Next stop for Verbum Dei High’s disadvantaged students: college

In 2002, the Catholic high school in Watts began accepting only low-income students and doubling up on core classes. It’s working.

- Share via

The young man with braces and close-cropped hair as precise as a geometry lesson steps onto the stage at Verbum Dei High School, grabs the microphone and introduces himself.

"My name is Ricardo Placensia," he says, then lets out a nervous laugh. "I interned at Locke Lord law firm, and this fall I will be attending UC Riverside."

The crowd at the all-male Catholic school in Watts erupts in applause.

Later in the ceremony, another teenager with precision-cut hair — but no braces — takes his moment in the spotlight.

"Hi. I'm Roberto Placensia," he says. "I've been interning for four years at Keenan & Associates, and this fall, I will be attending the University of California, Riverside."

The excitement in the room approaches that of the National Signing Day frenzy televised on ESPN, in which heavily recruited high school athletes announce which college they've picked to attend.

But Verbum Dei no longer churns out top football and basketball players. This commitment day ceremony recognizes another kind of achievement.

By the end of the hourlong event, the entire Class of 2013 has made the same rite of passage as the Placensia twins:

All 60 announce they will be heading to college.

Faculty members call teacher Nic Hogan "The Guru" because of his two-decade tenure at Verbum Dei. He remembers the time the electricity went out in the heat of summer as teachers were preparing for the upcoming school year.

"We thought it was a power outage," he said.

It wasn't — the school was months behind on its bill.

In 2000, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles, which long kept the school afloat, announced that the school was having financial troubles and was on the verge of closing.

In front of their Watts home, Marlene Chapa talks with her twin sons Robert, left and Ricardo Placensia about their upcoming graduation night party. More photos

Despite the financial issues, the school remained an athletic powerhouse. In 2004, the school added its 14th basketball title. Two years later, Verbum Dei won a third football championship.

But the school was becoming a dumping ground, school officials said. Parents were turning to the school, hoping the religious component and discipline would straighten out their troubled teens.

"Back then, there were no real qualifications but the application," Hogan said. "We started to get the bad students, the borderline gang members.... We were almost a military school."

Then Cardinal Roger M. Mahony asked the Jesuits to take over and in 2002 linked the school with the Cristo Rey Network of Catholic schools, which provides a college preparatory experience for disadvantaged urban teenagers.

By 2009, Verbum Dei was fully operating under the new program. Only low-income students were accepted. Children of well-off alumni were rejected. Alumni were outraged.

You might not see any more championship athletic banners in the gym. But what you will see is five to six college acceptance letters per student."— Paul Hosch, Verbum Dei official

"I can understand what they're trying to do," alum Peter Watts said at the time. His son was turned down by the school because the family income was too high. "But I also see that they are not looking at the big picture."

But Verbum Dei has found a winning formula: For the sixth straight year, this year's college acceptance rate was 100% for its almost entirely Latino and African American students.

"You might not see any more championship athletic banners in the gym," said Paul Hosch, vice president for mission advancement at Verbum Dei. "But what you will see is five to six college acceptance letters per student."

Congratulation letters from UCLA, Cerritos College and Georgetown University cover the wall of a hall in the school. Ricardo and Roberto walk past it daily.

When the boys were toddlers, their mother, Marlene Chapa, tried to shield them from an abusive and drug-addicted father.

Chapa would lock her sons in a room where they were safe from their father's rage. The confrontations often left her battered and bruised, and on a few occasions hospitalized.

But it would be her sons who helped save her: When a social worker came to check on a child abuse complaint from a neighbor who heard the couple fighting, one of the twins fingered their father as the abuser.

Chapa was given two options: Leave her husband or lose her children. She chose the former, and never looked back.

For almost two years, the family lived in a shelter for battered women as Chapa worked on getting back on her feet. Although the family eventually moved out, they hopped from place to place.

During a party commemorating his years of internship at Locke Lord in downtown L.A., Ricardo Placensia shakes hands with Jon Rewinski, a partner in the law firm. More photos

Chapa tried to mask her struggles, smiling through the long hours unpacking boxes at the 99¢ Only store and working on a factory assembly line.

"She always had such a positive attitude," Ricardo said. "She never shows her frustration. She thinks she was fooling us, but she wasn't."

They finally settled in a tidy house on a Watts street where gunfire frequently broke the silence of the night.

Chapa tried to keep the children busy and focused, always pushing them to go to college. But Chapa knew this would be hard to accomplish at nearby Jordan High School.

"I was hearing it was one of the worst schools in the area," she said in Spanish. "As a single mother, I had to make sure they were in a safe place."

Chapa and the boys drove past Verbum Dei almost daily, but tall trees and an ornate gate hid the campus from view.

Students come to class wearing black slacks, white, button-down shirts and ties. The day is highly structured, its rigorous schedule designed to bring underachieving students to grade level.

"Every student here has obstacles or challenges, and we accept that," Principal Dan O'Connell said. "But that cannot be an excuse. The real world is not going to allow them to use that as excuses."

Most elective courses are eliminated, with double sessions of core classes such as English and math. The school condenses six years of learning into four. Every night, students take home mountains of homework.

Chapa thought the twins would thrive there, away from the pressures of their neighborhood.

But first, they had to be accepted.

Roberto flat out told his Verbum Dei interviewers that he didn't want to attend the school.

Every student here has obstacles or challenges, and we accept that. But that cannot be an excuse."— Principal Dan O'Connell

They ignored him. They saw promise and commitment: Unlike other reluctant applicants, Roberto had completed the tedious process.

The twins were accepted. During the six-week summer preparation program, they learned they had to maintain a job while juggling the rigors of high school.

"I started to realize what I was getting myself into," Ricardo said.

In addition to schoolwork, students work one day during the school week as part of a corporate work-study internship that pays half of their $15,000 tuition. Parents are asked to pitch in $2,700, but students aren't turned away if their families can't afford it. The rest of the tuition is made up through grants and fundraising.

The twins received a scholarship and their mother pays only $15 a month.

School officials said the work at law firms, banks and engineering companies inspires the teens. On the job, students are exposed to corporate boardrooms, marble walkways and fancy cafeterias.

"Security guards greet them like they do the president of the company," Hogan said. "It adds fuel to their fire to do well academically."

Marlene Chapa hugs her son Robert Placensia at the Cathedral of Our Lady of Angels after his Verbum Dei High School graduation ceremony on June 6. More photos

Ricardo got on a Verbum Dei bus headed toward the skyline of downtown Los Angeles. With his back to the bus window, he avoided looking at the auto repair shops, weathered storefronts and empty lots that dot the landscape along Central Avenue in Watts.

Forty minutes later, he was dropped off downtown. He was no longer the timid kid who walked into the wrong skyscraper three years ago, when he was first assigned to work in the copy center at Locke Lord. On this, his last day on the job, he waltzed into the building, using his keycard to gain access to the elevators.

"You must be happy," a colleague said as he entered the workroom. "Real work is coming your way."

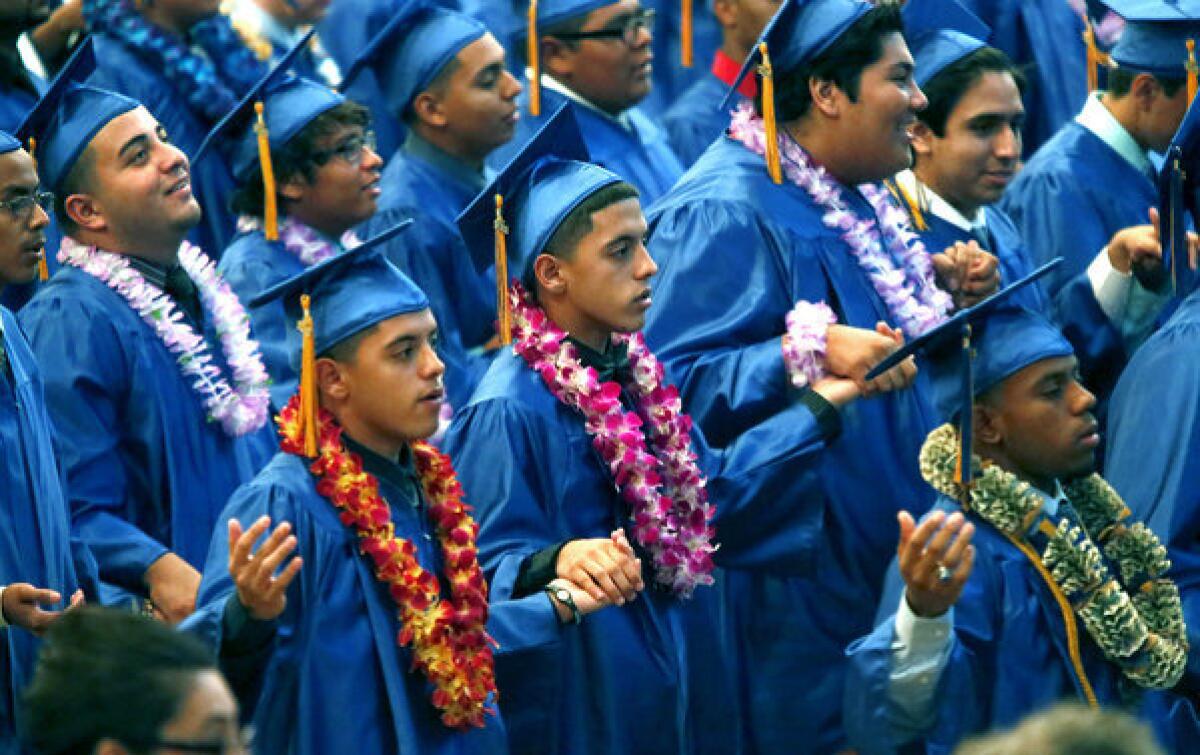

Weeks later, Ricardo and Roberto took the stage at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels wearing blue caps and gowns and brightly colored leis — one orange and yellow, one pink and white.

After the graduation ceremony, Chapa squeezed Roberto's smiling face and drew his forehead to hers. She let out a deep breath and allowed the tears to flow.

Later, inside their Watts home, Chapa reflected on the pride she feels for her sons.

"Happy," she said as she covered her face. "For me — everything, because I raised them alone."

Ricardo leaned into his mother.

"I see I made her proud," he said. "That's the one thing I've wanted to do."

Follow Angel Jennings(@LATangel) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads (@latgreatreads) on Twitter

More great reads

Alaska offers hope for a stricken son

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.