem," Delp said. "He could not believe that he needed more skills. He would revise his papers and each time he would turn his work back in having complicated it. The paper would be full of words he thought were academic, writing the way he thought a college student should write, using big words he didn't have command of."

At the end of the first semester, after he turned in a final portfolio of revised essays, Delp asked Kashawn to come to her office. She told him this last batch of work was better. After reviewing his writing, though, it was clear to her that he had received far too much help from someone else.

Both remember the meeting, recalling Kashawn's shock, his admission that friends and a tutor had offered suggestions and made edits, his insistence that the bulk of the writing was his own.

Kashawn Campbell takes a break from studying in his dorm room to chat with a friend on the phone. More photos

Delp reviewed his record: None of his essays had been good enough to receive passing grades. Still, instead of failing him, she gave a reprieve: His report card would show an "In Progress." The course wouldn't count against his grade point average, but he would have to take it again.

Before the start of the second term, hoping for a head start, Kashawn moved back into the dorm before anyone else on his floor. He imagined how different things were going to be from his first semester.

He couldn't wait to see Spencer. "We're both going to do very well this semester," he said. "I believe I can follow his lead and ace all my classes."

They hadn't known each other before the year began. Now they were like brothers, partly because they shared so much. Spencer was raised in a tough L.A. neighborhood by a single mom who had sometimes worked two jobs to pay the rent. Spencer had gone to struggling public schools, receiving straight A's at Inglewood High. Spencer didn't curse, didn't party, didn't try to act tough and was shy around girls.

As much as they had in common, they were also different. Spencer's mother, a medical administrator, had graduated from UCLA and exposed her only child to art, politics, literature and the world beyond Inglewood. If a bookstore was going out of business, she'd drive Spencer to the closeout sale and they would buy discounted novels. She pushed him to participate in a mostly white Boy Scout troop in Westchester.

A lot of people would laugh at first. They didn't understand how someone could be that enthusiastic."— One of Kashawn Campbell's college friends

To Spencer, Berkeley was the first place he could feel fully comfortable being intellectual and black, the first place he could openly admit he liked folk music and punk rock.

He was cruising through Cal, finishing the first semester with a 3.8 GPA despite a raft of hard classes. "I can easily see him being a professor one day," said his political theory instructor, noting that Spencer was one of the sharpest students in a lecture packed with nearly 200 undergraduates.

In the second term, Kashawn and Spencer volunteered for the same student organizations, and walked each Friday night to a job washing dishes at a nearby residence hall.

They even took a class together, African American Studies 5A, a survey of black culture and race relations. It was key for Kashawn: A top grade could ensure he would be invited back to Cal.

They sat together in the front row. One teacher noticed that Kashawn subconsciously seemed to mime his roommate: casually cocking his head and leaning back slightly as he pondered questions, just like Spencer.

Kashawn reveled in the class in a way he hadn't since high school. He would often be the first one to speak up in discussions, even though his points weren't always the most sophisticated, said Gabrielle Williams, a doctoral student who helped teach the class.

He still had gaps in his knowledge of history. But, Williams said, "you could see how engaged he was, how much he loved being there.... You could also see that he was struggling with his confidence, partly because this whole experience was so overwhelming."

Kashawn Campbell and his best friend, classmate and roommate Spencer Simpson, walk into their African American studies class. More photos

Although the African American studies class was a bright spot — Kashawn had received an A on an essay and a B on a midterm, the best grades of his freshman year — the writing course he'd been forced to repeat wasn't going well.

He knew that another failing effort in the class could doom his chances to return to Cal, so he worked as closely with his new instructor as he had with Delp.

There was little to show for the effort. On yet another failing essay, the instructor wrote how surprised she was at his lack of progress, especially, she noted, given the hours they'd spent going over his "extremely long, awkward and unclear sentences."

He told only Spencer and a few dorm mates how devastating this kind of failure felt, each poor grade another stinging punch bringing him closer to flunking out. None of the adults in his life knew the depth of his pain: not his professors, his counselors, any of the teachers at his old high school. He spoke vaguely about depression to his mother. She told him to read the Bible.

Spencer Simpson, left, and Kashawn Campbell chat before their African American studies class. More photos

Spencer looked out for Kashawn; he was the first person Kashawn would turn to when depression came. Sometimes in the dorm room, Spencer would look over at Kashawn and see him sitting in front of his computer, body frozen and face expressionless, JVC headphones wrapped over his ears, but no music playing.

One night Kashawn walked briskly from his room, ending up alone in a quiet, beige-walled lounge at Christian Hall. His mind raced. He chastised himself for his college grades, for being too sensitive, too trusting, too naive.

"Why was I even born?" he wondered. It felt like he was outside his body, looking at himself from above. "Is life really worth living under these conditions?"

He tried to calm down. "The way I was stressing myself out, it wasn't good, it wasn't healthy at all," he would recall later. "I just had to find my way out of that lounge. Had to get help, because this was a monster I needed to tame."

It wasn't long before he found himself sitting for the first time in a campus psychologist's office. The counselor urged him to put his life in better perspective. Maybe he didn't have to be the straight-A kid he'd been in high school anymore. Maybe all that mattered was giving his best. The visit seemed to change him. His dorm mates had been so worried about his dark moods that some had called their parents, asking advice on how best to help their friend. As weeks passed and his smile returned, everyone breathed a little easier.

"I've learned the hard way that academics are not who you are," Kashawn said as he walked through Sproul Plaza, heading back to the dorm one day in May. "They are something you need to learn to get to the next level of life, but they can't define me. My grades at Cal are not Kashawn Campbell."

Finals week. The school year was nearly over. After staying up all night to finish, Kashawn turned in the final portfolio for his writing course.

"I'm proud of you," his instructor said, as he handed her the essays in a black folder. "You've tried as hard as anyone I've ever seen."

Soon he'd taken his last test, turned in his last report. He stood on a sidewalk outside the dorm, saying goodbye to Spencer, stifling tears. Then he was on a Greyhound bus, heading home to Los Angeles, where he slept on the floor in his mother's apartment and waited for his grades.

I'm proud of you. You've tried as hard as anyone I've ever seen."— Kashawn Campbell's second semester writing instructor

Would he flunk out?

"All I can do is pray," he said.

One morning this summer he walked slowly to the kitchen table, sat in a black chair and cracked open his laptop. Cal's website had just posted grades.

He scrolled down the page and saw the results for College Writing. His teacher said he'd improved slightly, but not enough. She gave him an incomplete. To get a grade he'd have to turn in two more essays, if he came back to school.

His heart raced. He saw that he'd passed a three-unit seminar. He scanned further, his eyes resting finally on a line that said African American Studies 5A. There was his grade.

A-.

"Yes!" he exclaimed. An A- lifted his GPA above a 2.0.

He wasn't a freshman anymore. He would return to Cal for his sophomore year.

[For the Record, 1:39 p.m. PDT Aug. 18: In an earlier version of this article, a graphic design element highlighting the quotation “I'm proud of you. You've tried as hard as anyone I've ever seen” misattributed the comment to writing instructor Verda Delp. The words were spoken by Kashawn Campbell’s second-semester writing coach.]

Follow Kurt Streeter (@kurtstreeter) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

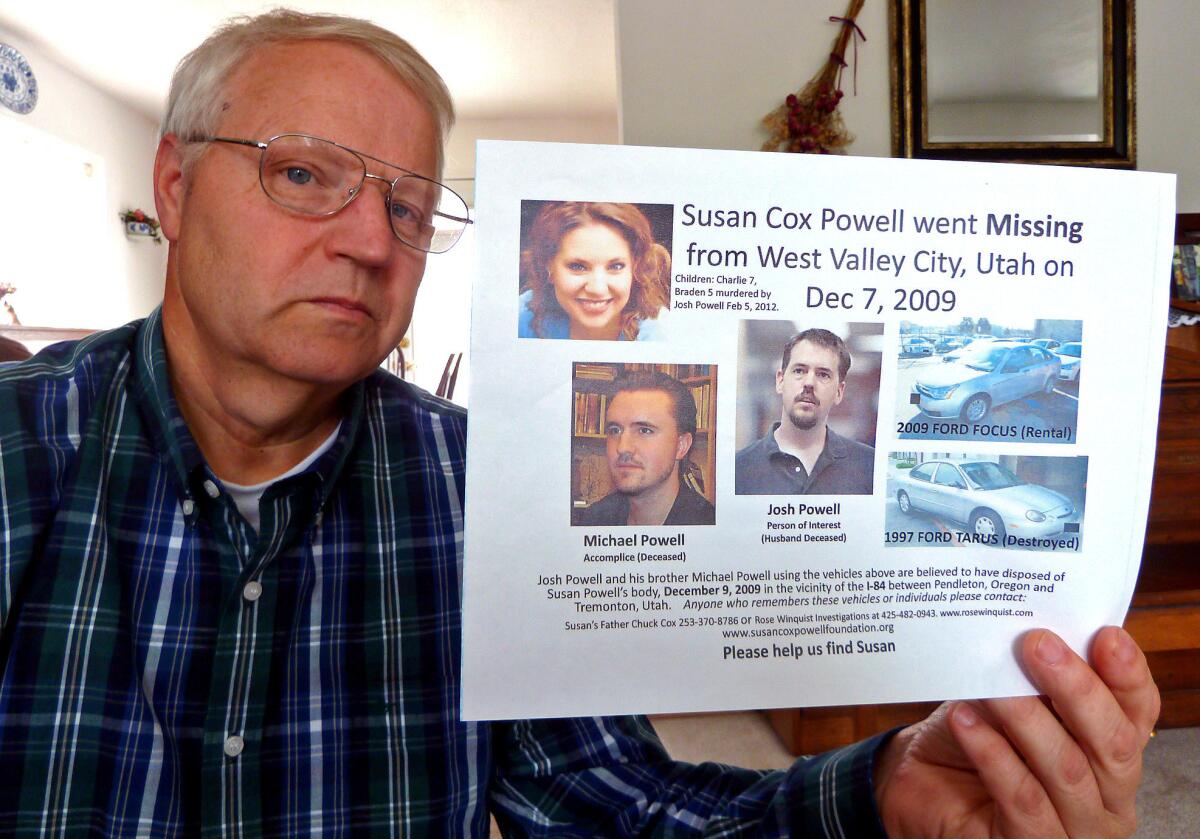

Susan Powell's father refuses to give up search after four years

"I just sat there thinking, 'I didn't want to be right. I just want to find my daughter.'"

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.