UCLA students dig into the physics of food

A class at UCLA teaches all about the science behind what makes lettuce crispy and coffee bitter, and what makes food taste good or not.

- Share via

The three undergrads looked warily at the pulverized apples in their bowl.

The would-be pastry chefs had planned to drop dollops of the mixture into a chemical bath, creating fruity spheres with a filmy skin and an oozing interior. Their early attempts left a lot to be desired. The apple mush was bland, like baby food. The finished globules were teardrop-shaped rather than round. And they were chewy, like aging Jell-O.

"It needs sugar," Amirari Diego said, with a sigh.

Diego and his two buddies, Stephen Phan and Kevin Yang, were playing with their food for the sake of science — and their transcripts.

They're students in Physiological Sciences 7 (that would be Science & Food to you and me), a class at UCLA that teaches all about the physics that make lettuce crispy, meat chewy and dough springy; the molecules that make coffee bitter, and carrots sweet.

Students get to eat ants with Brazilian chef Alex Atala and watch "Top Chef" champ Michael Voltaggio make a complicated beef dish. They attend lectures by culinary luminaries such as Chez Panisse owner Alice Waters and Momofuku Milk Bar founder Christina Tosi.

At the end of the semester, 25% of their grade will hinge on what might be the world's first "scientific bake-off" — a glitzy competition to create an American classic: apple pie.

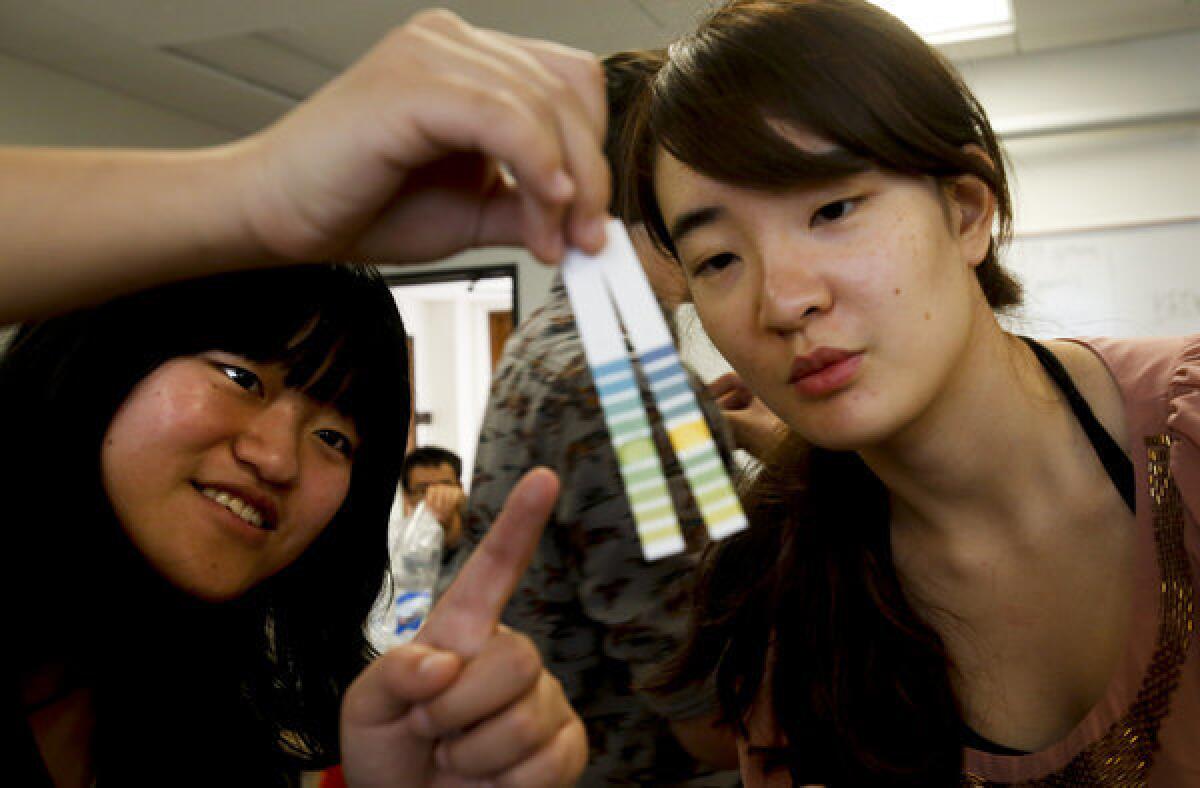

Before the class is over, students will assess the "structural stability" of their crusts, calculating pastry density using kitchen scales. They'll dip strips of litmus paper into pie fillings to measure pH and gauge whether Granny Smith apples' acidity makes them better or worse in a pie, or how acid affects the way custards congeal in a filling. They'll use math equations that include pi.

And they'll learn whether good science makes good pies.

"I'm a science major, and this has been really hard," said Neil Brinckerhoff, a human biology and society student. "It's a lot of different concepts in one class."

Science & Food students busy at work in a laboratory. (Anne Cusack / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Professor Amy Rowat, a 37-year-old Canadian biophysicist whose reddish curls and penchant for boots and printed T-shirts make her look like a student herself, co-developed the idea for Science & Food about three years ago, during a teaching stint at Harvard University. Carbohydrates, fats and proteins, Rowat came to realize, were nifty vehicles for explaining a lot of scientific concepts.

"Food is something students can experiment with directly," she said. "They have experience with it."

So Rowat, a self-described "intuitive cook" who had been experimenting in the kitchen since she was a toddler, designed a course that used food to explain physical science. In class, she explained why cooking amounted to "altering the interactions between molecules," and how temperature, acidity, salt content and physical manipulation of ingredients all played a role in making food safe and delicious to eat.

Rowat added the bake-off this year because she wanted to get students thinking about the scientific method: the painstaking process scientists use to understand the world around them.

There was catastrophic failure at all levels."— student Carter Varnum

During a May 1 lecture called "Apple Pie 101," she donned a bright orange apron — the word "gastroscientist" emblazoned across the front — and talked while making a pie. Rowat explained how fats in dough can interrupt the formation of networks of the protein known as gluten, influencing whether (or not) a crust winds up pleasingly flaky.

Students might experiment with their crust, she said, or with their filling.

"You have complete creative freedom," she told the class. "But fundamentally you want to ask a scientific question you can address through an experiment."

The following Thursday, the class showed up for a laboratory session with apples, butter, flour and other materials in hand. Some forgot their pie tins. Others weren't entirely sure how to operate ovens or food processors. No one remembered oven mitts.

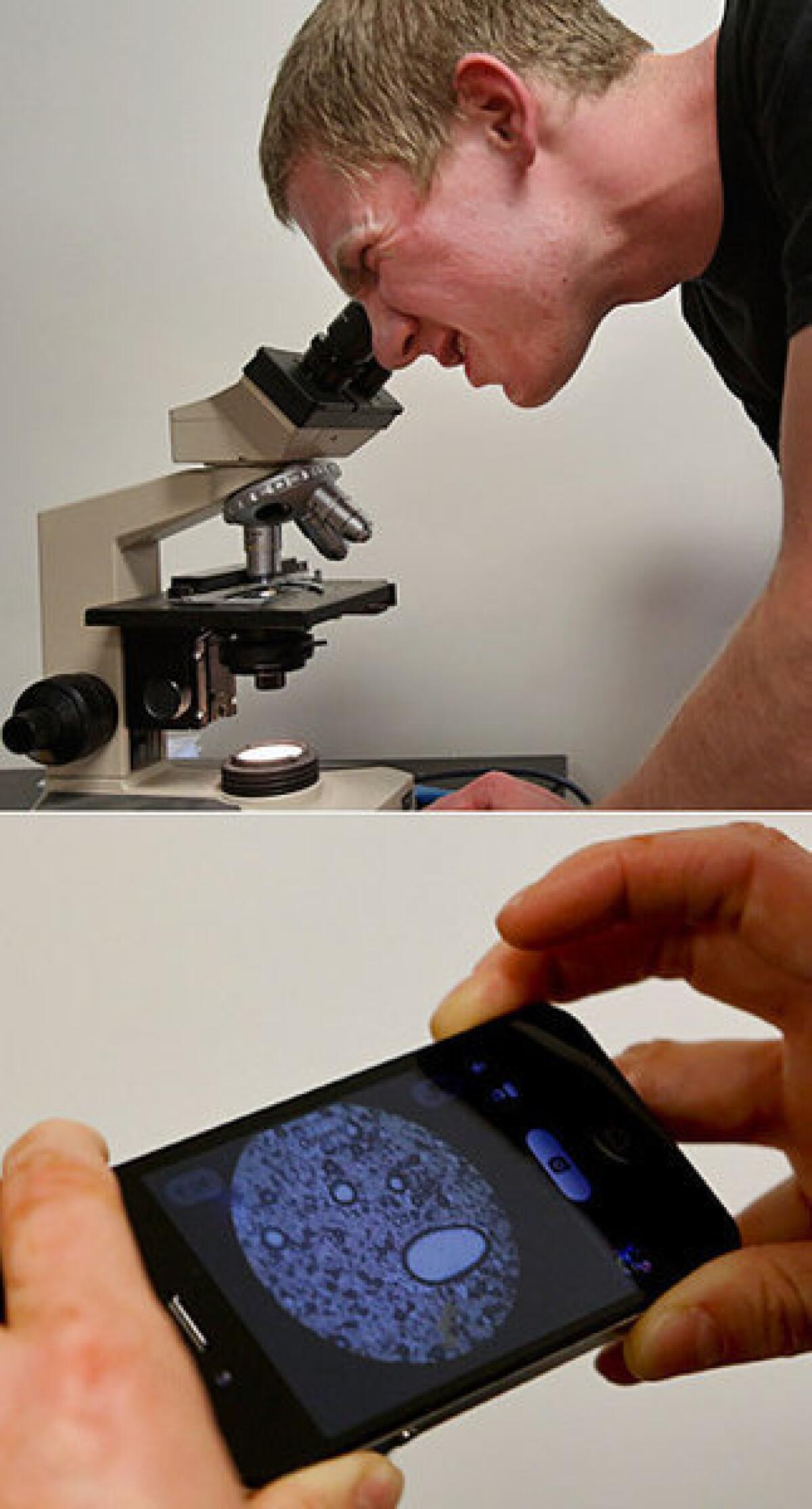

Caleb Turner looks at egg white bubbles in a peanut butter mousse through a microscope, and a shot of the bubbles is taken on a student's mobile phone. (Anne Cusack / Los Angeles Times) More photos

In two-hour shifts, the students baked and pondered their pies, collecting data where they could. Some teams tried out different fats in their crust. Others, in fine collegiate form, tested how adding various types of alcohol to the recipe — rum, bourbon, vodka — affected flakiness and color.

Some students went out on a limb. Senior computer science major Caleb Turner and first-year theater major Elan Kramer made a Frozen Peanut Butter Cloud Apple Pie, meant to examine how egg whites worked as a surfactant, stabilizing bubbles in a fluffy peanut butter mousse.

Turner slipped a glass slide with a smear of peanut butter filling onto a microscope sitting next to a bank of toaster ovens. At first, he couldn't see anything. Rowat walked over and showed him how to focus. Gradually, tiny air bubbles came into view.

"Oh, so cool," he gasped.

Across the room, Diego, Phan and Yang were working on their apple spheres. Their project was designed to explore diffusion and gelation: how a solution of calcium chloride can penetrate the apple blobs, which are mixed with a chemical called sodium alginate. The thicker the skin on the spheres, the farther the calcium chloride has diffused into the apple, reacting to create a gel.

Their "juice balls" were gooey, they suspected, because the diffusion was occurring too rapidly. Teaching assistant Andy Trang reminded them about an equation the class had tackled, Fick's law, which indicated that lowering the concentration of calcium chloride in the bath would slow the congealing process, resulting in a thinner skin and the desired burst-in-your-mouth effect.

"Ahhhhhh," Phan said, pleased. His teammates scrambled to the sink to dilute their bath and, they hypothesized, make a yummier dessert.

The following week, Voltaggio came in to deliver the lecture "Meet Meat."

The "Top Chef" winner, who owns the Ink and Ink Sack restaurants in West Hollywood, shyly told the students he wasn't a scientist and confessed that he felt "nervous to be speaking before the future scientists in our field."

He talked about the process of trial and error that cooking entails. "We do research, just like you," he told the class.

Students check the pH of rum they are using in their crust. (Anne Cusack / Los Angeles Times) More photos

One student raised his hand.

"Do you ever have experiments that are not salvageable?" he asked.

Voltaggio's answer — yes — might have been a comfort to the students on Sunday, when they gathered in a campus dining hall, donned hair nets and gloves, and scrambled to prepare for the bake-off's tasting event that day. More than 400 people, many of them strangers, would line up to try out the class' wares and view posters detailing their research.

The students with the best-tasting pies would win their choice of a small appliance, and bragging rights. Many seemed worried.

"There was catastrophic failure at all levels," first-year student Carter Varnum said of his team's first effort. Neither he nor his teammate, freshman Steven Hilz, had ever made a pie before. They had hoped to use scientific data to determine which apples would make the most desirable filling. But their experiments hadn't quite gone as they'd hoped. For the purpose of the bake-off, they ended up working with Fuji apples after unscientifically trying some and deciding that they tasted the best.

Two teams independently discovered that substituting avocado for the butter in a pie crust was "disgusting" — perhaps, the data suggested, because the relatively high water content in the fruit promoted the formation of gooey gluten networks.

But there were triumphs too.

Turner and Kramer analyzed the air bubbles in their peanut butter filling and showed, using graphs, why their recipe had optimized airiness in the mousse. Their pie was sweet and cold and nutty, both smooth and crunchy, and topped with a generous layer of whipped cream. The audience gobbled it up and voted it their favorite.

Christina Tosi, chef, owner, and founder of Momofuku Milk Bar, left, and Zoe Nathan, the co-owner of several Los Angeles restaurants, right, judge students' pies. (Christina House / For The Times) More photos

Also victorious were Diego, Phan and Yang, whose deconstructed apple pie spheres, topped with ground-up bits of graham cracker crust, took the best-tasting pie prize, wowing an "Iron Chef"-style panel that included Milk Bar's Tosi, Huckleberry owner and baker Zoe Nathan, Times food critic Jonathan Gold and Evan Kleiman, host of KCRW's "Good Food."

For the recipe's final incarnation, after doing a whole lot of math, the team figured out how to make dumplings that popped pleasingly in the mouth, with a sweet and spicy flavor and just the right amount of crunch.

Rowat said the creation successfully illustrated the science of diffusion. The judges called it just the right balance of calculation and art, and praised the team for using science to improve the taste of their dessert.

Phan said he just hoped he'd get a decent grade.

Follow @LATerynbrown on Twitter

More great reads

Cannes: Kickstarter kids make an unlikely trip

It cost us more money to come to Cannes than to make this movie.